During second period on Blue Days, the easiest thing to notice in Room C123, where freshman Gracie Coleman is in her Ceramics I class, is the whirring sound of the pug mill, which mixes up dry clay with water so students can use the clay again. From there, it’s a scene typical of a high-school art classroom; the students smooth out their work with the pots from other classes lining the walls around them, the smell of clay pervades the air, the general air of energy that accompanies students hard at work is almost tangible.

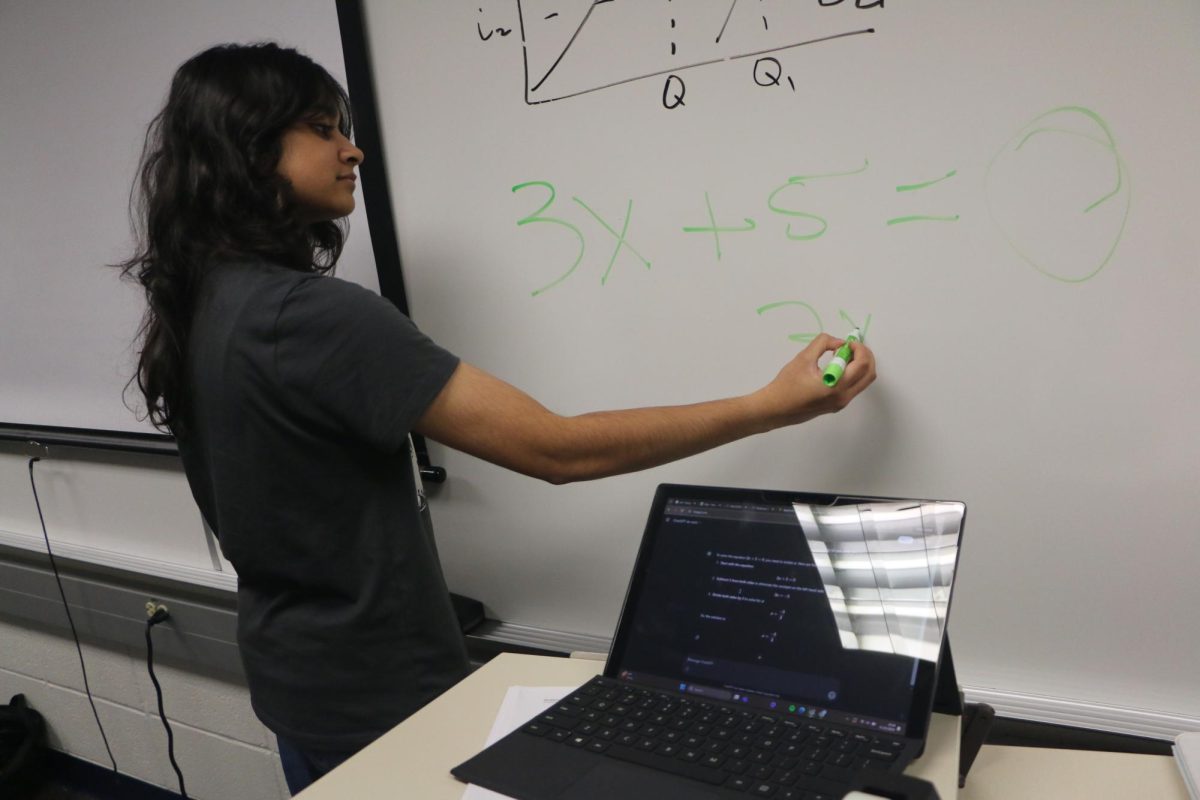

Less obvious, easy to overlook among the on-goings of the busy room, students’ papers peek out of scattered backpacks: math homework, history notes and an occasional sheet detailing class policies and expectations, almost always with special emphasis on a cheating policy that went into effect at the beginning of the school year.

While educators hoped to reduce cheating at this school by introducing a stricter academic dishonesty policy at the beginning of this school year (see Page 4 for more information), administrators and teachers also look increasingly toward a form of education not yet thoroughly explored in a traditional classroom: project- and performance-based style of classes and evaluations, which offers fresh perspective on learning methods, education and even the cheating problem.

Although in nearly all of her classes—geometry, English, world history—the new procedures will be a topic of discussion and an often mentioned rule, Coleman said she expects them to be emphasized less when she walks into her Ceramics I classroom every other day.

“It’s a lot easier to cheat on a test than to cheat on a clay pot in ceramics,” she said.

According to Coleman, the nature of product-based evaluations, which makes them more difficult for students to scam their way through, is one of many reasons for educators to focus on classes that are based on performance and projects instead of straightforward multiple-choice testing.

