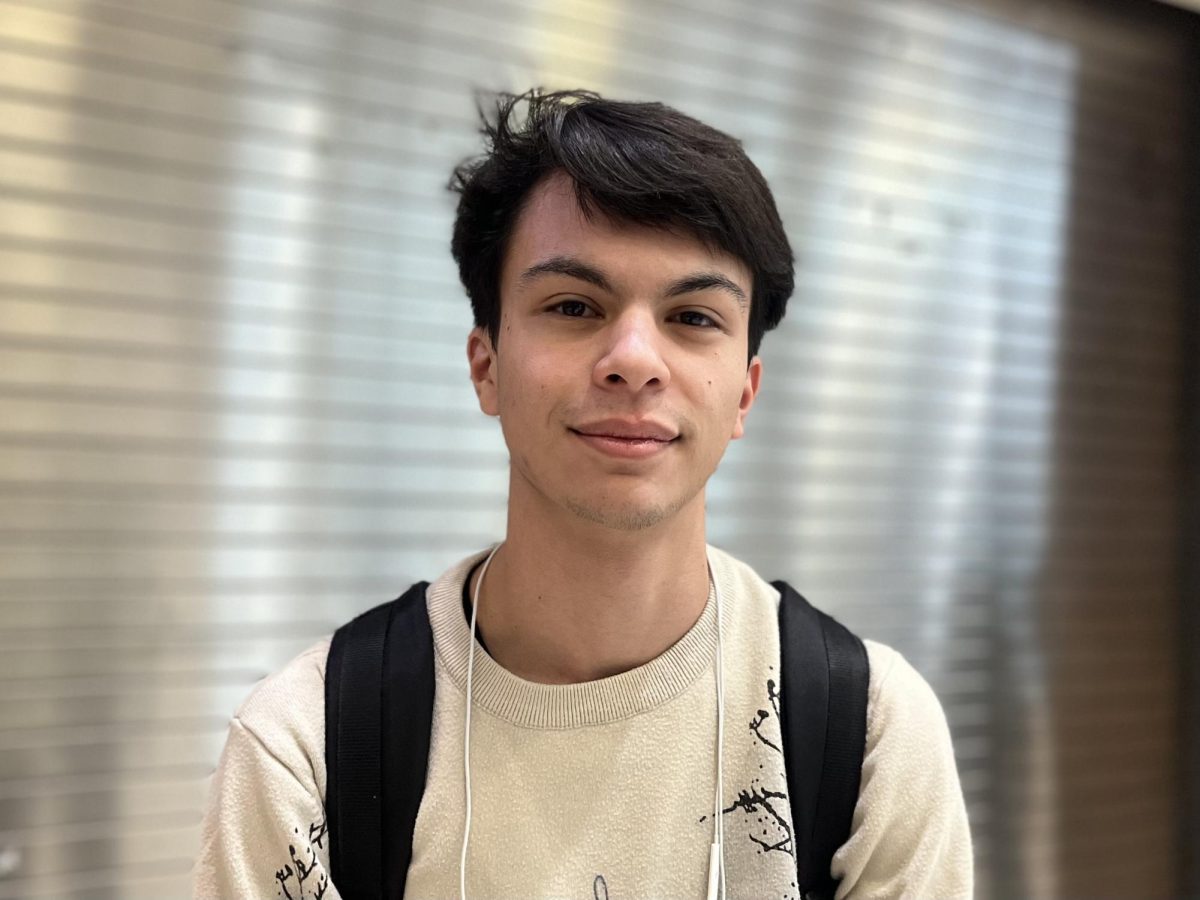

Completing a 2.4-mile swim, 112-mile bike ride and a 26.2-mile run in one day are usually beyond the average person’s physical reach.

Such is not the case for senior Eric Zigon, who entered the world of extreme athletics when he successfully completed the Ironman Louisville triathlon this August.

“I was just thinking about things that I want to accomplish in my lifetime, and I was like, I kind of want to do an Ironman one day,” Zigon said. “Then I decided, why wait? And I signed up two weeks later and started training.”

According to Nancy Henein, who holds a master’s degree in sport and exercise psychology and treats competitive athletes as part of her practice, extreme sports participation has more than tripled over the past three years. Despite this rise, she said little research has been conducted to understand the full picture behind this “movement.” Zigon’s experience thus sheds light on what motivates these athletes to participate and reveals potential benefits those athletes attain.

Training Process

A grueling training effort precedes any extreme athletes’ success. According to Lindsey Langford, a former athletic trainer for competitors in high endurance sports, motivation can either be internal or external. For Zigon, his motivation—Zigon paid his own $625 registration fee—was

exclusively intrinsic.

