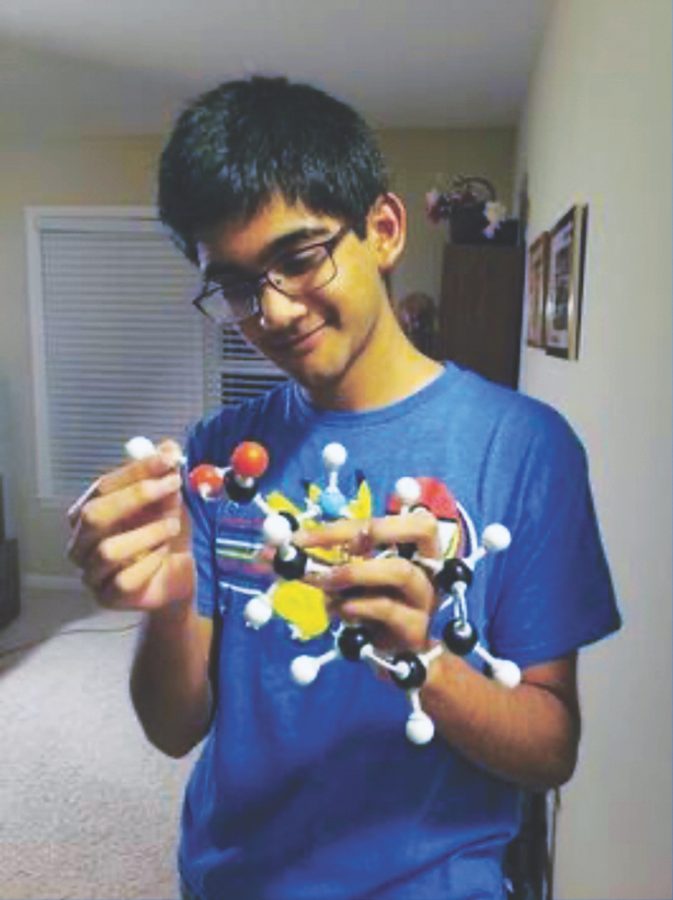

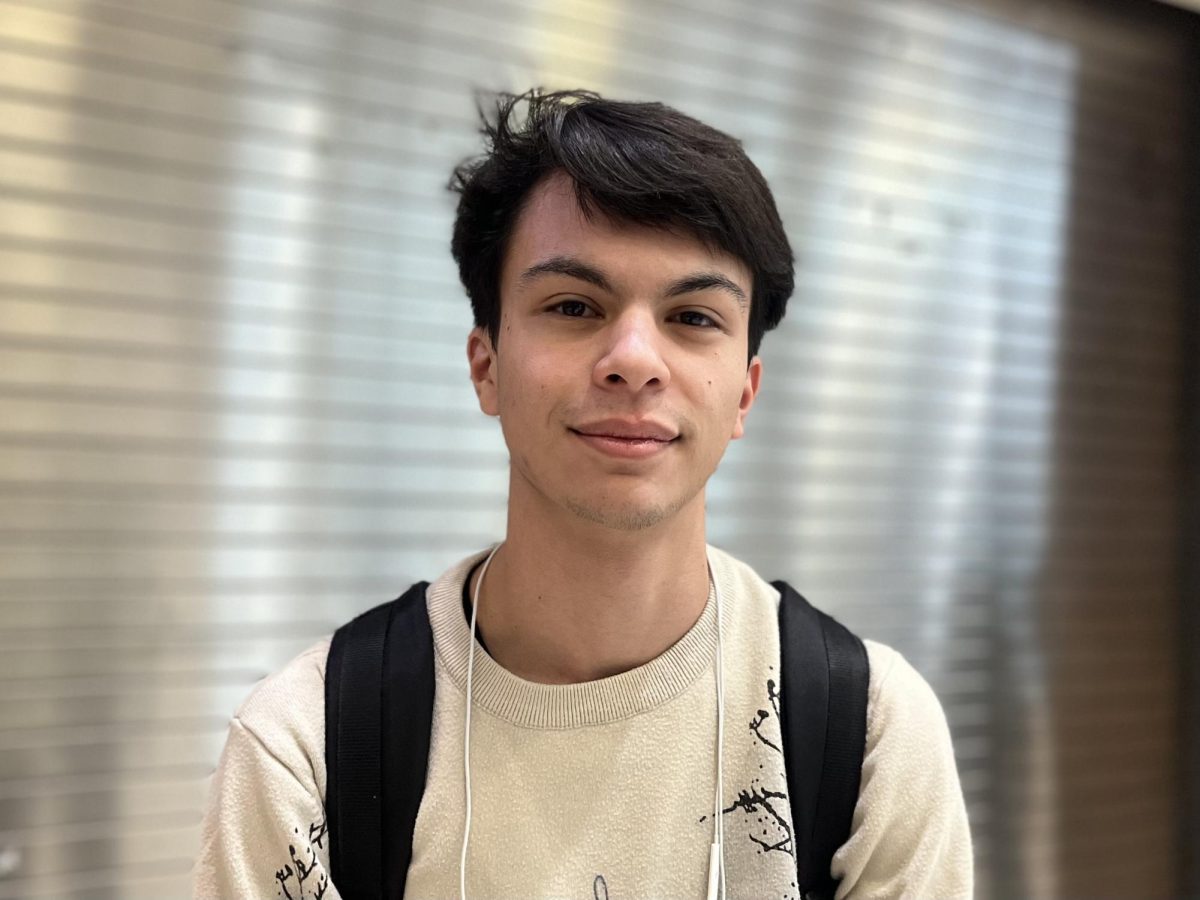

Religion and science are both important aspects of junior Labeeb Hossain’s life that go hand-in-hand.

“I think (religion and science) are pretty complementary–they kind of work with each other in a lot of ways. There are certain contradictions I can see in some places, but for the most part, I think they work together,” Hossain said. “Science really complements religion, because of how complex everything is in the universe, and it kind of makes it hard to think of everything happening spontaneously or randomly.”

