On June 15, 2013, 16-year-old Ethan Couch drove his father’s Ford pickup truck to a Walmart near Fort Worth, TX, where surveillance cameras captured him stealing two cases of beer. With seven passengers in the vehicle, Couch had a blood alcohol content triple the legal limit for adults and was driving almost twice the speed limit when he struck a broken-down SUV and a few pedestrians near it, killing four of the people and injuring nine. Couch, whose family is affluent and well-known in owning the business Cleburne Metal Works, is reported to have said at the scene to one of his passengers, “I’m Ethan Couch; I’ll get you out of this.”

On June 15, 2013, 16-year-old Ethan Couch drove his father’s Ford pickup truck to a Walmart near Fort Worth, TX, where surveillance cameras captured him stealing two cases of beer. With seven passengers in the vehicle, Couch had a blood alcohol content triple the legal limit for adults and was driving almost twice the speed limit when he struck a broken-down SUV and a few pedestrians near it, killing four of the people and injuring nine. Couch, whose family is affluent and well-known in owning the business Cleburne Metal Works, is reported to have said at the scene to one of his passengers, “I’m Ethan Couch; I’ll get you out of this.”

On Oct. 6, 2011, a then-14-year-old African American boy jumped out of a Cadillac he had been riding with two friends and punched Mark Gregory, who stood 5 feet, 1 inch tall and weighed 106 pounds, according to the Tarrant County District Attorney’s Office. Gregory fell, hitting his head on his way down, and died two days later from the injury sustained in the incident. Although the teenager admitted to the act, prosecutors say he did not express remorse for the murder of Gregory.

