Your donation will support the student journalists of Carmel High School - IN. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

No Weigh To Live: Anorexia has highest mortality rate of all psychiatric illnesses; CHS students struggle to combat its effects

January 24, 2019

Junior Sara Stockholm knew something was seriously wrong the second she stood up and felt like she was about to faint. It was the end of her freshman year, and she hadn’t exercised or worked out at all during the day. Instead, she knew she had another, much more serious and deep-rooted problem. For the past few months, she had limited her dietary intake to 800 or even 300 calories a day. Her meals consisted of nothing at all, or at most, an apple and a cup of tea, while her days consisted of a fanatical obsession with calorie tracking.

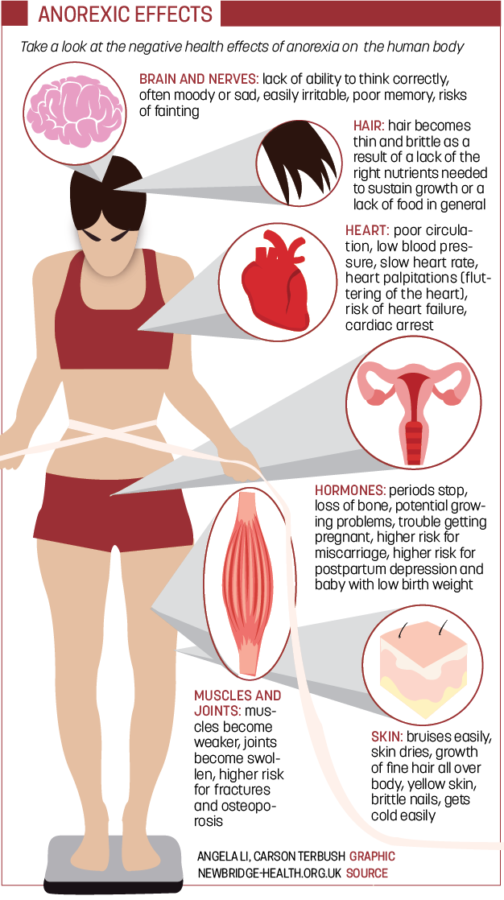

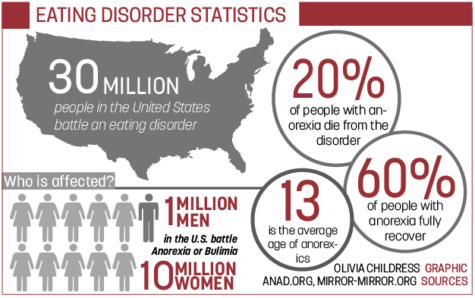

Stockholm is one of the 1.5 million females in the United States suffering from anorexia nervosa, an eating disorder categorized by a compulsive obsession with weight, size and low self-esteem. She said that for her, the disease surfaced freshman year as a result of depression, but it can surface any time, most commonly during puberty. A January 2018 study by U.S. News and World Report found that eating disorders are the deadliest of all mental illnesses, specifically with adolescents at the greatest risk. Furthermore, for females between 15 and 24 years of age, the death rate associated with anorexia is 12 times higher than all other causes of death.“That feeling was draining and it’s still draining to think about today, especially when that feeling resurfaces. It was draining, emotionally and physically and mentally and everything. I got referred to a therapist after I was basically found in a pile of my own blood from my own self-harm,” Stockholm said.

Ashlee Edgerton, licensed therapist and certified eating disorder specialist at Indiana Health Group in Carmel, said while eating disorders affect people of all ages, they are more common in adolescents.

“It’s definitely more common in adolescents and people that are college-age, but it can affect anyone. In my practice, I’ve seen (anorexia affect someone) as young as 5 (years old), and eating disorders don’t tend to go away like some other issues can with age. If an eating disorder is not treated, it will continue throughout the person’s lifetime, even sometimes in pockets,” she said. “(There are) people in their 80s with an eating disorder at times, because if they never sought treatment when they were younger; it’s not the kind of thing that will go away with time.”

Moreover, Edgerton said eating disorders are more common in Westernized cultures and affluent communities, meaning places like Carmel and Zionsville have higher rates of eating disorders.

Stockholm said she currently attends therapy and sees a psychiatrist. She said those two resources have helped her tremendously, but her eating disorder still impacts her.

“It’s always an issue there because it’s always in the back of your mind. Even if it’s not a very prevalent issue in my life right now, it’s still definitely there. Small things, like you eat three meals a day plus people eat snacks throughout the day, but constantly having that thought about ‘You don’t need food, you’re fine,’ in the back of your mind is just like a lot,” she said. “Honestly, what helped the most was probably just support from my friends: them shoving food in my face and being like, ‘You need to eat.’”

