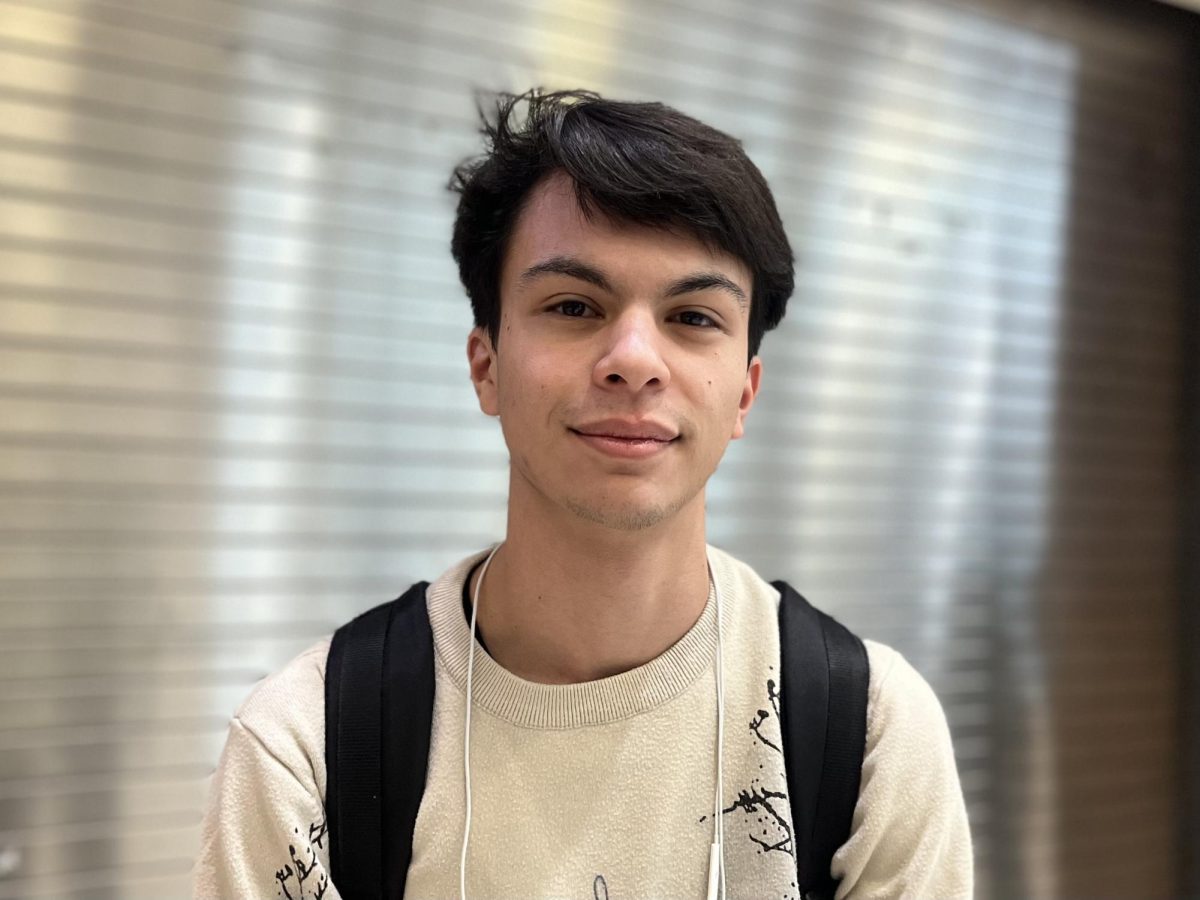

Ever since senior Tristan Schilling was 10 years old, he assumed he was broke. There were times when his parents could not pay the bills. There were nights they spent without electricity. There were days they spent without running water.

“Since we never really had any money, I always thought of myself as broke, and that’s how I had gone about living my life, not spending any money. I’ve never really asked my parents for anything because I knew if I asked them, then that was money we could not spend on bills, which meant we had to sacrifice something important,” Schilling said.

Schilling’s situation echoes across America. His financial situation is among the bottom half of the growing income gap between the upper class and the lower class. According to a 2014 study conducted by Pew Research, U.S. income inequality is currently the highest it has ever been since 1928. In fact, the study also reported that the United States is more unequal than most of its developed-country peers.

Indiana fits right into this mold. Currently, according to the National Center of Education Studies, 46.8 percent of Indiana public school students are eligible for free or reduced lunch. This is 17.6 percent higher than the 29.2 percent of students eligible in 2000. Specifically in Carmel, the median income is over double the median income for Indiana. It is at $107,505 compared to $43,374.

Searching for a Solution

From the time he turned 14, the legal minimum working age, Schilling was in search for a job. He said it was like an awakening. Throughout his childhood, he wanted to work and make his own money. Now, he finally could.

However, all this did not become a reality for Schilling until one day in late July last year. That morning, Schilling applied for a job at Noodles and Company. Within two hours, he was called in for an interview, and about four hours later, he was hired.

“That day was awesome because it felt like what I do actually matters because now I can, and I do, pay some of the bills at my house,” Schilling said. “I’ve paid for the electricity and the phone.”

Since last summer, Schilling has been working nearly every day. He usually starts working right after school and comes home anywhere from 9 to 11 p.m. Sometimes he picks up extra shifts during the week, and on the occasional Saturday, he works the 12-hour shift.

According to Schilling, he never considered coming from a low-income household to be a struggle. He said it is just a matter of working around the situation to find a viable solution.

