The words “detention” or “see me after class” still held weight when I was in eighth grade at Creekside Middle School. The face of the person being called out might flush red, or perhaps he or she would get uneasy and break into a cold sweat as though he or she were going to be questioned about a murder.

The words “detention” or “see me after class” still held weight when I was in eighth grade at Creekside Middle School. The face of the person being called out might flush red, or perhaps he or she would get uneasy and break into a cold sweat as though he or she were going to be questioned about a murder.

Hence, when my eighth-grade wellness teacher called me over to “have a word,” I was less than thrilled about my suddenly and imminently doomed future.

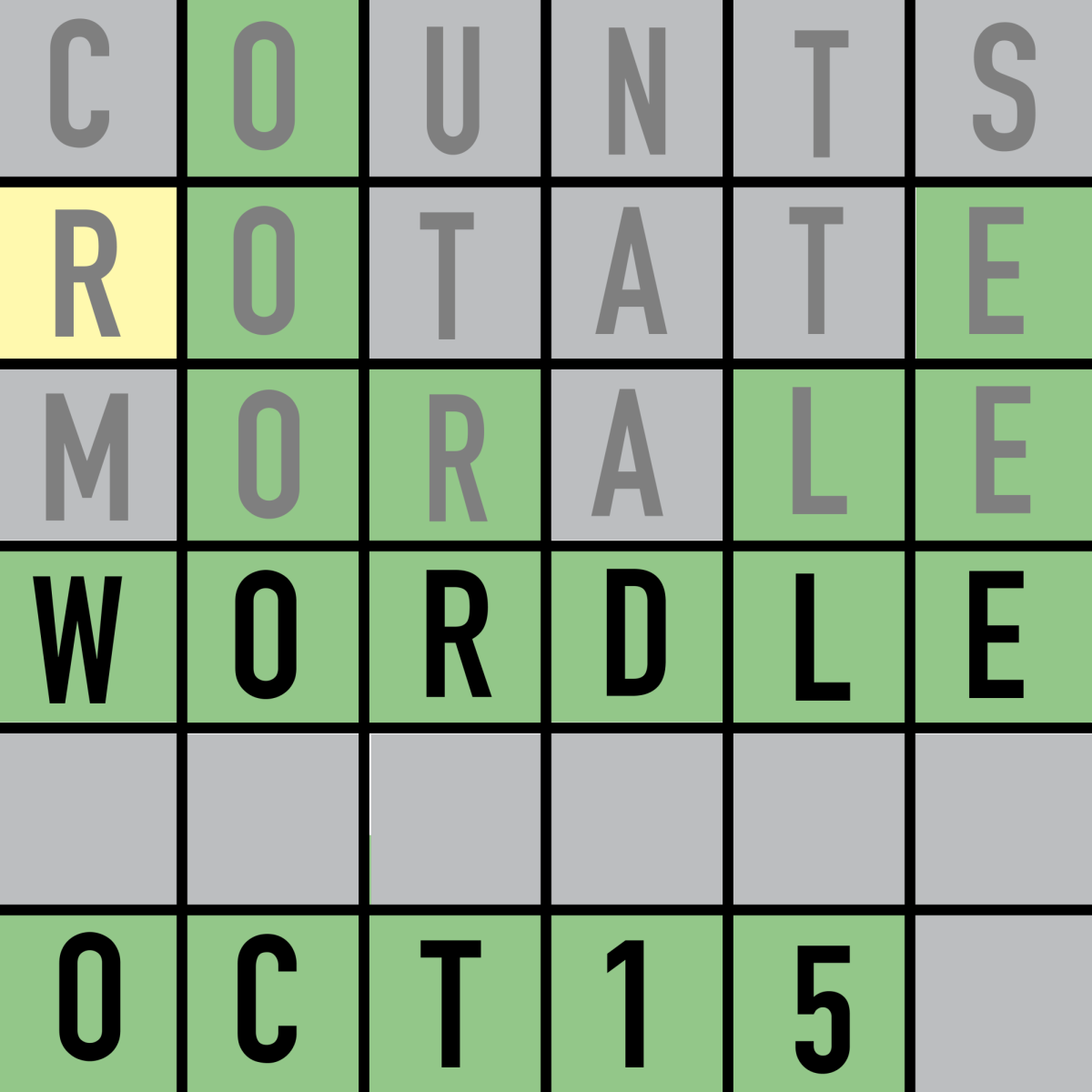

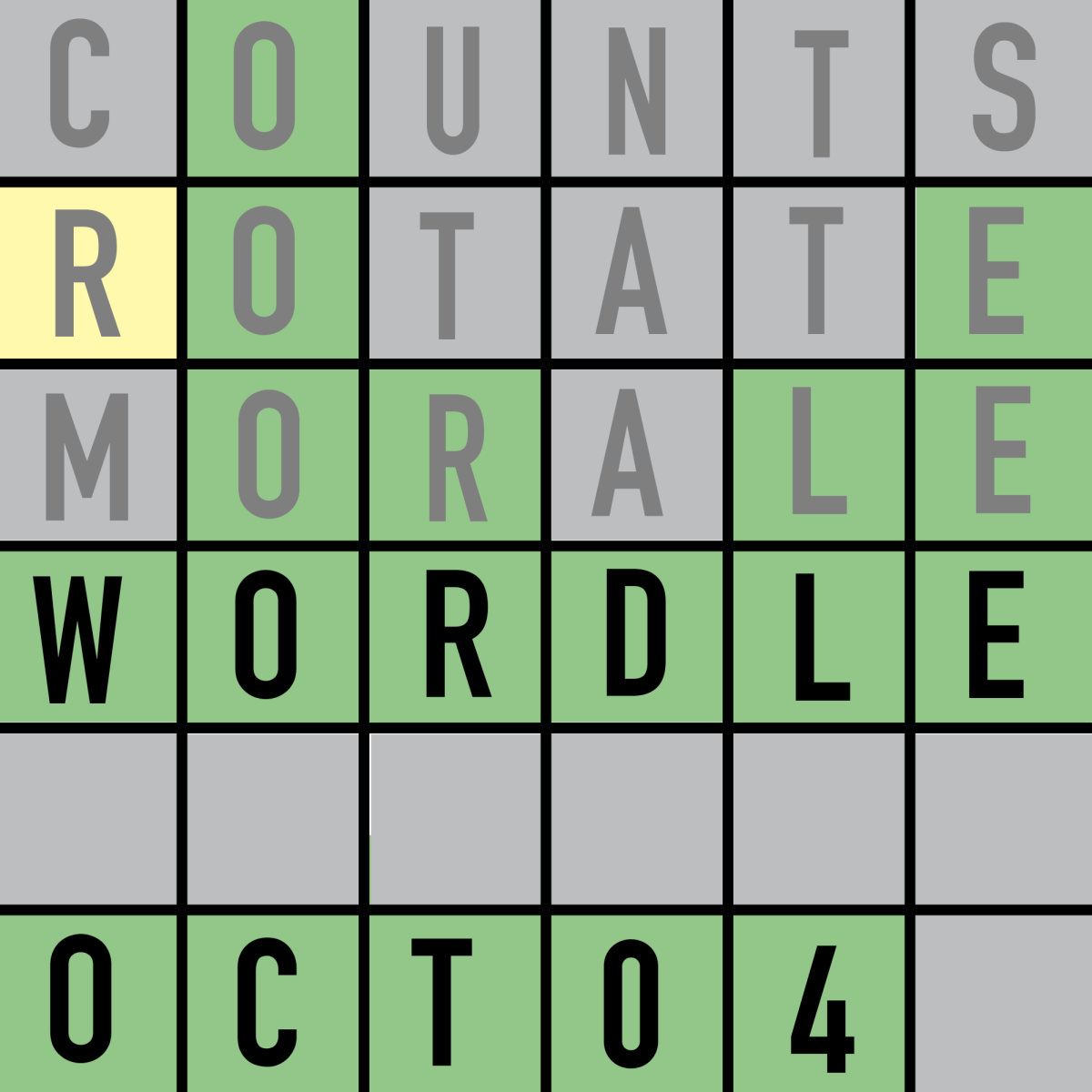

Evidently, she wanted to discuss a reflection I had completed in regards to a board game that was a new part of the D.A.R.E. (Drug Awareness Resistance Education) curriculum. In her words, I had been “really bitter” in my responses about the game’s effectiveness and what I had learned from it.

