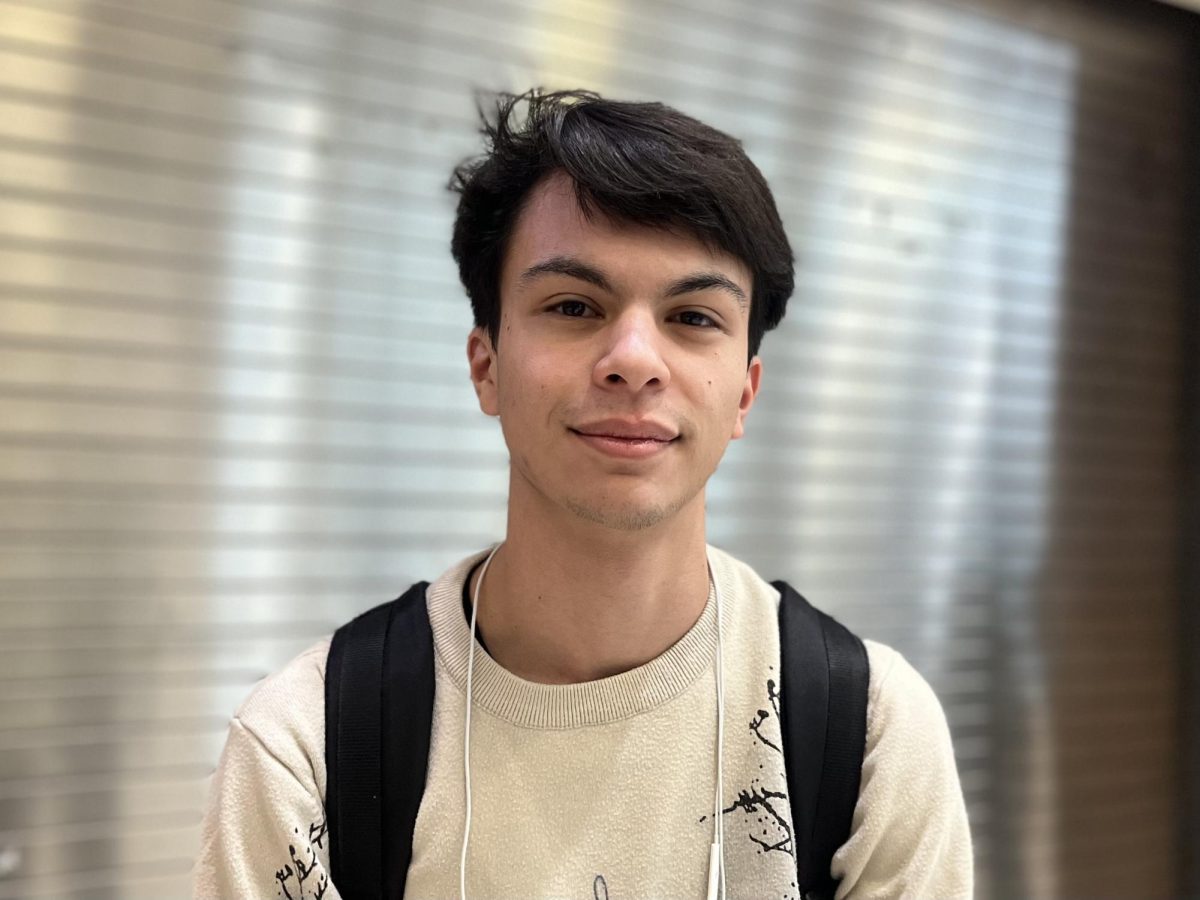

“I have cancer” are three words senior Tara Corra never expected to hear from her mother. Tara said the first sign of cancer appeared when she was at her grandfather’s home.

She said, “My mom was laying down, and I was being a little kid and was jumping near her and then I landed on her. She felt a sharp pain in her breast and it took her forever but then she was like, ‘Oh, I need to go to the doctor.’ And so she went to the doctor and it came back as (Stage 4 breast) cancer.

“Then, we moved to Indiana because of (the) good healthcare at IU (Health),” she added. “She got her help. She did chemo for a few years—I was literally in kindergarten—it’s been like my whole life unfortunately. She did all the chemo and then she beat it.”

However, while in remission, Tara’s mother’s cancer returned and this time it was far more severe.