“Learning comes with experience, and each day, you kind of learn how to make your project better,” she said. “I just don’t think that’s what (education) is supposed to be about, just tests. I think they’re trying to make how you learn a certain way, but that’s not how most of the students learn. We all learn differently, and it shows on the tests. If they learned the wrong way, not how they prefer to learn, they’re not going to do as well.”

Coleman, who said she describes herself as a creative person but a terrible memorizer, said she thinks students having more options on evaluation type would ultimately improve the education system.

“I think it would be nice to have choices on what kind of evaluation, not just like you have to take this test, but you could write or make a presentation about what you learned to highlight the key points you learned that year,” she said.

Jennifer Bubp, art department chairperson and art teacher, said the academic dishonesty discussion is one she is currently having with her students; however, according to her, she does not expect it to be as much of an issue in art class as it is in core classes, although she said she occasionally comes across cases where students attempt to pass off other people’s work as their own.

“In that sense, I think art is unique. It’s similar to cooking, I guess. You know your mom’s cooking from your grandma’s cooking, and there’s no way to try to forge it. You can replicate a recipe, but in the end, it’s the individual cook that brings the flavors out or adds the extra spice to kind of make it their own,” she said. “With art, to try to pass off somebody else’s work as your own is kind of the same thing. Typically, we can tell right away a student’s style of working or the way that they shade or have specific techniques that are inherently theirs. Trying to pass off somebody else’s is a breach of integrity, a breach of character.”

These cases, according to Bubp, tend to be few and far between, so it is easy for her to enjoy her favorite aspect of teaching project-based classes, specifically art.

These cases, according to Bubp, tend to be few and far between, so it is easy for her to enjoy her favorite aspect of teaching project-based classes, specifically art.

“Would you rather teach somebody how to fish through a lecture, or actually take them out to the lake and teach them how to fish and let them fish? What’s going to be more memorable and more meaningful? It’s the action,” she said. “It’s the discovery that happens along the way. A lot of kids enter our art classes feeling like they’re not good artists or they can’t do it, but they realize that it’s like anything else you do. I’m a firm believer that it takes 10,000 hours to master anything, and the more you do it, the better you get. I would say it’s the discovery process along the way in the projects that they’re realizing, ‘Yes! I can do this! I’ve just never devoted enough of my focus or attention to this particular technique.’”