To her credit, the questioning was brief and minimally awkward, and she was tolerant and understanding of my perspective on the game. In my opinion, this is the manner in which drug education should be handled with students.

This is in sharp contrast to the ideology behind the board game “It’s Party Time” and D.A.R.E, the broader anti-drug program that is in place in 75 percent of our nation’s school districts, according to the D.A.R.E. America website.

“It’s Party Time” is a “realistic” Monopoly-style game in which groups are assigned a specific drug to be addicted to while trying to balance their finances and their health. Each square represents a situation, in which bad luck and irresponsibility mesh, which results in losing your cell phone or not paying your taxes. Strangely, most of these scenarios cost the same amount: $200. Included in an accompanying PowerPoint are even stranger events involving six-foot bongs and arson.

The problem with “It’s Party Time” is that it symbolizes a larger trend in drug education: using unrealistic situations and inaccurate or manipulated information. Many would argue that it doesn’t matter how we prevent adolescent drug abuse, as long as it works. However, that is precisely the issue with D.A.R.E.—simply put, it doesn’t work.

Since 1998, the Department of Education has forbidden schools from spending any of their funding on D.A.R.E. because of the program’s ineffectiveness and lack of scientific basis. Over 30 studies have reported that D.A.R.E. does not prevent drug use, and in some cases can have a boomerang effect, increasing drug use among its graduates.

Groups and individuals such as the American Psychological Association, the National Institute of Justice, the California Department of Education and former Surgeon General David Satcher have spoken out about the ineffectiveness of D.A.R.E. as a program. Gilbert Botvin, a doctor from Cornell Medical Center said, “It’s well-established that D.A.R.E. doesn’t work.” Former Salt Lake City mayor Rocky Anderson called it “a fraud on the people of America.” In fact, the original 1992 study that showed hallucinogenic drug use to significantly increase among D.A.R.E. graduates versus non-graduates came from IU. The list goes on.

In contrast to D.A.R.E, harm-reduction groups like DanceSafe help the community by disseminating information about drug effects and safety. For example, DanceSafe offers MDMA pill testing kits to test for adulterants in tablets of unknown purity. They also circulate potentially life-saving information about MDMA and other drugs in a more accessible, friendly and scientifically-based environment than D.A.R.E.

With the recent popular votes to legalize marijuana in Colorado and Washington, as well as the addition of a permanent drug dog here, drug education in schools is rapidly becoming more relevant than ever. If we fail to learn from our mistakes, as the D.A.R.E. program and “It’s Party Time” have proven to be, we are certainly doomed to repeat them.

![Keep the New Gloves: Fighter Safety Is Non-Negotiable [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/ufcglovescolumncover-1200x471.png)

![Review: “We Live in Time” leaves you wanting more [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_6358.jpg)

![Review: The premise of "Culinary Class Wars" is refreshingly unique and deserving of more attention [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/MUSE-class-wars-cover-2.png)

![Introducing: "The Muses Who Stole Christmas," a collection of reviews for you to follow through winter [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/winter-muse-4.gif)

![Review: "Meet Me Next Christmas" is a cheesy and predictable watch, but it was worth every minute [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/AAAAQVfRG2gwEuLhXTGm3856HuX2MTNs31Ok7fGgIVCoZbyeugVs1F4DZs-DgP0XadTDrnXHlbQo4DerjRXand9H1JKPM06cENmLl2RsINud2DMqIHzpXFS2n4zOkL3dr5m5i0nIVb3Cu3ataT_W2zGeDAJNd_E-1200x884.jpg)

![Review: "Gilmore Girls", the perfect fall show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/gilmore-girls.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)