Your donation will support the student journalists of Carmel High School - IN. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

With CHS’s large, competitive environment, students assess how pressures foster imposter syndrome

November 21, 2020

This past summer, sophomore Celia Watson moved to Carmel two weeks before the start of school with only a suitcase full of clothes and her guitar in her hand. Watson moved here from São Paulo, Brazil, but has lived in Cincinnati, Germany, Italy and Belgium, too.

“Moving is a part of who I am,” Watson said. But Watson’s scattered moves across the world point to a bigger unintended consequence.

“Strange feelings of internalized doubt hit me really hard with my move to Carmel,” Watson said. “I’m coming from a school where the entire high school was 120 people total. The jump to Carmel has been huge, and of course there are many negative experiences along with that. I’m not sure if I belong here all the time.”

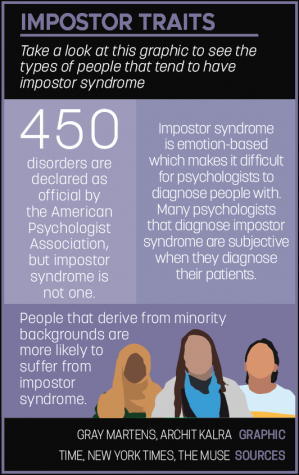

Watson’s feelings are just a small example of a larger phenomenon: impostor syndrome. As particularly demonstrated in the popular video game “Among Us”, this role of being an “imposter” is ever more present not only in the game, but also in life. First introduced as a concept in the 1970s by psychologists Suzanne Imes and Pauline Rose Clance, impostor syndrome is defined as a phenomenon in which people are unable to internalize and accept success. Rather, those who experience impostor syndrome often attribute success or happiness to luck instead of their own ability, and fear others will suspect them to be a “fraud.”

A study conducted in 2011 by Dr. Jaruwan Sakulku found that as much as 70% of the total population has experienced some feelings of being an impostor at some point in their life. Similarly, a study commissioned by a career development agency “Amazing If” found that younger generations are more vulnerable to impostor syndrome as a third of people from younger generations, particularly high school and college students, regularly experience it.

According to therapist Laura Snyder, this syndrome is largely caused because of the natural competitive tendencies humans have, explaining why schools in particular are breeding grounds for such a mindset.

“Impostor syndrome is the fear that we are falling short and others aren’t, so anything that puts you in that comparative mindset is the driving factor,” Snyder said. “That’s why it’s especially common among students because easy access to such a large demographic that often contains so many people who excel makes it really easy to compare and fall into those thoughts.”

Freshman Angelina Tan said she agrees with Snyder’s explanation based on her own observations and previous experiences.

“I think Carmel has always prided itself on being the best, but that pressure extends to its student body.” Tan said, “Academically, grades and GPA have often manifested themselves into being measures of self-worth, and that can be really damaging for mental health and stress.”

Watson said she also agrees with this explanation, as she has noticed differences in schooling environments with her experience in Brazil.

“In Brazil, sports fall second to nearly everything. They’re something to do on a day off, or to catch up with friends. This differs significantly from the American point of view, where the ideology is that if you are not winning, it isn’t fun,” Watson said. “I joined volleyball my freshman year in Brazil and ended up adoring it and actually being one of the starters on the team. I know for a fact that this couldn’t have happened at Carmel High School, and I think that’s an issue. Hustle culture is good in small doses, as are many other things. Too little, and you don’t get pushed. Too much, and you’re losing sleep and using unhealthy ways to overcorrect and cope.”

This consensus would explain why both Tan and Watson say they are subject to impostor syndrome. For Tan, she said she participates in many school activities and classes that are particularly susceptible to competitive environments that often induce feelings of impostor syndrome, including AP Calculus BC, AP Computer Science and debate, all of which can take a large toll on her well being.

“I’ll catch myself having not eaten an entire day, not slept for 36 hours, and just feeling exhausted more often than I’d like to admit,” Tan said. “It’s easy to say that I’ll just work harder, be more proactive and efficient, but it’s so much harder to execute those words. The external pressures have ignited internal expectations of perfectionism, and when I don’t meet those external or internal standards, I can’t help but feel guilty, disappointed and useless.”

Similarly, junior Krish Jayarapu said the competitive atmosphere and unwritten hierarchy at Carmel can catalyze feelings of impostor syndrome. Jayarapu said during his first two years of high school, he tried to take as many AP and STEM classes as possible to elevate himself. But academically challenging himself didn’t always lead to positive results mentally.