“I had 625 bucks riding on the fact that I would finish,” he said. “So whenever I was training, I was like, ‘OK, you paid for this. You’re in it. You need to finish. You don’t want to get there and not finish and feel terrible about yourself for the next year when you start training for it again.’”

Once the training process begins, differences between physical preparation for regular sports and extreme athletics manifest. Langford said that, in general, extreme sports require a greater time commitment than any other sports do. Zigon, who trained approximately seven months for the Ironman triathlon, said his training regimen during the summer consisted of an hour-long swim, a three-hour-long bike ride and an hour-and-a-half run almost every day.

According to Tim Mylin, women’s track and field head coach and active long-distance runner, the same level of commitment is required for a prospective marathon runner.

“It’s more demanding and more time-intensive to train for a marathon,” he said. “You have to commit a pretty significant amount of your day to training if you’re doing those ultra-type events versus if you’re a track athlete and the farthest you’re ever going to run is two miles in a race.”

Mental Preparation

Yet physical preparation is only one part of an athlete’s training process, especially for those at a high level, according to Henein.

“For top athletes, most have what it takes physically,” she said via email. “It’s the mental component that tends to separate the best of the best.”

Zigon said strong mental preparation was responsible for 90 percent of his success as an

extreme athlete.

“At any point in time, you’re not going to be feeling good physically. So mentally you have to tell yourself that you can go further; you can do more. A lot of people will start feeling pain, and they’re like, ‘I’m done; I quit,’” he said. “But really, it’s the mental aspect that will push you to do better and finish things that you never thought you could.”

To combat anxiety, Langford said she recommends extreme athletes subdivide the given task into manageable parts in order to take “incremental baby steps.” That way an athlete isn’t overwhelmed by such a mentally and physically tolling task all at once, and can better achieve his or her goal. Zigon said he used this strategy while competing.

“When you’re at the race, you think about all the training that you’ve done and what you’ve accomplished. A big part of it is just forgetting about what you’ve already done during the day,” he said. “You have to break it up into smaller segments; otherwise it’ll get kind of intimidating and overwhelming.”

Mylin, who has completed four marathons and 30 to 40 half-marathons, said he tries to maintain an optimistic outlook prior to competing in a long-distance race in order to combat anxiety and fear. This state of mind helps Mylin overcome his mental obstacles.

“I’ve got a saying that I’ve used for years,” he said. “Fear sees the obstacle; faith sees the opportunity… Fear tends to paralyze your performance whereas if you have an optimistic outlook, you have a much better chance of performing well.”

Benefits of Participating

Due to the involved nature of xtreme sports, extreme athletes receive unique health benefits. Zigon, who used to dive and now plays rugby and swims, said what he gained physically from the Ironman triathlon will help him in other athletic endeavors.

“I’ve never been a runner or a cyclist or, really, a swimmer,” he said. “(Training) gave me a lot of cardiovascular endurance that I never had.”

Also, benefits of training for endurance sports can carry into other aspects of life. According to Mylin, his athletic lifestyle and occasional marathon training have bettered

his self-discipline.

For Zigon, who said he plans to complete two or three more Ironman triathlons in the next season, training for the Ironman gave him a better work ethic, along with other positive qualities.

“You find out a lot about who you are as a person. When you put yourself through a lot of pain, you figure out your limits, and then you push past those,” he said. “You definitely gain a lot of self-confidence whenever you finish something that large, and you feel pretty good about yourself because not a lot of people finish that in their lifetime, especially as an 18 year old.”

![Keep the New Gloves: Fighter Safety Is Non-Negotiable [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/ufcglovescolumncover-1200x471.png)

![Review: “We Live in Time” leaves you wanting more [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_6358.jpg)

![Review: The premise of "Culinary Class Wars" is refreshingly unique and deserving of more attention [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/MUSE-class-wars-cover-2.png)

![Introducing: "The Muses Who Stole Christmas," a collection of reviews for you to follow through winter [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/winter-muse-4.gif)

![Review: "Meet Me Next Christmas" is a cheesy and predictable watch, but it was worth every minute [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/AAAAQVfRG2gwEuLhXTGm3856HuX2MTNs31Ok7fGgIVCoZbyeugVs1F4DZs-DgP0XadTDrnXHlbQo4DerjRXand9H1JKPM06cENmLl2RsINud2DMqIHzpXFS2n4zOkL3dr5m5i0nIVb3Cu3ataT_W2zGeDAJNd_E-1200x884.jpg)

![Review: "Gilmore Girls", the perfect fall show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/gilmore-girls.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)