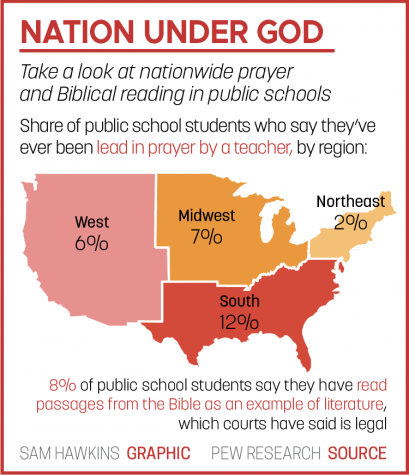

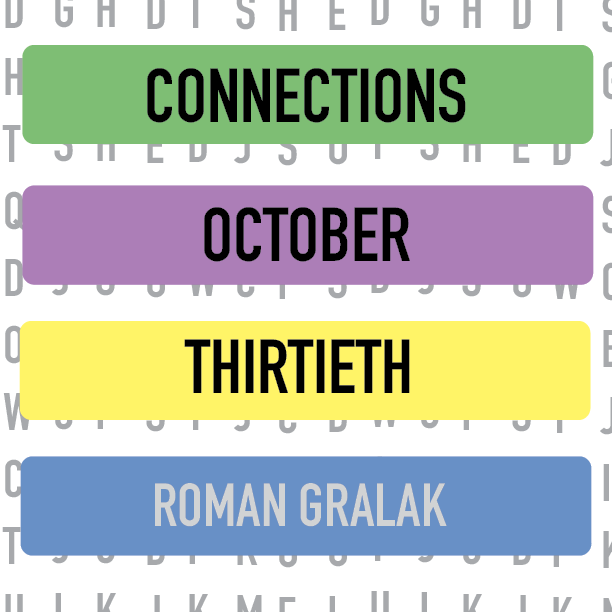

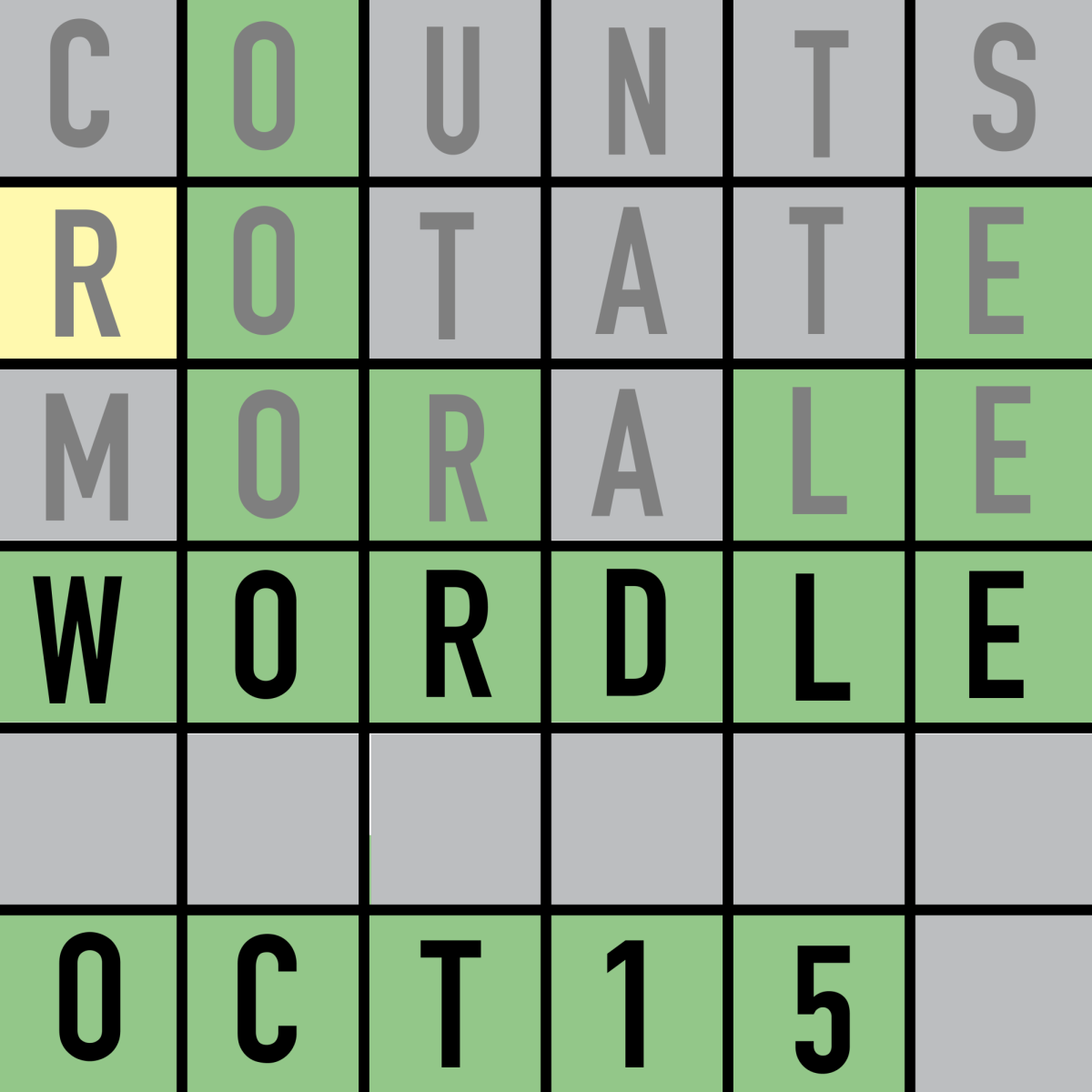

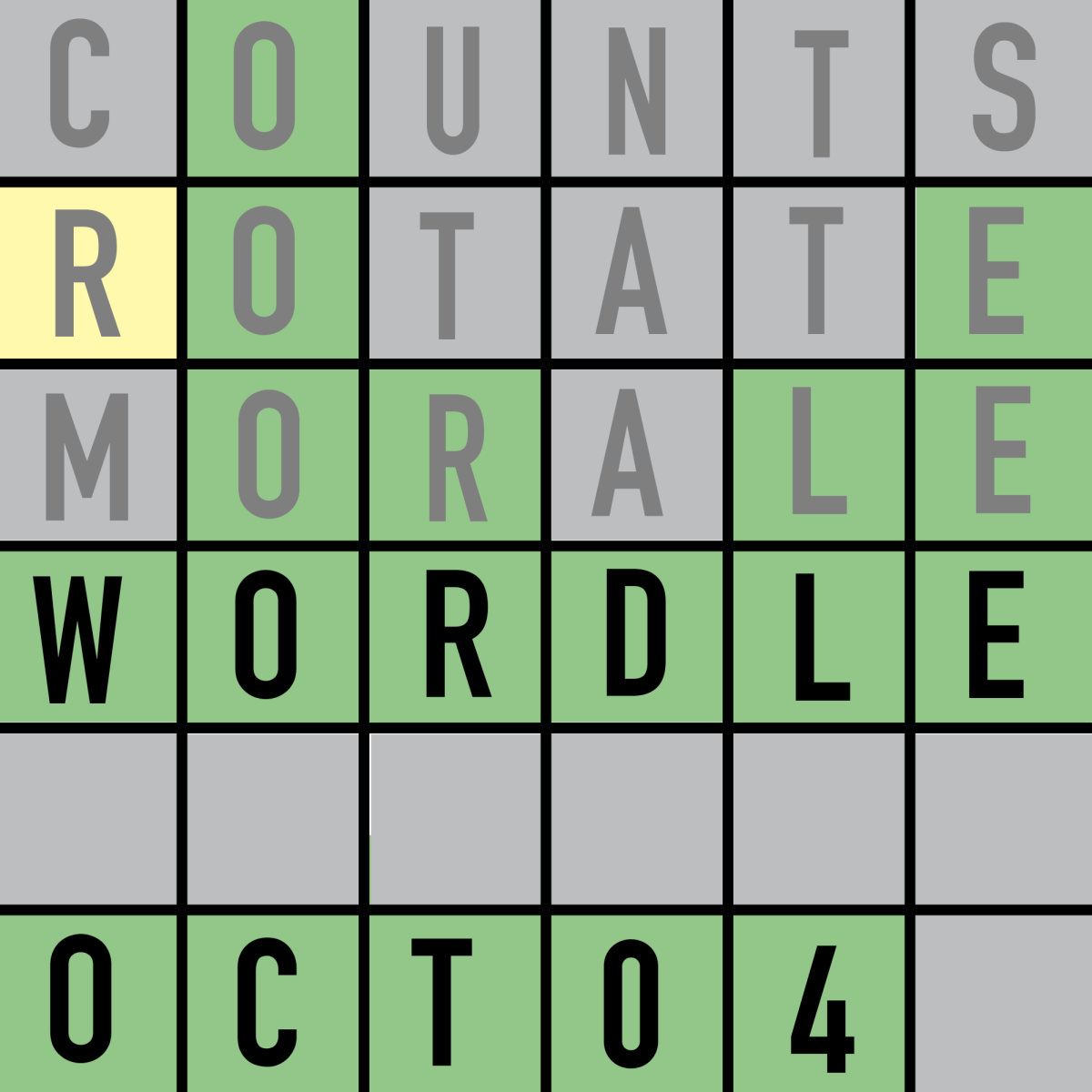

Hossain is one of many students who consider religion an important part of their daily routine. An October 2019 study from the Pew Research Center found that 53% of teenagers in the country have seen students at their school participate in some form of religious expression.

Hossain is one of many students who consider religion an important part of their daily routine. An October 2019 study from the Pew Research Center found that 53% of teenagers in the country have seen students at their school participate in some form of religious expression.

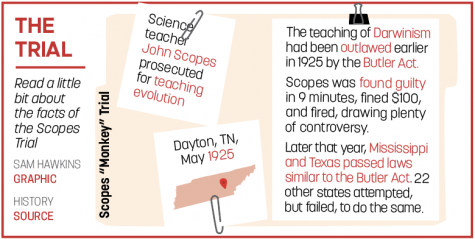

Hossain’s opinion on the complementarity of religion and science is a dramatic turn from much of the controversy of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species—which just had its 161st anniversary of publication in late November—and the Scopes Trial of 1925, when Tennessean teacher John Scopes was tried in court for teaching evolution to high school students. According to U.S. History teacher Allison Hargrove, the Scopes Trial was a high point of religion-versus-science tensions in 20th century America.

“As more and more emphasis was placed upon science in academia, as well as scientific thought and mythology, evolutionary theory became something that many universities began to teach alongside Creationism,” Hargrove said via email. “This led to many cultural wars, including- and most notably- the Scopes trial of the 1920s.”