“It metastasized. So it went from her breasts—she had breast cancer— to her liver and then to her brain, and then it was kind of just a downhill spiral from there,” Tara said. “The second time she got it she was told that she had two weeks to live and she ended up lasting another, like, three years. So she was very strong and a fighter.”

Tara’s experience is not unique. According to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, almost 3 million children in the United States have a parent who has or once had cancer. In fact, one in five newly diagnosed adults have children under the age of 18.

In 2000, the Union for International Cancer Control created World Cancer Day on Feb. 4, which this year is Feb. 4, to raise awareness of how cancer impacts everyone, including children of parents with cancer. For example, a 2017 study by Anticancer Research, found that children of a parent with cancer are more likely to have emotional problems due to shifting of household roles and changes in daily routine.

With her mom having cancer since she was young, Tara said she learned to do things uncommon for others her age.

“I had to grow and do a lot of things that other kids my age didn’t have to do,” she said. “(I had to be) in elementary school and sit in my class thinking about having to cook dinner and worry about so many things. It just made me a lot more mature and appreciative.”

Meaghan Wiggins, clinical hospital coordinator at Cancer Support Community, said it is common for children (like Tara) with parent(s) who have cancer to often take on extra burdens.

“(Kids often) shut down a little bit emotionally because they may be feeling like they have to compensate or do more roles so there isn’t that extra pressure on top of their parents—trying not to feel so much like a burden,” Wiggins said. “It’s not abnormal to get to that point of reminding the kids, you know, this is your intended role; you don’t need to work outside of that. You still need to let mom and dad be mom and dad.”

Tara said it was hard not having other people who were able to relate to her.

“I remember it was during my choir performance in eighth grade and my mom had to sit on the end-aisle chair so she could get wheeled out in case she had to throw up. Nobody else had to do that,” Tara said. “I just remember feeling so sad like nobody else has to do this and I was mad and I was angry and that’s okay. I just want people to know that every single feeling you’re feeling is valid.”

Still, despite all the challenges, Tara said her mom tried her hardest to give her siblings a normal life.

“I don’t think I missed out. My mom pushed herself to be able to let me have a normal life,” she said. “She would get me to go to the gym or the Monon (Center). She would go out of her way and drive me there; it didn’t matter how sick she was feeling. It was just different. I had a good childhood despite my mom and seeing her go through that. I was raised right and raised strong.”

Like Tara’s mom, Tara’s father John Corra said he made it a priority to be there for Tara and her siblings.

He said via email, “The treatments made it so (my wife) couldn’t do a lot of what she liked, but I tried to do more. I made the kids a priority over work and attended every event I could—sometimes with my wife and sometimes by myself. This became more so as the cancer spread.”

Mr. Corra said he and his wife made sure to stay positive around their children although it was not always easy.

“After defying the odds and being told she was in remission after the first year and the couple of years before it came back, we tried to be as normal as positive,” he said. “It was difficult at times to be positive. The type of cancer she had at the time had a 98% mortality rate if it metastasized. That was always in the back of our minds. (But) even when she was in the hospital (during her) last year, she was positive. I struggled and faked it in front of the kids.”

Mr. Corra’s experience is not abnormal. Wiggins said parents often aren’t open about their feelings on the situation.

“A lot of the time, mostly when I work with the parents, I have to remind them that it’s OK to name those feelings and to be open and to be vulnerable to help ease it for their kiddos,” Wiggins said. “Sometimes, they might not have the words for how they feel. But sometimes it does help to see, ‘Oh mom is really frustrated by this, oh I am really frustrated by this.’ It can help them connect on that deeper level.”

Tara said a lot of the changes to her life and daily activities became normalized over time.

She said, “We had to add a bunch of railings, non-slip things—we had to modify our house. We had to get puke buckets in the car, puke buckets upstairs, puke buckets everywhere. It was kind of just everywhere, like you couldn’t escape it, and it was really hard. But again, it was my entire life so it was kind of like my normal, especially with (seeing my mom with cancer) from such a young age to my freshman year all dealing with that. I don’t remember a time when she didn’t have cancer, like, it’s just been my whole life.”

Tara said the hardest part of being a child of a parent with cancer was seeing her mom during the last year of her life in 2019.

“It’s just indescribable, watching your mom thin out (and) slowly lose herself. Her eyes were sunken in; she wasn’t the same person,” she said. “That’s the hardest part. (It’s) watching this woman in hospice sitting on her deathbed and not seeing the woman who raised me until a year and a half ago. Probably (for) that entire (year of) 2019 from June to November, she was in hospice, and we spent all the birthdays there and watched her forget who we were. It was hard to watch her become this person I didn’t know anymore, and I became sort of scared to see her.

