College Board announces changes in instruction of AP Biology while postponing change in AP U.S. History

By Melinda Song

<[email protected]>

College Board’s Advanced Placement program is gaining popularity both at this school and around the world. According to an October 2010 press release, last school year marked a nine percent increase in AP course enrollment here. Moreover, according to the College Board, in 2009, 1.8 million students took more than 3.2 million AP exams.

However, with this upward trend, complaints have also been on the rise.

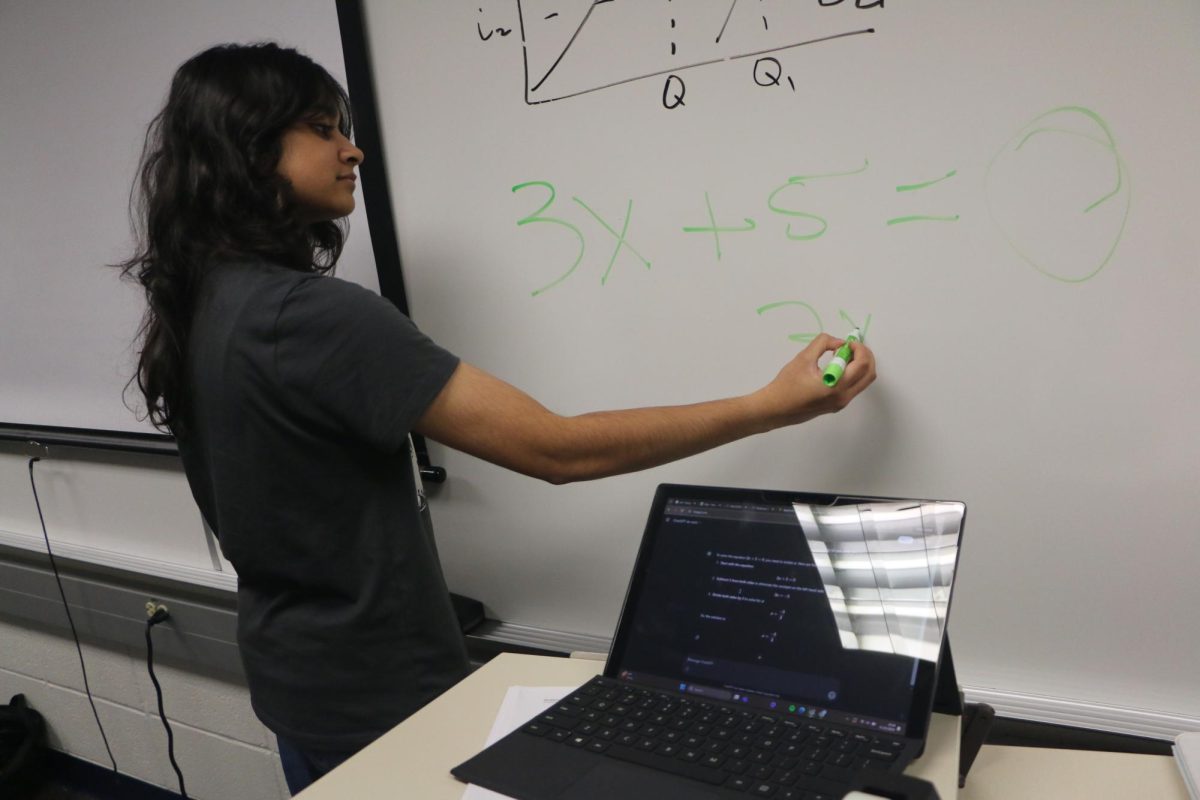

According to the New York Times article “Rethinking Advanced Placement”, the loudest of these voices targets the overwhelming amount of content required and lack of in-depth understanding within certain course curricula. The College Board has responded with the “New AP” program, which includes curriculum changes that will shift the instructional focus from breadth of material to depth of coverage in several of the 33 AP courses it offers.

The first AP course up for change is AP biology, which had about 173,000 exam takers in 2009. College Board publically released its changes to this course on Jan. 29.