“There have been times when my family didn’t have money to pay our water bill or something like that, and we had to sneak around back to one of the houses we used to live in before for running water,” Schilling said. “And the thing is, people (here) don’t know where you’re coming from.”

Schilling said that the hardest part was the lack of awareness. Schilling did not have a computer at his house until he was 10 years old. He did not have a word processing system until he was 16 years old.

“One thing that really irritated me when I was younger was that all my teachers just automatically assumed that all of the students had computers. The thing is, not everyone did. I didn’t, so basically I would try to finish stuff at school and then the stuff I didn’t finish, I just didn’t finish,” Schilling said.

He said the same currently holds true in his life. He considers work to be a necessity, so oftentimes other activities have to be pushed to the backseat.

“When you come from the kind of background I come from, the divide between want and need becomes crystal clear. You may want something, but you need food, you need water. That’s where the whole hesitation to ask for money comes in. You can’t ask for money to go out with friends when actually you should be helping with the bills,” Schilling said.

Not So Fortunate

According to social worker Jane Wildman, there is a significant portion of students at CHS who fall into the same financial category as Schilling. Wildman said that the stereotype of Carmel as an affluent community is so strong that the majority of people do not even realize that there are others who do not fit this label.

“When I go to meetings and my colleagues find out that I’m a social worker at Carmel High School, they say ‘What do you do? You guys don’t have any problems.’ Well, nothing infuriates me more because of course we have problems,” Wildman said. “I’m just here for the students. My job is to set a student up for success, and a lot of students just have so much going on in their lives at home that people aren’t aware of. I’m here to help them get through it.”

“When I go to meetings and my colleagues find out that I’m a social worker at Carmel High School, they say ‘What do you do? You guys don’t have any problems.’ Well, nothing infuriates me more because of course we have problems,” Wildman said. “I’m just here for the students. My job is to set a student up for success, and a lot of students just have so much going on in their lives at home that people aren’t aware of. I’m here to help them get through it.”

According to Wildman, 8 percent of the students at CHS are eligible for free or reduced lunch. Recently, the school started a new program in which the school uses food donations to fill backpacks and hands them out to students who need them. Later, the student returns the backpack, and the school refills it with donations.

“In the past, I’ve had cafeteria workers call me and tell me that so-and-so isn’t eating lunch,” Wildman said. “I then have them sit down and try to get them to tell me what the problem is. Oftentimes they tell me that they don’t have enough money right now, so they are not asking for lunch money, or they are saving the money to help get something at home.”

Wildman said she has a fund given to her by the school to help students purchase things like prom tickets, Homecoming tickets or athletic passes if they cannot afford them.

She said, “We don’t want students, through no fault of their own, to miss out on these kind of activities that shape a student’s high school experience.”

According to Wildman, coming from this kind of situation compels the student to grow up faster. She said that sometimes it allows them to be mature, but other times their financial situation just becomes a burden that is not meant to be carried by teenagers.

The Value of a Dollar

According to Schilling’s mother, Shannon Schilling, coming from a low-income family did not make her son a target for bullying while growing up; however, it did force him to earn many of the things she wishes she could have provided for him.

“He knows the value of the dollar, and how it really does not go a long way anymore. A lot of young people, when they graduate high school or college, do not really understand what can happen if you go into debt or lose a job,” Ms. Schilling said. “He already knows that. He saves his money and knows that he has to spend it responsibly.”

Ms. Schilling said her son has had to work hard to make his own money to buy things that most people just expect their parents to take care of, but she could not provide.

“One of Tristan’s achievements is definitely buying his car. He earned his own money to buy it, put himself through driver’s (education) and pays the insurance monthly. He recognized that he had to work for it by himself, and he did just that,” Ms. Schilling said.

Tristan said his life motto will always be to live below his means regardless of his financial situation. He said that while working, he sees little kids with iPhones. While driving in the school parking lot, he sees teenagers driving brand new luxury cars.

“Some of the people here, not to sound stereotypical, don’t know the true value of money,” Tristan said. “For many people, their parents have basically bought them whatever they need, and they don’t really know what it takes to make their own money.”

Originally, Tristan started working last summer to buy a car for himself. Over the summer, he worked full-time every day so that he could purchase the car independently. His expenses for the car included repairs, gas and insurance, all of which he was determined to pay on his own.

Tristan said it’s not as difficult as it may sound, “You just work, work and work, and pretty soon you will have the money.”

After forwarding every paycheck toward the car, Tristan did have enough. He bought the car with one of its seats stuck so far back that he had to outstretch his arm to reach the steering wheel and a door that just would not open.

“I pay for my own gas. I pay for my own insurance. I paid for the car by myself. That’s what makes the car mine. If it breaks down, it is my problem. If something happens to it, I have to fix it. It’s completely my responsibility, and that’s what makes it mine,” Tristan said. “I have to treat my things with respect because at the end of the day, if something happens to them, I will have to pay.”

![Keep the New Gloves: Fighter Safety Is Non-Negotiable [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/ufcglovescolumncover-1200x471.png)

![Review: “Transformers One” is a refreshing and exciting addition to the franchise [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/unnamed-3.png)

![Review: “Journals” is the gift that keeps on giving [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/monkey.jpg)

![Review: “Sonic 3” does everything great from the past two movies, and arguably even better [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/unnamed-2-812x1200.png)

![Review: Who should have really won season 33 of "Dancing with the Stars"? [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Dancing-with-the-Stars-Photo-1200x657.png)

![Review: "Wicked" is a worthy adaptation of a legendary musical [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Screenshot-2024-12-23-at-6.00.53 PM-1200x793.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)