For Ella Yates, leader of the green action Club’s (GAC) tree planting initiative and senior, parks are not just a place to enjoy nature; they are a place to maintain it.

“The parks are very important for a couple different reasons. Obviously, they are a habitat for animals, plants and trees which are really good for sucking carbon out of the air,” Yates said. “I know it doesn’t seem like just one tree is super effective, but throughout its lifetime it can take a couple cars’ emissions out of the sky, which is pretty cool.”

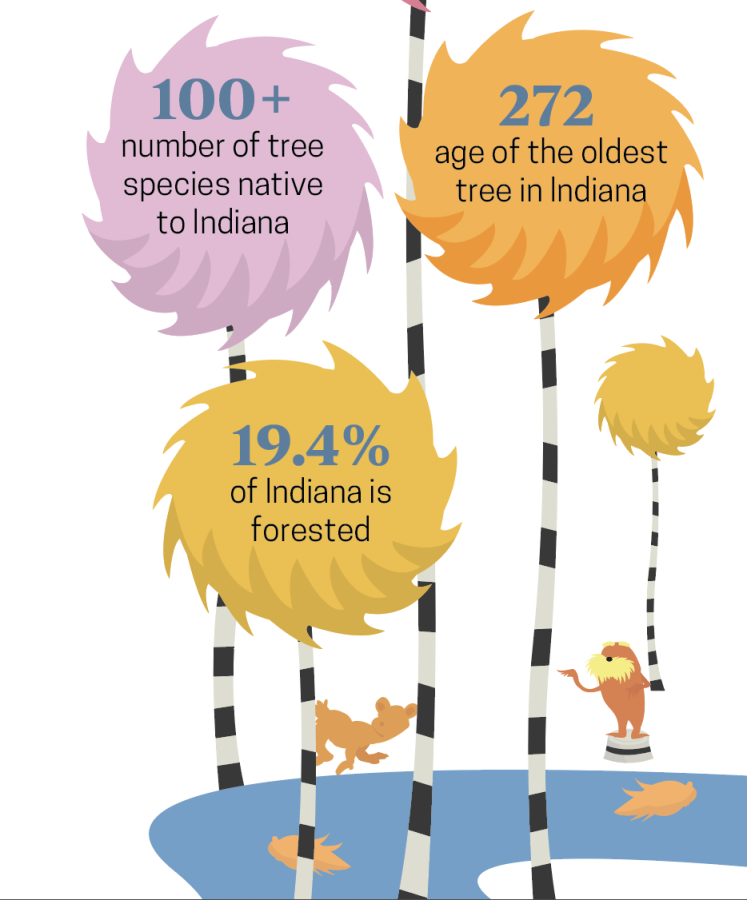

Yates is not alone in this sentiment. In fact, according to the National Recreation and Park Association, trees in urban areas eliminate over 90 million metric tons of carbon emissions per year. To put this in perspective, this is equivalent to getting rid of over 19 million cars.

It is important to note that the federal government utilizes the National Park Service (NPS), an agency of the Department of the Interior established in 1916, to manage hundreds of national parks including the famous Yellowstone National Park. But despite such efforts, around 54% of Americans still say the federal government is not doing enough to protect national parks, according to a 2020 Pew Research Center study.

Many environmentally-conscious people in this community said they believe the government could do more and that efforts should not be limited to just national parks but rather should apply to the conservation of local parks and state parks as well.

Further exemplifying this importance, Svitlana Ramer, volunteer coordinator for Carmel Clay Parks and Recreation (CCPR), said such maintenance is necessary due to the benefits these parks provide for the community. Ramer said these include storm water control.

Further exemplifying this importance, Svitlana Ramer, volunteer coordinator for Carmel Clay Parks and Recreation (CCPR), said such maintenance is necessary due to the benefits these parks provide for the community. Ramer said these include storm water control.