“(Scopes) was challenging the idea that the government had the right to dictate what was taught in an academic classroom. As time progresses, what has become debated are the “gray areas”- do individual religious beliefs override individual freedoms? For example, there have been noted cases where parents of sick children who do not believe in seeking medical care fight with the government about forced interventions,” Hargrove said.

Hossain said he believes there has been considerable change since the era of the Scopes Trial, but said religion is still prioritized over science in some countries.

“In the United States, a lot of people whose parents immigrated here, and who were born here, don’t have a big problem, but one of my cousins came here from Bangladesh in seventh grade, and they never learned about evolution–ever–until they came here. So obviously, you can see they don’t teach evolution where he came from, probably because of religious reasons, but I think it’s a lot better for students who were born in the United States.”

Sophomore Avinash Valuveri said he agreed.

“I think it’s changed a lot, because society is a lot more secular, at least in our country. There’s a lot more diversity. In (some) other countries, there’s still a lot of religion in government,” Valuveri said, “But science is more acceptable nowadays, there’s more education in science in public schools, and more and more people are leaning towards science than religious beliefs.”

Valuveri, who said he used to be religious but is not anymore, said he tends to prioritize scientific discoveries over any type of spiritual belief.

“I feel like more people nowadays are believing in science than in previous generations,” he said. “I know a lot of religious people disagree with (certain scientific topics like) evolution, but last year, in our honors Biology I course, we had an entire unit on evolution, so I think it’s a lot more secular nowadays.”

Hargrove said that the conflicts between religious and scientific beliefs have had varying implications throughout history, especially depending on who was perpetrating the conflict.

Hargrove said that the conflicts between religious and scientific beliefs have had varying implications throughout history, especially depending on who was perpetrating the conflict.

“Even though religious freedom was a protected right from the onset of our nation, there have been ongoing misunderstandings about what this means because of differences in interpretation,” Hargrove said. “However, where science started to truly challenge religion was in the post-Civil War era. Specifically, the rise of Darwin’s theory on evolution caused many people to question their beliefs about Creationism, and thus, many of their vested, personal views on religion.”

Hossain said he thinks the rift between religion and science will eventually heal, even though arguments against particular sides remain.

“I think the polarizations are overblown to an extent,” he said. “The majority of people are willing to compromise, but the people that aren’t willing to compromise are a lot more vocal about it. I think there’ll be interconnectedness in the future between religion and science.

“Most religious people are open to change. They want to compromise and add sciences to their beliefs, so it’s not very polarizing for all the people that I know.”

However, Hossain acknowledges there might be some conflicts in the near future, especially with new biotechnology techniques such as gene editing.

“Gene editing is kind of a thing that I feel a lot of religious people are against, just because it’s going against how ‘God made you, and God made you perfectly, so why would you edit your genome?’ and stuff like that. I feel like that’ll be a big problem in the future–I don’t think it’s as big right now, but it’ll be a big problem in the future,” he said. “As for other fields of science, I don’t think there are any ( points of contention) other than a few biological issues. Evolution’s a big one, I think,” he said.

In Hargrove’s view, the controversies will likely continue oscillating between severe disputes to extreme similarities.

“As society’s values shift and change, so does the emphasis placed upon science and religion. It’s an ebb and flow, one that is constantly at strife, but the intensity of this strife varies based upon the challenges of the time.”

![Keep the New Gloves: Fighter Safety Is Non-Negotiable [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/ufcglovescolumncover-1200x471.png)

![Review: “We Live in Time” leaves you wanting more [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_6358.jpg)

![Review: The premise of "Culinary Class Wars" is refreshingly unique and deserving of more attention [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/MUSE-class-wars-cover-2.png)

![Introducing: "The Muses Who Stole Christmas," a collection of reviews for you to follow through winter [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/winter-muse-4.gif)

![Review: "Meet Me Next Christmas" is a cheesy and predictable watch, but it was worth every minute [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/AAAAQVfRG2gwEuLhXTGm3856HuX2MTNs31Ok7fGgIVCoZbyeugVs1F4DZs-DgP0XadTDrnXHlbQo4DerjRXand9H1JKPM06cENmLl2RsINud2DMqIHzpXFS2n4zOkL3dr5m5i0nIVb3Cu3ataT_W2zGeDAJNd_E-1200x884.jpg)

![Review: "Gilmore Girls", the perfect fall show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/gilmore-girls.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)