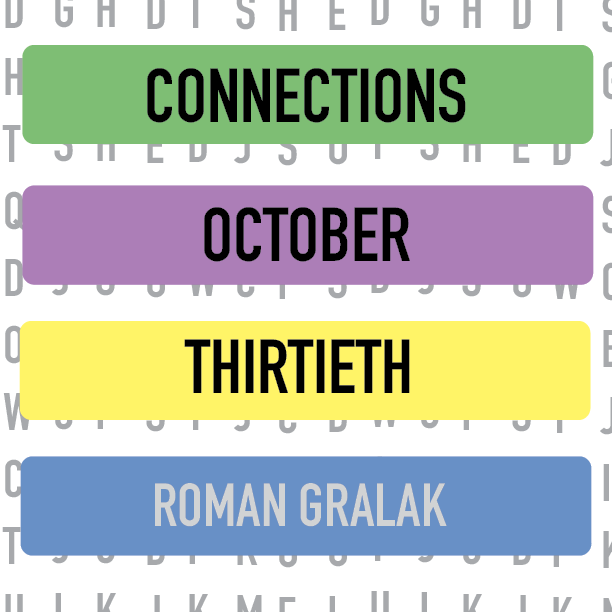

Look around and you’ll find that  there are opportunities everywhere to donate to good causes. October was National Breast Cancer Awareness Month, and, lo and behold, this month is National Lung Cancer Awareness Month (December is National Safe Toys and Gifts Month). With the variety of charities available within school and without, it doesn’t come as a surprise that the accumulation of charity projects makes global aid worth about $120 billion a year, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. While this is a large number worth noting, rarely do people delve beyond the surface of facts and figures to really think about how much that $120 billion has truly accomplished. A little research can go a long way when it comes to the impact of donations, and while the idea of unhelpful charities seems counterintuitive, we should be aware that there do indeed exist charitable organizations which do less good than we think, whether it is intentional or not.

there are opportunities everywhere to donate to good causes. October was National Breast Cancer Awareness Month, and, lo and behold, this month is National Lung Cancer Awareness Month (December is National Safe Toys and Gifts Month). With the variety of charities available within school and without, it doesn’t come as a surprise that the accumulation of charity projects makes global aid worth about $120 billion a year, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. While this is a large number worth noting, rarely do people delve beyond the surface of facts and figures to really think about how much that $120 billion has truly accomplished. A little research can go a long way when it comes to the impact of donations, and while the idea of unhelpful charities seems counterintuitive, we should be aware that there do indeed exist charitable organizations which do less good than we think, whether it is intentional or not.

In theory, the goal of every start-up aid agency should be to finish its job and close shop, like Livestrong did. While smaller charities adhere to this rule of thumb, larger organizations are not always as vigilant as Livestrong and instead put the focus on expansion. For these latter agencies, every new catastrophe in the world presents another opportunity to reap the profits. What was originally established as small-scale, temporary assistance becomes a sprawling network of aid which at worst replace governments, forcing them to be forever dependent on handouts. The problem becomes very real when aid agencies such as the United Nations are more concerned with justifying their own existence through charts and data than with producing actual results.

Another problem with some charities relates to the method through which facts and figures are gathered. According to UNICEF, 2.4 million Afghani girls are receiving an education at a school facility. This number alone seems to speak volumes of an aid program’s typical success story, but when we take a closer look at how they arrived at this number, we come across troubling realizations. In dangerous areas like Afghanistan, rather than personally executing the use of donation funds to promote education, UNICEF allows local third parties to allocate the funds as they see fit. The problem with this situation is immediately obvious: It is almost impossible to track the progress and use of funds by these third parties. As a result, the quantitative reports are highly unreliable and most likely defective.

Nevertheless, all aid programs start with good intentions. In 2007, the aid world unveiled an ambitious goal: eradicating malaria.

Case in point—Apac. People living in this African town face a constant battle with malaria, a disease which results annually in a total economic loss to Africa in the tens of billions of dollars. Global aid organizations with good intentions exist but are often led astray. Two of the foreign aid programs in Apac—a European-funded child-protection group and National Wetlands Program (NWP)—do not even address the malaria issue. In fact, the NWP prevents the draining of surrounding swamps that serve as breeding grounds for mosquitoes. Insecticide spray effectively cut malaria infections in half, but in 2008 the spray was discontinued by proponents of organic farming.

By being more cognizant of the credibility of the charity organizations, we can avoid falling into the trap of throwing money at a problem in false hopes of solving it. Organizations like the Better Business Bureau are only a click away and can help confirm the legitimacy of aid programs. Equipped with knowledge, we can make bigger differences in our community and the world.

![Keep the New Gloves: Fighter Safety Is Non-Negotiable [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/ufcglovescolumncover-1200x471.png)

![Review: “We Live in Time” leaves you wanting more [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_6358.jpg)

![Review: The premise of "Culinary Class Wars" is refreshingly unique and deserving of more attention [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/MUSE-class-wars-cover-2.png)

![Introducing: "The Muses Who Stole Christmas," a collection of reviews for you to follow through winter [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/winter-muse-4.gif)

![Review: "Meet Me Next Christmas" is a cheesy and predictable watch, but it was worth every minute [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/AAAAQVfRG2gwEuLhXTGm3856HuX2MTNs31Ok7fGgIVCoZbyeugVs1F4DZs-DgP0XadTDrnXHlbQo4DerjRXand9H1JKPM06cENmLl2RsINud2DMqIHzpXFS2n4zOkL3dr5m5i0nIVb3Cu3ataT_W2zGeDAJNd_E-1200x884.jpg)

![Review: "Gilmore Girls", the perfect fall show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/gilmore-girls.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)