Alone in the crowd?

As many students do not receive proper mental health services, CHS discusses importance of mental health awareness

DON’T JUDGE A BOOK BY ITS COVER:

Senior Kelsey Irwin poses for a photo with her journal, in which she writes her emotions on paper without resorting to destructive behavior. English had always been Irwin’s favorite class, but due to her mental disorders, even her teacher noticed she was not doing her work in class. “In my case, it was pretty noticeable, but there’s a lot of people where it’s not noticeable. Their grades might not change, and their outward behavior might not change, but inside they could just be going through so much, and you just wouldn’t know,” she said.

At 13, senior Kelsey Irwin said she lost her motivation to keep going. She started to quit everything she had loved doing: theater, dance, choir, hockey, volleyball, soccer and more—the list goes on. It was at this point in her life when she was close to giving up. She almost let her “inner demons”—intrusive thoughts always at the back of her mind—get the best of her. It was almost too late.

“It was like there was a giant cloud inside of my brain. It was covering my emotions to the point where I just couldn’t be happy. I couldn’t appreciate the small things that life actually has to offer, and I was just forgetting my own world. I was just in a really dark, terrifying place, and I was lost.”

For weeks, Irwin said she was on a downward spiral. Her appearance started to suffer. She stopped taking care of herself. Her grades dropped. Many days, she wouldn’t come out of her room or eat.

THREE MEALS A DAY KEEPS THE DOCTOR AWAY:

Senior Kelsey Irwin eats a bag of chips during lunch. She said she struggled with not only a major depressive disorder but also an eating disorder, which caused her to lost 30 pounds in two months.

“Why even try anymore?” she thought.

At first, she was able to mask her struggles.

“I acted like anyone else would,” she said. “I talked to my friends. I would eat with them, engage in conversations without bringing up what I was going through. Even when my friends would bring up problems with their lives, I would be the rock for them and be the person they could rely on even though there were things I wanted to say, but I felt like I couldn’t because I didn’t want to be a burden, so I didn’t say anything to them for a long time.”

She said she felt like she either had no one to talk to or had no one who would understand. She was isolated.

Irwin suffers from major depressive disorder and general anxiety disorder, but she said she waited several years before getting the treatment she needed.

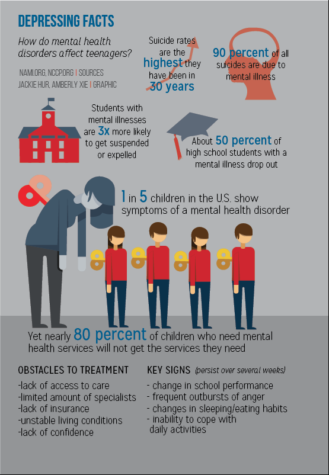

She is not alone. According to a 2016 UCLA Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences study, one in five children and adolescents in the United States show signs or symptoms of a mental illnesses in any given year; however, only 20 percent of them receive the mental health services they need. At Carmel, that would statistically account to over 1,000 students who struggle with mental health issues with around 800 of them not getting the support they need. Jackie Hur, Amberly Xie

To address some of these issues, CHS is holding a Culture of Care week from Feb. 26 to March 2. During the week, there will be several daily activities including students, parents, staff and the community. According to director of counseling Rachel Cole, this week is part of a larger initiative to bring more attention to mental health at the school. She said though the counseling department is initially behind leading this move, she eventually wants everyone to take part, and going forward, the school will be putting more of an effort to develop this “culture of care” through creating a three-year-plan and putting together a “steering committee” of many different individuals throughout the school.

Cole said the reason behind having this week is that the counseling department has seen an upward trend in the past few years of students asking to see a counselor for stress, anxiety, sadness or something else.

Social worker Kate Kneifel said currently, there is somewhat of a stigma associated with reaching out for mental health support—an issue the school hopes to address through its Culture of Care initiative. “(Those who struggle with mental health issues) think they should be able to deal with it in on their own or that people are going to judge them,” Kneifel said. “But it’s okay to seek help.”

For her part, Irwin said she personally held back from getting that help for a long time.

“I was just scared,” she said. “I eventually kind of figured out what it might be, and I didn’t want to accept it, and I didn’t want to be on medication because I knew that if I explained how I truly felt; that’s probably what it would come down to. Even though that was the help I needed, I just didn’t want it.”

However, Irwin said her mother eventually convinced her to start treatment.

At first, she said the process of recovery was quite discouraging. Everything was changing around her. Her friends started asking what was wrong—causing her to enter a cycle of increasing anxiety. She was in denial. She couldn’t hide it anymore. She wanted to give up.

Once again, she began to think: “Why try?”

But soon enough, things started to look up.“I want to live a long life,” she realized. “I don’t want to let my inner demons get the best of me.”

“The clouds now are slowly parting, and there’s some light of hope shining in now, whereas before, there was nothing… Recovery is a long, grueling process, but slowly but surely, it will get better.”

Kneifel said Irwin’s case is actually not uncommon. In fact, she said, many students will come into her office, sit on the chair leaning against the wall and tell her that they feel like they are the only ones who are dealing with a certain issue.

“They look around, and everybody’s got it together. They’re achieving. They’re looking good. They’re having fun. Their social media’s awesome,” she said. “What I say to them is that I have a lot of people who sit in that chair and say the same thing. We all have our struggles at different times. No one goes through life without some struggle and you’re not alone in that.”

Irwin said, “Although I have given up at certain points, I’m still going today, and I plan on pursuing college and higher education because I know that in the end, it’ll be worth a lot… It’s just having hope.”