Student with dyslexia adjusts to teachers’ different methods

By Lexi Muir

<[email protected]>

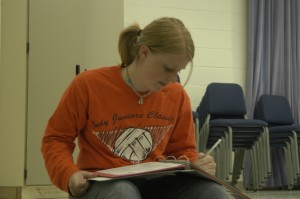

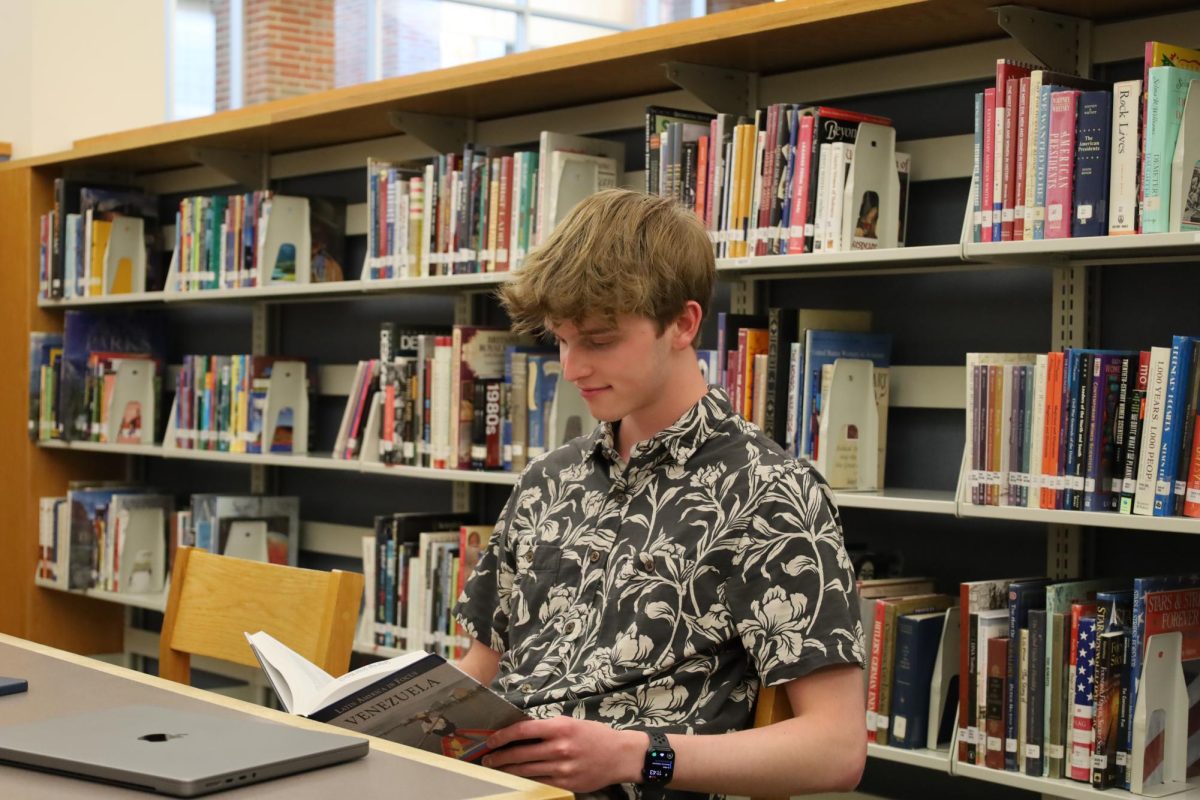

As senior Avery Hollenback stares at the questions on her Algebra II test, she reads over each question, as well as her answers, four to five times. It’s not because she doesn’t know the answer, or even because she is double-checking to make sure she answered correctly. She is checking to make sure she is reading and understanding the question correctly and seeing the numbers as they really are. Avery, unlike most of her classmates, is dyslexic and deals with problems like this every day.

“I have mild dyslexia,” she said. “I mix up numbers and have to read over questions over and over again. I have problems with comprehension. Sometimes I even put the wrong answer without ever knowing.”

According to Rosie Hickle, Executive Director of the Dyslexia Institute of Indiana, there are varying degrees of dyslexia from very mild learning differences to very severe differences in how they process information in the areas of their brain dedicated to learning to read.

Hickle said that it is a misconception to think that people with dyslexia just read backwards or just reverse their letters.