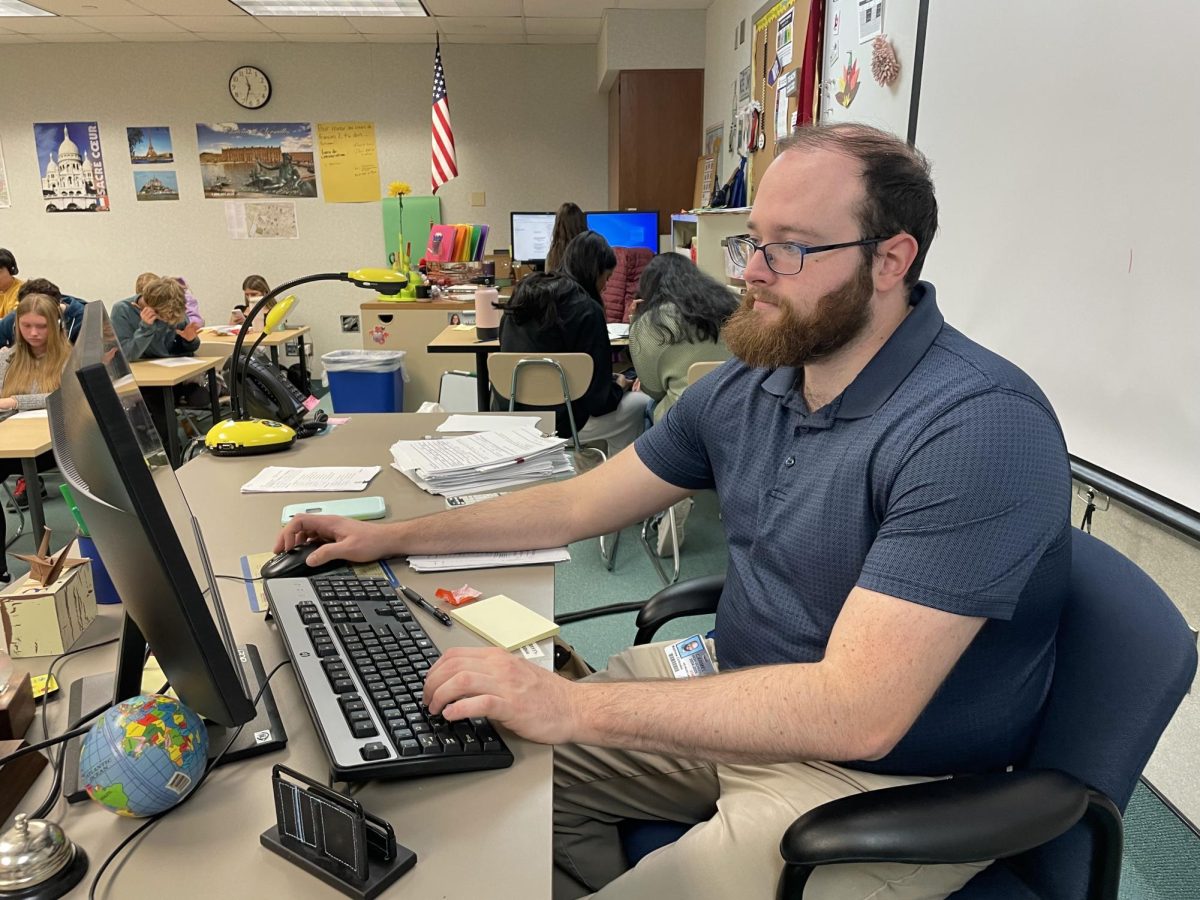

Assistant Principal Bradley Sever said he agrees that the connections and insights students are able to come to in project-based learning are a great part of teaching in that style.

“I think that what’s great about education is that each educator sort of has their own personal philosophy of education, and each teacher has their personal philosophy of what instructional methodology works best,” he said. “I’ve had a lot of positive experience with project-based learning, and I’m pretty passionate about it. I enjoy teaching that way, and I enjoy talking about it. I enjoy seeing students in a performance assessment, and I enjoy watching students grapple with a challenging, open-ended question. I enjoy seeing students be able to talk about what connections can be made with the content they’re learning in class and issues and problems that are going on in the world today. When it comes to project-based learning and students having a balanced assessment, it certainly aligns with my personal philosophy of education.”

According to Sever, an ideal style of education implements both methods of teaching and learning.

“I think that when we look at education holistically, I believe that (students) need to have experience and gain exposure to content knowledge but also gain exposure and experience in procedural knowledge, those habits of mind,” he said. “I think that sometimes, when you look at some project-based classes, the focus is a lot on procedural knowledge, but when you look at the non-content-based classes, the focus is on the content knowledge, and I think there should be a blend and combination of both with the result of providing a really authentic learning experience for students — thinking as a historian in a history class, thinking about how the past impacts the present and what we can learn from the past to solve issues and problems in the future. The same thing goes in an industrial technology class, to continue to think about ways they could incorporate formal writing and the formal writing process in addition to all of the amazing things they build and construct. I think there needs to be a balance of both.”

In any case, he said, for now, traditional multiple-choice tests will remain an important part of the education system while the state pushes standardized testing such as the End of Course Assessment (ECA) exams and colleges place emphasis on tests such as the SAT and ACT.

“I certainly think there’s a time and place for some of the traditional testing, and I think that a goal should certainly be that structures should be put in place to deter any type of cheating because traditional assessment exists,” Sever said.

Coleman said it isn’t always a bad thing.

“In some ways, (traditional testing) is effective in showing what you learned, but it depends on the student, because they all learn differently,” she said. “whereas (project-based learning) provides more creativity for the student and doesn’t have to be a specific, certain way that you have to show what you learned.”