“Carmel is a pretty built-up community; there’s a lot of roads, there’s a lot of parking lots, there’s a lot of residential developments—when the rain comes, it has nowhere to go,” Ramer said. “It needs to run off somewhere and get into the ground. It can get through concrete or pavement and so parks provide really valuable areas for the water to go into the ground or into ‘bioswales’ so that the rest of the town doesn’t get flooded. So we need these areas of open earth with plants and trees that will take up all of that water.”

According to National Geographic, there are several human-induced phenomena that can damage parks such as climate change and littering, as well as water and air pollution. However, according to Biology teacher Fran Rushing, one issue that people may often overlook are invasive species.

“(When) there’s no control over (the) growth of the invasive species, there’s nothing that’s preying on it or controlling and minimizing its growth. So it just has a population explosion,” Rushing said. “And when it does that, it can crowd out and take the place of the natural species that were there and had evolved to be there. And by changing that whole system, it could potentially cause some pretty serious damage.”

According to the NPS, community members can reduce the amount of invasive species through simple tasks such as planting native plants and cleaning shoes before walking in the parks.

However, with regards to the development of local parks, Ramer said, there is a fine line between making environmentally-friendly decisions while also adhering to community desires as seen in Bear Creek Park.

“That’s the dance, that’s the magic, that’s making sure that all of that can happen because we can’t…So we try to strike that fine balance the best we can while staying within the budget,” Ramer said. “And while also keeping in mind that we don’t do things that are unreasonable when it comes to natural resource management because that’s what the backbone of the park system is. We need to do good, do good by nature and do good by the people.”

Additionally, Ramer said the public can also play a role in maintaining this backbone of a healthy environment. This can be done through avoiding planting invasive species that can, in turn, harm the local parks by entering them and drive out native plant species.

“(The) Citizen Science programs allow non-scientists to collect scientific-grade data as volunteers,” Ramer said. “And so we currently have five tracks of citizen science. We have bird monitoring, bluebird monitoring— specifically because bluebirds are such an important indicator species—Hoosier Riverwatch stream monitoring, native plant monitoring and invasive plant monitoring.

“So these people have to volunteer three hours a month. And they go out and they have special applications. And they collect data about the types of plants and animals that we have in our parks. And so at the end of the month, our natural resources coordinator (Nicole Ledwith) pulls all of this data. She’s able to tell if our bird monitors found this many of these different types of birds in our habitats are doing pretty well, or if our bluebird monitors said that this many bluebirds laid eggs, and that many little blue birds hatched this summer.”

Furthermore, Yates said she regularly volunteers with the CCPR and encourages others to do the same in order to gain an enlightening and educational experience.

“Last Saturday, I actually picked up trash off the Monon (Trail) with this group. It didn’t seem like there was a lot but after walking around for like an hour or so I had like a full trash bag full of just litter so that was interesting. I’ve also helped with stream monitoring and so I’ve been able to learn why these things are important,” Yates said. “It’s different than just going to the park on the weekends—getting behind the scenes and helping out is really important.”

![Keep the New Gloves: Fighter Safety Is Non-Negotiable [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/ufcglovescolumncover-1200x471.png)

![Review: “We Live in Time” leaves you wanting more [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_6358.jpg)

![Review: The premise of "Culinary Class Wars" is refreshingly unique and deserving of more attention [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/MUSE-class-wars-cover-2.png)

![Introducing: "The Muses Who Stole Christmas," a collection of reviews for you to follow through winter [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/winter-muse-4.gif)

![Review: "Meet Me Next Christmas" is a cheesy and predictable watch, but it was worth every minute [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/AAAAQVfRG2gwEuLhXTGm3856HuX2MTNs31Ok7fGgIVCoZbyeugVs1F4DZs-DgP0XadTDrnXHlbQo4DerjRXand9H1JKPM06cENmLl2RsINud2DMqIHzpXFS2n4zOkL3dr5m5i0nIVb3Cu3ataT_W2zGeDAJNd_E-1200x884.jpg)

![Review: "Gilmore Girls", the perfect fall show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/gilmore-girls.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)