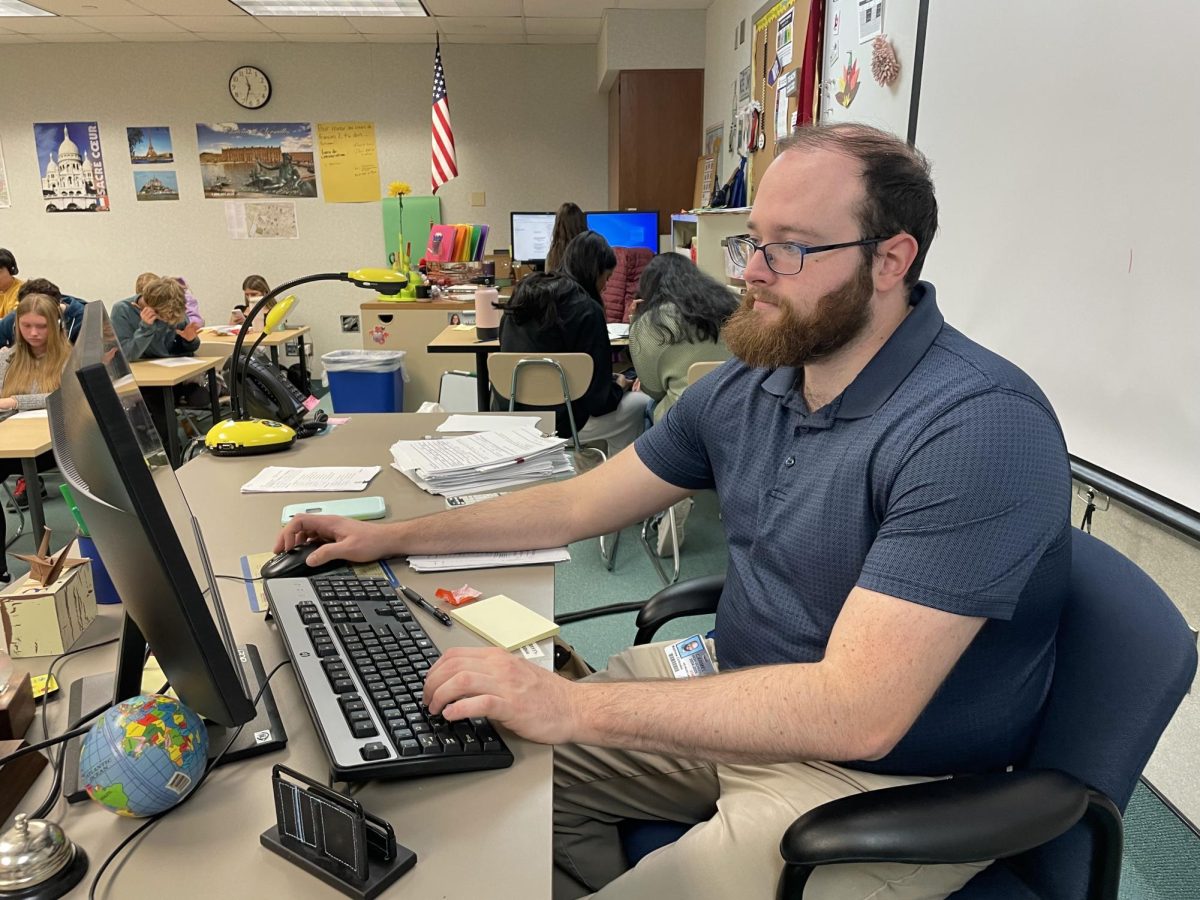

Tom Maxam, who has taught this course for 16 years, said there is evident room for improvement within it.

“The kids don’t learn enough process,” he said. “There’s too much memorization in AP bio, too much volume. If you saw how much anatomy and physiology I’m supposed to teach in five weeks, you wouldn’t believe it. It’s kind of like going to law school. While not academically super hard, the volume of material you have to learn is the difficult part.”

Despite the amount of material within in AP biology, however, senior Jeremy Weprich, who is currently taking this course, said knowing the fine details of biological processes is crucial to understanding overarching biological concepts.

“You can’t just understand why evolution happens because of the definition of evolution. Because it’s the AP and it’s a college-level course, you have to understand the actual elements, the biological elements, that make that up,” he said. “So instead of just knowing the definition, you really have to know the parts that equate to that larger picture.”

The AP program is designed to challenge students intellectually and better prepare them for college courses. In 2002, the National Research Council, a branch of the National Academy of Sciences, criticized AP science courses in general for failing to develop problem-solving skills through labs and experiments in their students. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, for example, stopped accepting college credit for AP biology in 2007 for this reason. According to Maxam, however, effective college preparation has not been a large issue in his class.

“The kids do fantastic with the course,” Maxam said. “I get e-mails from former students who said that they were beyond prepared, like they could teach the class when they go to college, even at Ivy League schools.”