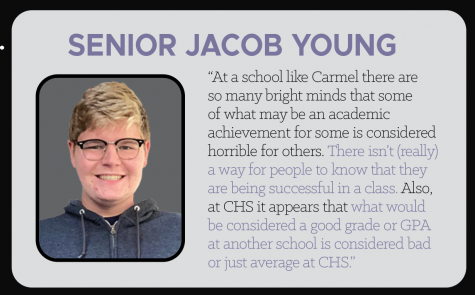

“I doubted myself and completely minimized the amount of work that went into getting into such a position. At Carmel, there will always be someone that is better than you in some way or form,” Jayarapu said. “By human nature, we tend to compare ourselves to those who are better and put ourselves down.”

Snyder says she agrees with Jayarapu. In fact, Snyder says it is more unlikely to have never experienced impostor syndrome than it is to have experienced it.

“As quoted by (research professor) Brené Brown, the only people who don’t feel shame are sociopaths,” Snyder said. “Therefore, if you have any sort of emotions, you’re going to ask yourself, ‘Am I good enough?’ And it’s hard to minimize the issue as a whole because you’re just surrounded by it; it’s particularly deeply rooted in America’s culture. We’re founded by this idea that you should pull yourself up by your bootstraps and you are responsible for your own success. So people often think, ‘I have to be responsible for this and if I fail it’s my fault.’”

Tan said she thinks one of the first steps to combating the impostor phenomenon is by being honest about it in the first place.

“I don’t think mental health is talked about enough,” Tan said. “I know that (because) in the Asian community it’s treated like a taboo, or something to be ashamed of, but I think we really need to start addressing it head on if we truly care for the well-being of the people in this school.”

While Tan commended the school for taking initiative to help resolve the problem, whether it be by having awareness weeks or emphasizing the services offered, she said she thinks more action is needed.

“The grading system treats students like workers, and their thoughts and efforts are boiled down to a letter grade that either tells them they’re doing good or not good enough. This has been said over and over again, but school isn’t about education or learning anymore, it’s just about memorizing things better than everyone else and having that on a diploma so hopefully colleges will choose you over your peers.” Tan said. “Small steps (to address the issue) could include having ‘catch-up’ days, where every class just gives you 90 minutes to ask questions, work on your own work, tell the teachers suggestions as a class, etc.”

Although such systemic change is harder to enact, Snyder said that there are actions individuals can take to mitigate the impacts of impostor syndrome. Watson said she socializes to mitigate.

She said, “Nowadays, I’m taking more time to enjoy things even if others think it’s a waste of time. Having fun is never truly a waste of time.”

For Tan, she said she likes to set aside an hour to take a break from everything, whether it be by taking a shower, listening to music, or talking with friends.

Jayarapu takes a different approach; when he feels down, he said he uses those feelings to motivate himself to become better and stronger. Additionally, he said he finds support from others’ help to erase any feelings of impostor syndrome. For him, building communities and finding friends who motivate him has helped improve his mental health altogether.

“When others notice and compliment your position, that’s when you realize you deserve to be where you are,” Jayarapu said. “I have realized that this culture—one where we form friend groups that build each other up—will actually benefit the future and how students deal with impostor syndrome in the long run.”

In general, Snyder said coping mechanisms can manifest in many ways, but connecting with others is the most effective.

“While there’s some value in things like writing or running or anything that you consider a hobby, the biggest thing you can do is find a couple of people you can trust,” Snyder said. “After all, impostor syndrome is telling yourself ‘If people knew this about me, it wouldn’t be okay,’ so by letting those people you trust know the real you, it can really be healing,”

Additionally, Snyder said she recommends everyone to do some self-reflection in order to identify where the issue lies.

“Evaluate what you’re working towards,” Snyder said. “Ask yourself, ‘Do I actually want these things or am I just trying to look good?’ If it’s the latter, then realize that it’s not a meaningful value to base yourself on and you’re going to feel like an impostor because that’s not where you’re supposed to be. You should value this idea of ‘I may not be perfect at it, but it’s worth it for me’ versus ‘I want to get good at this because it looks good.’”

Above all, Watson said impostor syndrome and feeling insecure are not the end-all be-all—but the initial experiences can be incredibly draining.

“Impostor syndrome can take so much away from one’s real potential. Feeling like you don’t deserve what you have means you won’t push to get more and more, which is what growing and evolving as a person is all about,” Watson said. “But, you are not alone. You aren’t—it feels weird and cliche to say that, but I fully believe it’s true. These feelings, especially as teenagers, can feel overwhelming and suffocating. But knowing others feel the same way is integral to having change and making your well-being the utmost priority.”