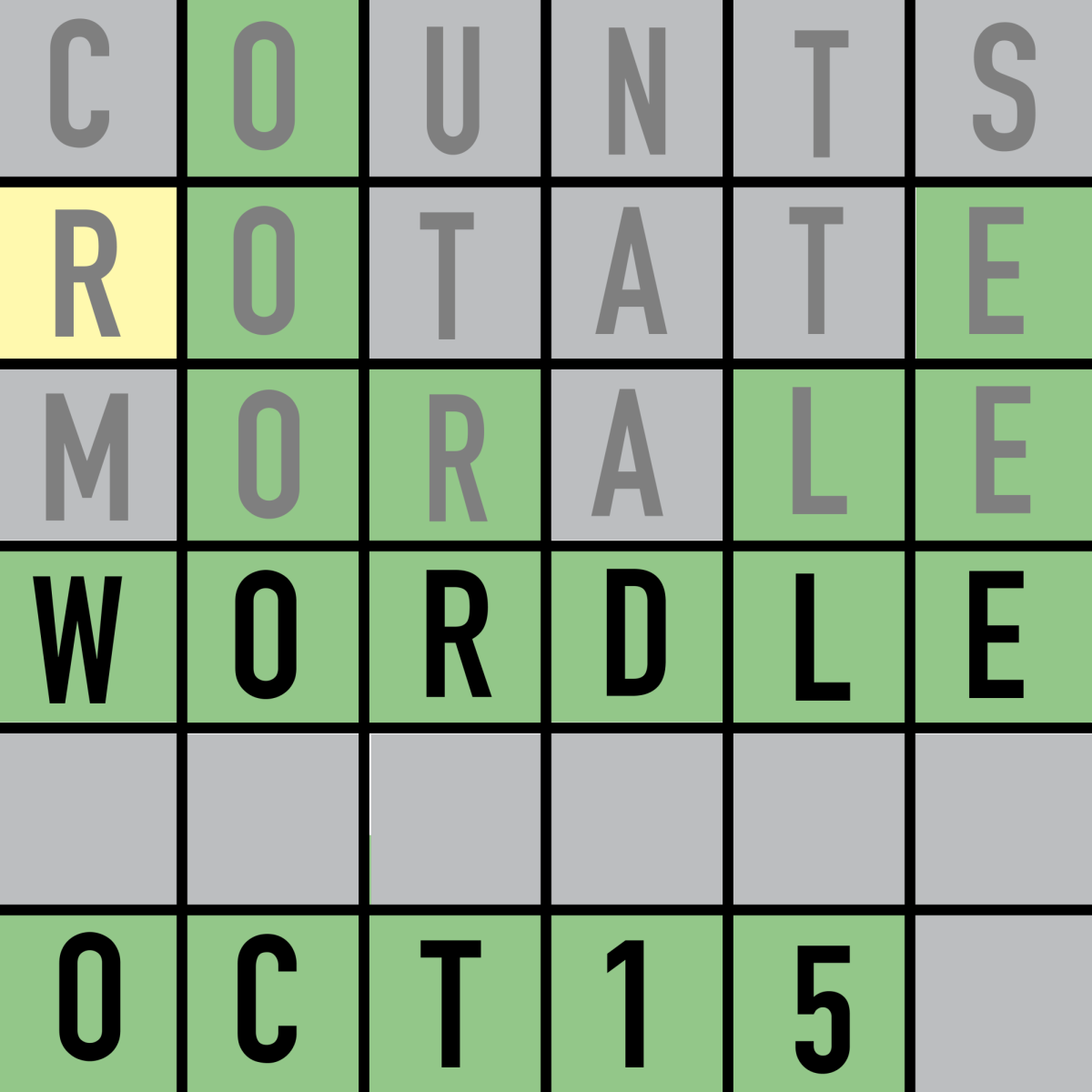

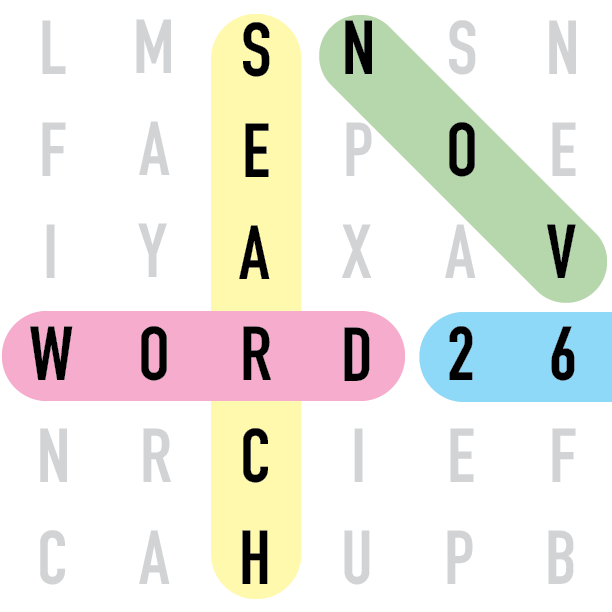

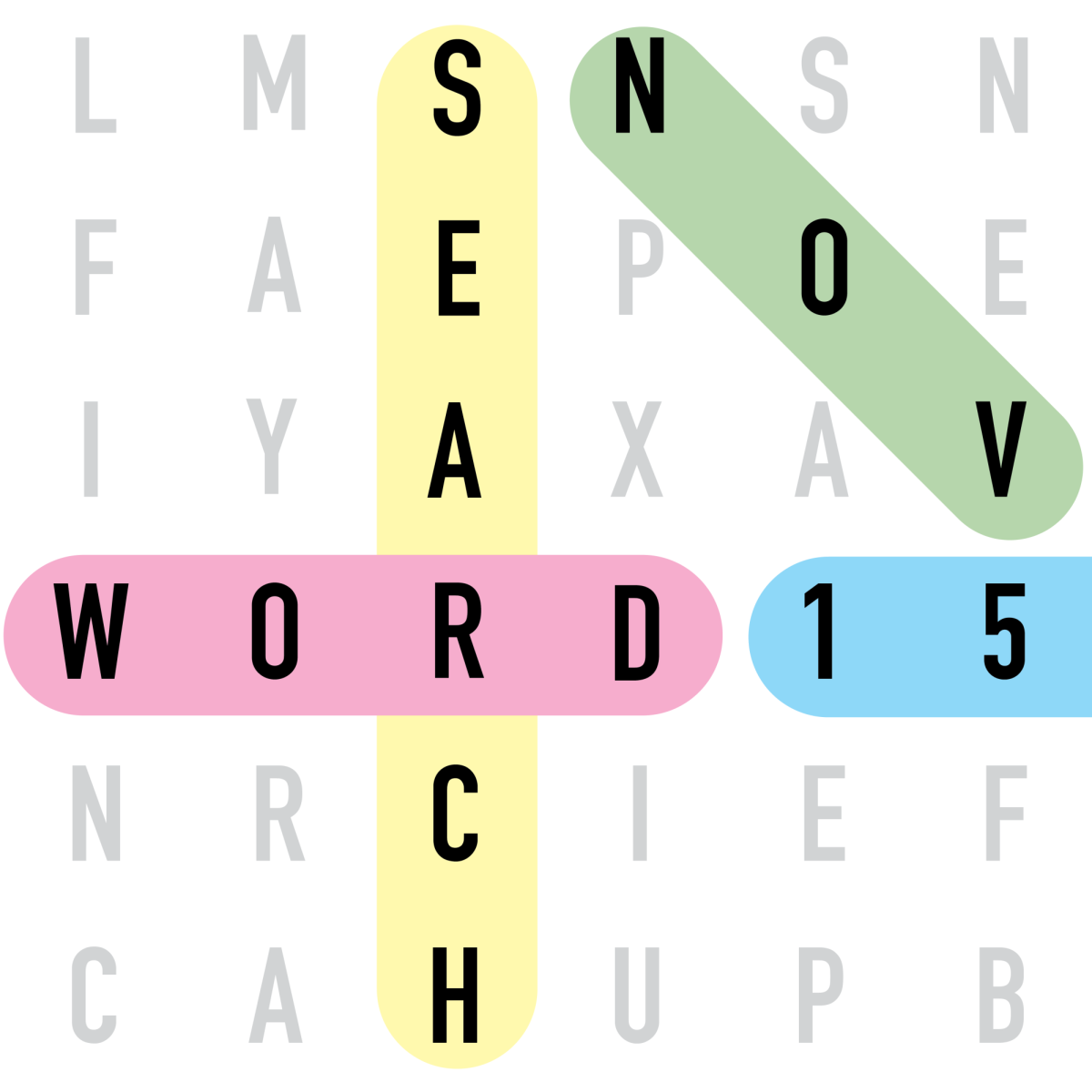

“My dad finally made us go (see her), and this was like November, and she passed away on Nov. 17, 2019,” she added. “This was like Nov. 16 or 15 (when) he made us go because I didn’t want to go because I didn’t want to see her. I kind of hold a little bit of regret about that.”