Yet Maxam said he believes decreasing the amount of content and increasing the amount of critical thinking on the AP biology exam would ultimately be more beneficial.

“I think students will like the change. It’s a less frenetic pace,” he said. “I mean, we’re basically pouring the stuff down their throats. They learn it, but it’s pretty intense.”

Weprich said he agrees. Although changing the course to incorporate more analysis and problem-solving may make it more difficult, he said that the changes will help future science majors in the long run.

“If you’re applying the AP curriculum and the AP classes in the way that they are designed, like to look at college courses and prepare you for college, the projected changes are a much better route because in college, and if you’re studying biology, being a doctor or being a biologist is not about knowing multiple-choice answers. It’s not about being able to pick out one right out of four wrongs. It’s about applying it and using it, and that’s just the reality of the situation.”

AP U.S. history, a course that College Board also plans to revamp, is currently the most popular AP subject, with over 387,000 test takers in 2009. While initially the board planned to release changes to this subject along with AP biology, they have been postponed due to complaints of vagueness.

Social studies teacher Will Ellery, who has eight years of experience teaching this course, said he has a concern with College Board’s plan to reduce the amount of material students need to know for the national exam.

“There is a cause-effect relationship in all of history. And if we start eliminating prior history to just zero in on certain other parts of history, we may not understand the ramifications of what we’re looking at,” he said. “For example, if we look at political figures—if I were to look at America’s handling of imperialism at the end of the 19th century and early 20th century, we’re going to look at Theodore Roosevelt and his command of what happened with the Monroe Doctrine. Well, if you don’t understand the Monroe Doctrine, you’re not going to understand that. And if you’re not going to understand the Monroe Doctrine as a result of George Washington’s neutrality proclamation of 1793, then you really might not get the whole concept itself.”

After looking at the new curriculum College Board has created, AP teachers across the nation have echoed Ellery’s reservations. As a result, Packer said the board is still working and plans to make changes to U.S. history applicable to the 2014-15 school year.

“While there’s a lot of content (in AP U.S. history), the questions are actually analytical in nature—not just the free responses, not just document-based questions, but even the objective multiple choice questions are analytical questions. College Board wants to know what’s the significance and the cause-and-effect of certain events in history,” he said. “And that’s the difficulty if kids run into it without having taken an AP course before and without, really, having their eyes opened. They haven’t had the experience of taking analytical, objective exams so it’s not necessarily the amount of content to memorize as much as it is the ability to take that content and then analyze the application of that content.”

Weprich, who took AP block as a junior, shares this viewpoint.

“In history, the concepts that have to do with the dates and the facts and the people can be very easy to understand, but when you’re trying to think about overall changes and sociological trends and the themes that underlie historical movements—when you’re going into that deeper level of thinking, that’s a way to actually learn (history). And I think that’d be a really good way to improve the program: if the College Board really makes the kids go on that other level instead of just fact regurgitation.”

According to Ellery, one rumor about the changed curriculum is that it will decrease emphasis on about three hundred years of exploration and colonization. In addition, he said College Board will reduce the amount of pure memorization and increase the amount of critical thinking in what he likened to “trivial pursuit history.”

“(In) the 19th century for example, the only court cases I’m going to need to worry about are essentially going to be a couple of the ones from John Marshall up through Plessy v. Ferguson,” he said. “I’m not going to have to go through every court case, and the kids aren’t going to have to command all the court cases. I think what’s more important, what AP is going to be looking for, is an understanding of how America unfolded rather than this court case did this, and this court case did that.”

![Keep the New Gloves: Fighter Safety Is Non-Negotiable [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/ufcglovescolumncover-1200x471.png)

![Review: “We Live in Time” leaves you wanting more [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_6358.jpg)

![Review: The premise of "Culinary Class Wars" is refreshingly unique and deserving of more attention [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/MUSE-class-wars-cover-2.png)

![Introducing: "The Muses Who Stole Christmas," a collection of reviews for you to follow through winter [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/winter-muse-4.gif)

![Review: "Meet Me Next Christmas" is a cheesy and predictable watch, but it was worth every minute [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/AAAAQVfRG2gwEuLhXTGm3856HuX2MTNs31Ok7fGgIVCoZbyeugVs1F4DZs-DgP0XadTDrnXHlbQo4DerjRXand9H1JKPM06cENmLl2RsINud2DMqIHzpXFS2n4zOkL3dr5m5i0nIVb3Cu3ataT_W2zGeDAJNd_E-1200x884.jpg)

![Review: "Gilmore Girls", the perfect fall show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/gilmore-girls.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)