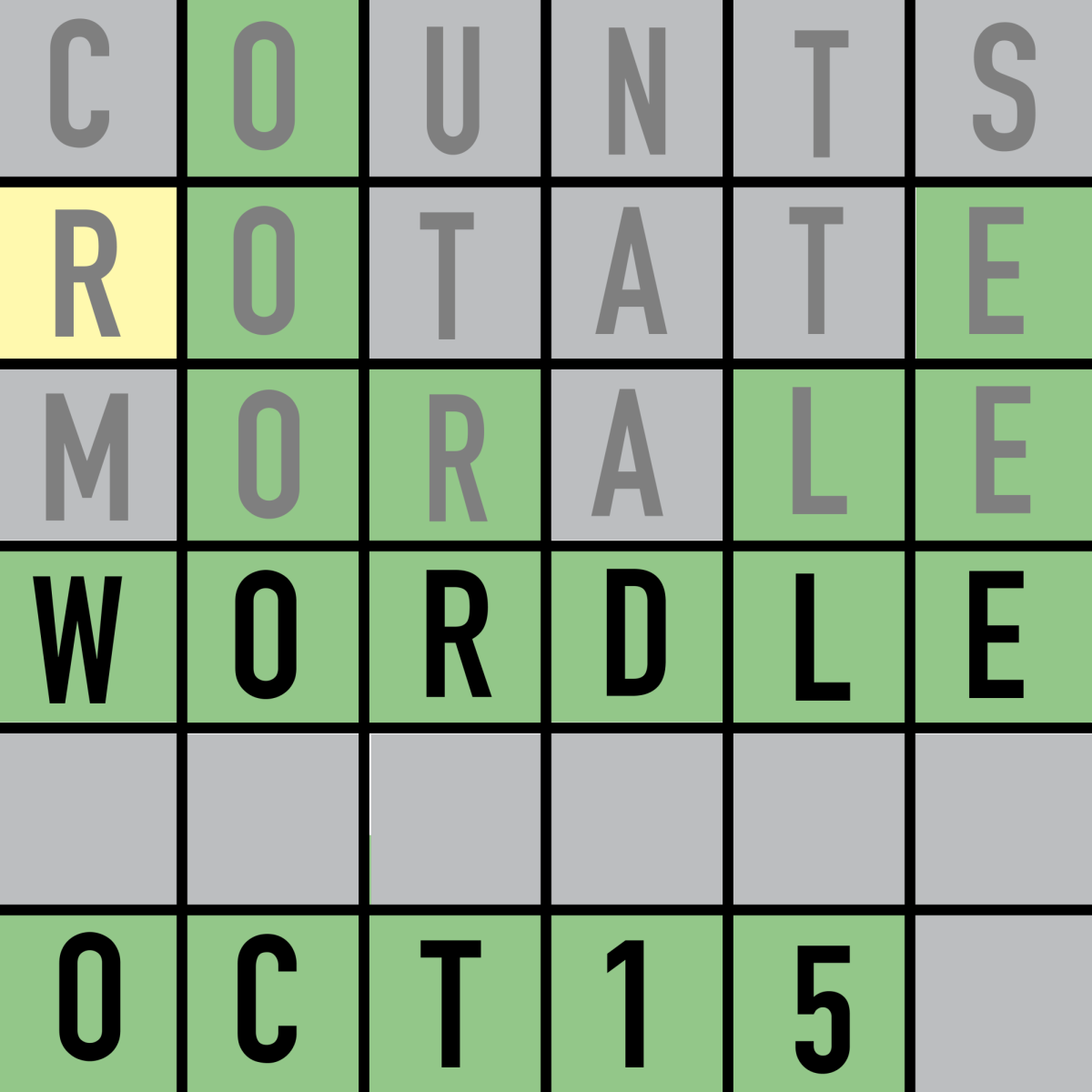

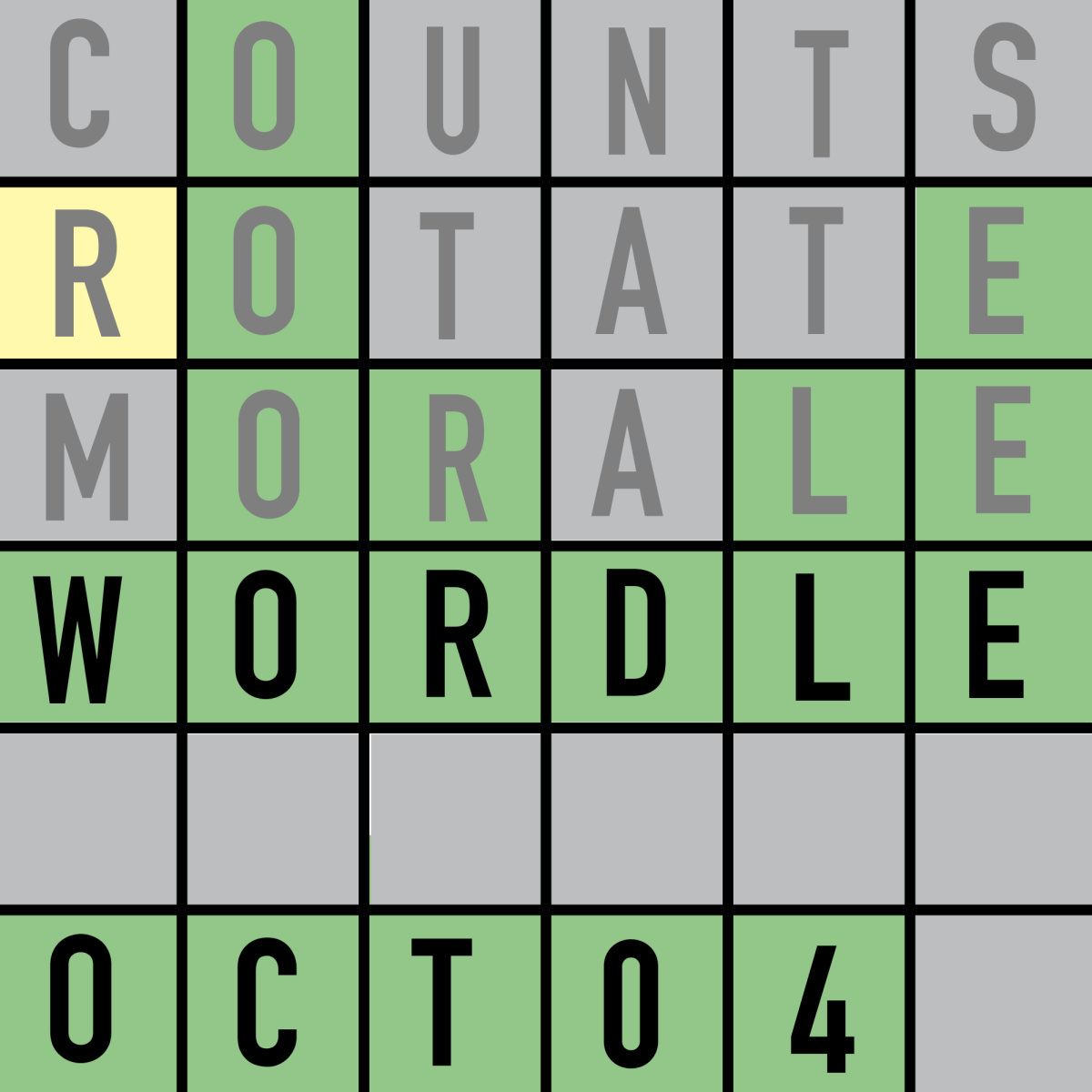

There exists a period of almost two years separating the times of these crimes, and their perpetrators are a world apart in terms of their upbringings and lifestyles. The primary link between these two boys is that they were both handed sentences by Judge Jean Boyd of Fort Worth, TX, making a wide disparity in their punishments a cause of outrage among many Americans. While the unnamed boy is currently serving a 10-year sentence in the state prison, the sentence of Ethan Couch, delivered Dec. 12, 2013, consists of 10 years’ probation, some of which he will spend in expensive therapy in California.

The unnamed teenager and Couch committed similarly reprehensible crimes and received different sentences from the same judge. Why is it, then, that the former faces 10 years of incarceration, while the latter can look forward to equine therapy and yoga at a rehabilitation home in ritzy Newport Beach, CA?

“In its majestic equality, the law forbids rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges, beg in the streets and steal loaves of bread,” wrote French poet and journalist Anatole France. But statistics suggest otherwise.

According to a factsheet by Political Research Associates, more than half of all state prison inmates in 1991 reported an annual income of less than $10,000 prior to their arrest. Eighty percent of working male Americans are employed full-time, compared to 55 percent of state prisoners reportedly working full-time at the time of arrest. Somewhat ironically, in 2001, the United States spent $167 billion dollars on policing, corrections, judicial and legal services and $29.7 billion on Temporary Aid to Needy Families (TANF).

It is easy to point to the prevalence of white-collar crime rather than blue-collar crime among the wealthy class as a reason. The tendency to dismiss white-collar crime as “victimless” is disturbing enough, but more disturbing is the fact that seeming special treatment for the rich extends beyond that to violent crime. We see this in O.J. Simpson’s infamous murder trial, from which he walked free to inspire national outrage. We see this in atrocities committed by the U.S. government at Guantanamo