“It is much more complex than that,” she said via e-mail. “It can show up in how they process what is being said to them, what they read, how they spell or how the brain works from when information is brought in through their eyes and ears and what comes back out on paper. In other words, it is very complex and is about how a person processes information.”

Avery said that her degree of dyslexia affects her comprehension more than it affects her ability to see letters and numbers correctly. She said that she will mix them up every now and then, but the real problem exists in her comprehension. Sometimes, Avery said that if she doesn’t know the answer to the question or can’t understand the question, she doesn’t know whether it is the dyslexia at fault or her knowledge of the subject.

“During tests, when I can’t comprehend something or I can’t figure out the answer, I don’t know if it is because of the dyslexia or because I just didn’t study hard enough,” she said.

According to Julie Hollenback, Avery’s mother, the first sign that Avery was dyslexic was spelling.

“She just couldn’t spell,” Mrs. Hollenback said. “She was very stubborn about it and just could not spell simple words correctly.”

After being tested and diagnosed with dyslexia, Mrs. Hollenback said that Avery was pretty much on her own.

“She just works harder,” said Mrs. Hollenback. “She continues to go back over stuff and learn it over and over again. In order to deal with it, she has to work harder than the average student, period.”

According to Hickle, dyslexics process information differently and because of that, they need to be taught using a multi-sensory approach.

“Information needs to be given to them through three sensory channels at the same time. (visual, auditory, tactile/kinesthetic),” she said. “The ultimate goal (for teaching dyslexics) is to have timely and appropriate teaching strategies in the classroom so that students can overcome their challenges of learning to read and to help them accept that they learn differently.”

Avery and Mrs. Hollenback both said that the hardest challenge for Avery is working with her teachers.

“They don’t give much room for mistakes,” Avery said.

Hickle said that the hardest part for

most students is accepting that you are a smart person. It is very easy for them to feel stupid and many times the world around them reinforces that.

Avery stays away from telling her teachers about her dyslexia because she doesn’t want them to think she is just trying to get out of doing work or get off easily.

Mrs. Hollenback said that she thinks that even if the teachers did know, they would not show much concern or give much help anyway.

“(Teachers) are dealing with somebody who is socially adept and able to keep up but just isn’t an AP kid and isn’t an A plus student,” she said. “Teachers at Carmel don’t care about anything but that. Some will work with a student but it’s up to her to challenge the teacher to work with her.”

As far as feeling disabled goes, Avery said that being dyslexic definitely brings about a challenge for school, but she does not consider herself to have a major problem.

“Everyone has their own problems,” she said. “I’m not disadvantaged. I don’t have anything compared to what some people go through every day.

I don’t see dyslexia as a big deal. It’s a big deal for school, but then I look at everything I have going for me. I consider it pretty low down on my list of problems.”

Mrs. Hollenback said, “She can achieve anything she wants to do. There is patience involved, but she can do it. Not every test defines a child, and that holds true to people like Avery who work hard.”

—

FACTS ABOUT DYSLEXIA

- Research suggests that about 17 percent of the population has dyslexia.

- Because the source of dyslexia lies in the brain, children do not outgrow dyslexia.

- An equal number of girls and boys are dyslexic.

- Children with dyslexia have strong listening vocabularies and understand text when it is read aloud to them.

- They have difficulty recognizing common “sight words,” or frequently occurring words that most readers recognize instantly. Examples of sight words are “the” and “in.”

PBS.ORG / SOURCE

Story updated on 10.8.08

![British royalty are American celebrities [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Screenshot-2024-03-24-1.44.57-PM.png)

![Review: “The Iron Claw” cannot get enough praise [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/unnamed.png)

![Review: “The Bear” sets an unbelievably high bar for future comedy shows [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/unnamed.png)

![Review: “Mysterious Lotus Casebook” is an amazing historical Chinese drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/0.webp)

![Thea Bendaly on her Instagram-run crochet shop [Biz Buzz]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IMG_0165-1200x838.jpg)

![Review: Sally Rooney’s “Normal People,” is the best book to read when you are in a time of change [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/20047217-low_res-normal-people.webp)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: When I Fly Towards You, cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie, departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: Hidden Love is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: Heartstopper is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)

![Review: Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie, departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster-221x300.jpg)

![Review: Next in Fashion season two survives changes, becomes a valuable pop culture artifact [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Screen-Shot-2023-03-09-at-11.05.05-AM-300x214.png)

![Review: Is The Stormlight Archive worth it? [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/unnamed-1-184x300.png)