She said her family was on the way to a Colts game when her mom died.

“We were on the highway and (my dad) got a phone call and ignored it because he was driving, so he didn’t want to pick it up if it was that call. We were on our way to a Colts game, and I was pretty excited because I’d never been to one before,” Tara said. “We were in the parking garage (when we) got the phone call, started crying and got back in the car to go back.”

Mr. Corra said the biggest impact on him was his wife’s passing.

“After she passed, the biggest impact is that every milestone is bittersweet for all of us not having her there,” Mr. Corra said. “It is actually difficult to type this. She wasn’t there for my son’s college graduation, my middle child’s high school graduation, and she will not be there when my youngest (Tara) graduates high school this year.

“The biggest impact is the hole left by her not being here. I try to be the best father I can, but I believe that I will never compensate for her being gone. We will never get over losing her. No child should lose a parent like that.”

Tara said it is the small moments where she misses her mom the most.

She said, “The hard days aren’t her birthday or Christmas. Like obviously I missed her (on those days), but then I was driving one day and one of her favorite songs came on the radio, and I just had to pull over and stop and just sit in the car. I don’t know, I just sit there and think about it. I know she was suffering a lot, so I just kind of deal with it (knowing that) this is what was intended to happen and my family came out closer (and) we came out stronger.”

Mr. Corra said he agreed with Tara, and their family became closer.

“It is very difficult to see my children miss their mother. My life has focused on being there for them and making sure they have or had everything they need,” he said. “(But, having them by my side) made it easier for me to be honest. I don’t want to think about going through the loss of my wife without them.”

Tara said after her mom passed, she is able to realize what is truly important in her life.

She said, “We would argue a lot in our house (because) there were so many factors—medical bills, her throwing up, already having this really stressful thing, having these regular family arguments, and it was just all building on top of each other. But then after my mom passed, I think we were all a little quiet and a little sad and you sit there and reflect. Some of these arguments and things we were getting mad about literally don’t matter.

“I am able to look at the small things in life and realize what’s important and what’s not. I don’t stress over school as much anymore. In middle school, I would cry over my grades. Ever since my mom passed, I literally don’t care. There’s so many things that don’t matter.”

Ultimately, Tara said she hopes to help other people with her story.

“I’m willing to share because that’s how people learn,” she said. “You have to share stories, you have to be willing to go out there and speak on it for change to be made, for people to be heard and all of that stuff. I didn’t go through all that for nothing.

“If somebody’s reading this and they just want to talk or anything or have questions, I am here. The feeling of nobody understanding what I was going through when I was going through it sucked,” she said. “I just remember feeling so sad (that) nobody else has to do this and I was mad and I was angry and that’s okay. I just want (other) people (going through something similar) to know that every single feeling you’re feeling is valid.”

To read more about recent updates in breast cancer research, click here.

This is the first of three parts for this story. The second part will center those who are genetically prone to some cancers to take additional precautionary measures. Read the second part here.

![Keep the New Gloves: Fighter Safety Is Non-Negotiable [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/ufcglovescolumncover-1200x471.png)

![Review: “We Live in Time” leaves you wanting more [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_6358.jpg)

![Review: The premise of "Culinary Class Wars" is refreshingly unique and deserving of more attention [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/MUSE-class-wars-cover-2.png)

![Introducing: "The Muses Who Stole Christmas," a collection of reviews for you to follow through winter [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/winter-muse-4.gif)

![Review: "Meet Me Next Christmas" is a cheesy and predictable watch, but it was worth every minute [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/AAAAQVfRG2gwEuLhXTGm3856HuX2MTNs31Ok7fGgIVCoZbyeugVs1F4DZs-DgP0XadTDrnXHlbQo4DerjRXand9H1JKPM06cENmLl2RsINud2DMqIHzpXFS2n4zOkL3dr5m5i0nIVb3Cu3ataT_W2zGeDAJNd_E-1200x884.jpg)

![Review: "Gilmore Girls", the perfect fall show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/gilmore-girls.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)