According to Edgerton, there are three types of professionals that someone with an eating disorder needs to see: a therapist, a dietitian and a doctor, all of whom must specialize in eating disorders. While there are many different levels of care, no matter the level, the patient must have those three professionals.

“If someone is not critically sick or they haven’t been struggling with eating disorders for very long, then they would go to an outpatient therapist, which is what I do. They do about an hour of therapy a week, maybe an hour of nutritional counseling a week and then maybe see their doctor once a month. But if the eating disorder is more severe, there’s programs called IOP, intensive outpatient programs. That’s where they’ll do a combination of individual therapy and group therapy,” Edgerton said. “Sometimes they’ll even do some sort of activity therapy as a group, like yoga and body movement therapy, or an assistant meal group where someone is monitoring them and helping them finish a meal. Then, finally, there are programs that are residential, and that’s the highest level of care where they would go and live in a unit specifically for eating disorders for a month or more.”

Therapy sessions for adolescents specifically are unique because they emphasize parent involvement, with over 25 percent of a session consisting of time with both the patient and his or her parents. Treatments for adolescents also differ from adults because sometimes, they need permission slips to eat snacks in school, have different FDA-approved medications and usually work on relationships with parents during the sessions.

To Edgerton, one of the most important factors is catching the disorder early. She said, “If I could think of one thing to share. It would be to seek help as early as possible because the farther an eating disorder gets or how much time goes on with the struggling with an eating disorder, the longer the treatment gets to me. Sometimes, I have parents call in and ask about bringing their child in for self-esteem issues, and there aren’t any eating issues yet. I always recommend that they do, just because eating disorders are a lot (to deal with). The rates of them are a lot higher now just because of the media teenagers are exposed to.”

THEATER TIME: Junior Sara Stockholm and her friends do theatre improvisation during SRT. Stockholm said support from her friends has really helped her recovery process.

Stockholm said that now, as an advocate for eating disorder awareness, she agrees that seeking treatment is one of the most important steps. She said, “People need support for this thing. It’s not really something you can do by yourself; you definitely need someone to help you.

“I don’t want to sound cheesy, but (if you are struggling with an eating disorder) reach out to one of your friends or something because I know it’s scary to talk to an adult, and be like, ‘Hey, I’m doing this.’ Instead, talk to one of your friends and be like, ‘Hey, I don’t think this is a healthy habit that I had, can you help me with this?’”

One of the biggest complications among those that suffer from eating disorders results from secrecy and hiding. Edgerton said she believes it’s not always that the patient is lying or trying to hide from others, but is denying his or her disorder to themselves.

She said, “A lot of times they go unnoticed, so if you know your friend has one, if you think your sister has one, tell your parents, tell your guidance counselor, because you don’t want that to go on for them. Eating disorders are the deadliest of the mental health issues. It really is a life-death issue, so if someone finds out they have an eating disorder, they need help.”

Yasmine Pehlivan, vice president of the Mental Health Awareness club and junior, said anorexia, like all mental illnesses, is not as recognized as it should be. She said, “Most people don’t really know or pay attention to mental illnesses, so we just try to reinforce a positive attitude at school.”

Last year, the club wrote positive messages on notes and displayed them around the school. Pehlivan said this was in an effort to boost students’ self-confidence, and make them feel like someone cared about them

On her part, Edgerton said she thinks awareness for eating disorders has improved, but there is still a long way to go.

“Karen Carpenter, a singer, she actually died from an eating disorder, from a heart complication, which is actually one of the biggest risks for anorexia. When that happened (in 1983), no one knew what an eating disorder was. I would say we’ve come a long way since then, but I would definitely want it to improve even more, just to where people wouldn’t be embarrassed to talk about it,” Edgerton said. “For a lot of my clients, if they have to leave school or early or leave for like a lunch period, we spend time talking about what they’re going to tell their friends and they’re embarrassed if people are going to know, and I think that’s really sad. No one gets embarrassed going to the dentist in the middle of the school day, and an eating disorder is not something you chose to have, so no one should be embarrassed about it.”

Stockholm said as someone that has and is still suffering from anorexia, she has found a lot of gaps in other people’s knowledge or perception of eating disorders. She said, “I want people to acknowledge that (eating disorders) are a thing and people aren’t just attention-seeking. I want people to acknowledge that guys can have them too, and it’s actually an issue; it’s not just a cute little mental health thing. Some people romanticize things like this and it’s not, it’s not cute. It’s a lot more serious than you think. It’s not just a diet that people go on, like ‘I’m just going to go on a diet and exercise to lose a little weight.’ It’s obsessive, where you’re constantly looking at calories and logging calories for things.”

Stockholm said she wants to emphasize that healing is not linear. She said, “I’m not cured. I’m not better. This isn’t something that doesn’t affect me anymore. This still affects me constantly, it’s still something I have to deal with every single day.”