Bay and Abu Ghraib, where acts have gone unpunished because of their proximity to the government and thus to the wealthy and powerful. We see this in the punishment of Ethan Couch, who took four lives and destroyed several more, whose destructive and self-centered tendencies—allegedly due to his family’s wealth—are to be treated through still more privilege and luxury.

“What is the likelihood if this was an African-American, inner-city kid that grew up in a violent neighborhood to a single mother who is addicted to crack and he was caught two or three times…what is the likelihood that the judge would excuse his behavior and let him off because of how he was raised?” asked psychologist Suniya S. Luther of the verdict in Couch’s case. In an ideal world, her question would not be raised, but to be fair, criminal justice would not be a necessity in such a society. We do not live in an ideal world, so perhaps it’s time to stop accepting a broken justice system and strive for a better reality.

The views in this column do not necessarily reflect the views of the HiLite staff. Reach Kyle Walker at [email protected].

![Keep the New Gloves: Fighter Safety Is Non-Negotiable [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/ufcglovescolumncover-1200x471.png)

![Review: “We Live in Time” leaves you wanting more [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_6358.jpg)

![Review: The premise of "Culinary Class Wars" is refreshingly unique and deserving of more attention [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/MUSE-class-wars-cover-2.png)

![Introducing: "The Muses Who Stole Christmas," a collection of reviews for you to follow through winter [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/winter-muse-4.gif)

![Review: "Meet Me Next Christmas" is a cheesy and predictable watch, but it was worth every minute [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/AAAAQVfRG2gwEuLhXTGm3856HuX2MTNs31Ok7fGgIVCoZbyeugVs1F4DZs-DgP0XadTDrnXHlbQo4DerjRXand9H1JKPM06cENmLl2RsINud2DMqIHzpXFS2n4zOkL3dr5m5i0nIVb3Cu3ataT_W2zGeDAJNd_E-1200x884.jpg)

![Review: "Gilmore Girls", the perfect fall show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/gilmore-girls.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)