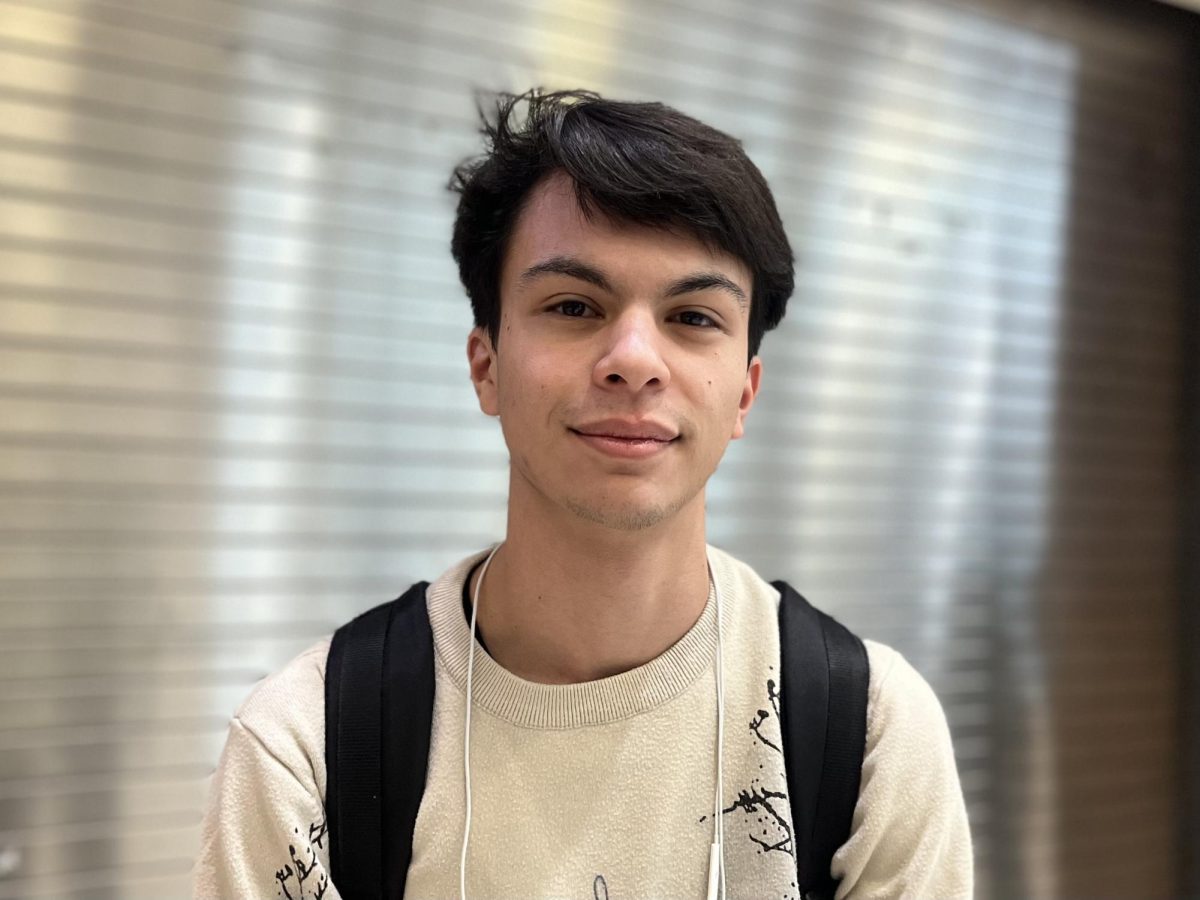

Despite its merits and possibilities its implementation poses to minimizing cheating at this school, social studies teacher Peter O’Hara said he disagrees with any notion that product-based learning is any magic solution to the issue of cheating.

“I think there’s always going to be cheating. Somebody is going to figure a way around everyone. When I was in college, I watched people cheat on all kinds of things. You can pay somebody to write you a term paper. Is that cheating? Yes. Is that multiple-choice? No,” he said. “I believe in performance-based evaluation. It’s important, but you could cheat on it. I think performance-based evaluation is good, but when it comes to cheating, cheating is not good, and you can cheat on any type of evaluation.”

In a certain aspect, Bubp said, the solution to the cheating problem is the same from class to class, be they traditional, product-based or somewhere in between: The focus, according to her, must be on learning, on self-discovery, on high-schoolers’ development of themselves as students and as people.

“I know we’re working toward an honor system for this school, and I just think it’s really important for kids to have integrity and character. It’s not just ‘What are you learning in class? What are your grades?’ but ‘What kind of student are you?’” she said. “When I was going through school, I was an A student, but I would say the grade was the most important thing in that process, and now that I’m an adult and I look back, I think I missed the boat that learning was the most important thing. We’re trying to make you lifelong learners, forever curious about the world around you, and if we could just take the emphasis off the grade and instead on the learning, I don’t think we’d see so much cheating. I think kids cheat because it’s grade-focused, and instead, if they would recognize it’s about the learning, it’s your integrity, your character, the kind of person you’re trying to become, then it’s a different focus.”

![Keep the New Gloves: Fighter Safety Is Non-Negotiable [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/ufcglovescolumncover-1200x471.png)

![Review: "Moana 2": Is the storyline just as intense as advertised? [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/1-copy-1024x538-1.webp)

![Review: Celebrating its 15th season, “Bob’s Burgers” renders itself a fan favorite [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/bobs-burgers-tv.jpg)

![Review: “Family By Choice” is the perfect watch that encapsulates family, love and everything in between [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/family-by-choice-1.png)

![Review: “A Phở Love Story” is an exceptional and authentic representation of teenage Vietnamese-Americans [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/a-pho-love-story-9781534441941_hr-786x1200.jpg)

![Review: “And the War Came” by Shakey Graves is the perfect year-round album [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_2665.jpeg)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)