At three months old, senior Emily Hahn was abandoned in a cornfield in southern China. At 18 months old, she was adopted by her parents, Lynne Hahn and Paul Hahn, and flew on a plane to the U.S. Emily is transracially adopted, which means her adoptive parents are a different race or ethnic group than her.

“(When I tell people) I’m adopted, most of the time (they’re) just like, “Oh, I didn’t know that because they automatically assume that I have Asian parents. Most of the time there usually isn’t any backlash (but) it’s just a bit of a shock to them,” Emily said. “When we are out in public, people won’t associate me with my parents. They’ll assume I’m with some other family nearby that is Asian.”

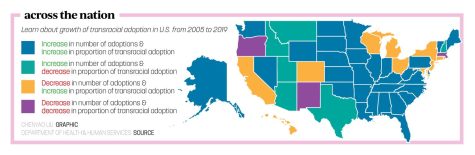

Emily is one of many individuals who have been adopted by parents of a different race. Transracial adoption has become increasingly common in the U.S. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, 29% of kindergarteners were adopted transracially in 1999. By 2011, that percentage increased to 44%. To shed light on the need for adoptive families, in 1995, President Bill Clinton declared November as National Adoption Month.

According to counselor Ann Boldt, who adopted her daughter Alyssa from China, people often disregard the complex nature of transracial adoption.

“(Some people think) that adoption is the best alternative to an abortion. Whether you’re pro-choice or pro-life, the people who say, ‘Well, you can just adopt’ don’t realize that there’s many other things that can be painful for a family that chooses adoption,” Boldt said. “To give a baby up (for adoption), is really hard, right? To be an adoptee can be very hard…They’ve lost a biological family. For a transracial adoptee, they’ve lost a culture. Studies have shown that adoptees struggle with significantly more mental health challenges compared to their non-adopted peers.

“Even though Alyssa would say that she’s in a very happy home, she feels very blessed (and) she feels very connected with us, that doesn’t mean she doesn’t feel some loss and wonder about her biological family.”

To minimize the sense of loss of culture for Alyssa, Boldt said she has made an effort to help her daughter connect with Chinese culture. Along those lines, Emily’s mother Lynne Hahn said their family also exposed Emily to Chinese culture at a young age.

“We attend festivals, attempt to make Chinese food, have made friends with the people at our favorite Chinese take-out, and even joined a girl scout troop for girls adopted from China when she was younger,” Mrs. Hahn said. “As she got older, we let her lead the way.”

Like Mrs. Hahn, Boldt said she let her daughter decide whether she wanted to continue to explore her Chinese heritage or not.

Boldt said, “My philosophy would be yes, you’d want to embrace the culture your adopted child came from for sure. And then leave it up to them, and even Alyssa was telling me how she does have regrets that she didn’t take advantage of some of the things I had provided but I (still) left it up to her (to decide what she wanted to do). I now understand that this is a common experience among transracial adoptees—a disconnect from their culture. Alyssa had internalized a lot of issues I wasn’t aware of, including trauma associated with her adoption; now, as a college student, Alyssa has described to me the experience of ‘coming out of the fog,’ and she is more fully embracing who she is as an Asian-American.”

However, not all parents do the same. In a study on transracial adoption, 56.5% of participants said their parents did not place emphasis on learning their birth culture. Moreover, some adoptees, like sophomore Anuj Gupta, said they do not feel the need to connect with the culture of the country from which they were adopted. For example, the study also found that 38.7% of participants said their parents placed “just the right amount” of emphasis on learning the heritage of their birth country, which is the case for Anuj. At 18 months, Anuj was adopted from an orphanage in India.

“My dad (is) Indian so (I connect with Indian culture) a little bit but not that much,” Anuj said. “Like when my whole family celebrates Diwali, we do that and that’s fun, but we don’t extend it to the extent that people who do practice the culture daily would. I think the extent of it right now is good. I don’t really have any interest to really expand on that because I just feel like I’ve always known what I know and I’m comfortable with that.”

Emily said she agreed with Anuj about the limited extent of exposure to her birth culture.

“I go back to (how I’m) whitewashed because it’s just factually true in my opinion because I am not exposed to the culture that somebody in China would have. In China, it’s definitely different (with) what they eat and how they work,” Emily said. “The most that my parents could do was do their best to get me to want to understand or learn more about my culture by saying, ‘Hey, this is where you’re from and this is what your culture is well-known for.’ That was just the most that they could do.”

Still, despite the limited extent of culture that the adoptee can be exposed to, Boldt, Anuj’s mom Christine Gupta and Mrs. Hahn said they believe the culture of the country from which the child was adopted should be taught and embraced.

Boldt said, “I do think it’s a responsibility of the parents to teach, embrace, and celebrate the culture of a child being adopted from another culture or country in order to provide opportunities for them to fully appreciate their heritage.”

This is the first of three parts for this story. The second part will center around transracial adoptees and their interest in finding their biological parents. Read the second part here.

![Keep the New Gloves: Fighter Safety Is Non-Negotiable [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/ufcglovescolumncover-1200x471.png)

!["Wicked" poster controversy sparks a debate about the importance of accuracy versus artistic freedom [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/riva-perspective-cover-1200x471.jpg)

![Review: “We Live in Time” leaves you wanting more [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_6358.jpg)

![Review: The premise of "Culinary Class Wars" is refreshingly unique and deserving of more attention [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/MUSE-class-wars-cover-2.png)

![Introducing: "The Muses Who Stole Christmas," a collection of reviews for you to follow through winter [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/winter-muse-4.gif)

![Review: "Meet Me Next Christmas" is a cheesy and predictable watch, but it was worth every minute [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/AAAAQVfRG2gwEuLhXTGm3856HuX2MTNs31Ok7fGgIVCoZbyeugVs1F4DZs-DgP0XadTDrnXHlbQo4DerjRXand9H1JKPM06cENmLl2RsINud2DMqIHzpXFS2n4zOkL3dr5m5i0nIVb3Cu3ataT_W2zGeDAJNd_E-1200x884.jpg)

![Review: "Gilmore Girls", the perfect fall show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/gilmore-girls.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)