In recent years, increasing pressure has been placed on Hollywood studios to deliver more films from immigrant and minority perspectives. Although this has produced a myriad of nuanced movies that promote diversity and succeed in educating audiences, this call for diversity has led to an equal rise of cookie-cutter immigrant stories that are not only unoriginal but often feed dangerous, two-dimensional stereotypes about immigrant families. And unfortunately, “Turning Red” is no exception.

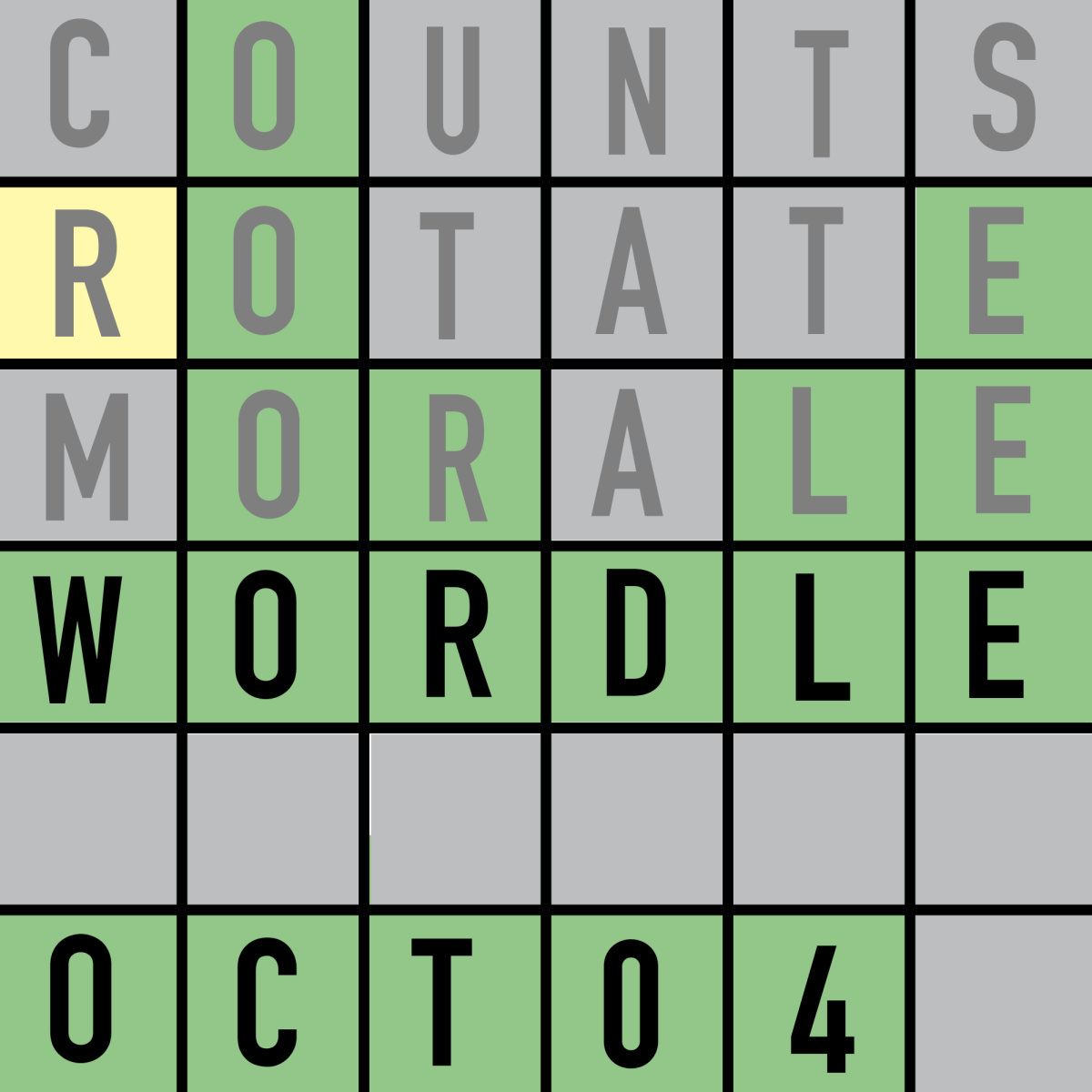

“Turning Red ” follows 13-year-old Meilin Lee, a typical teenage girl, and her relationship with her stereotypical Chinese overbearing mother. Meilin is eager to earn her mother’s validation, earning straight A’s in school and following her rules to a T, often to the dismay of her friends. Soon, Meilin is faced with her family’s curse of transforming into a red panda when her emotions become overwhelming. However, rather than fixing it, Meilin and her friends exploit her newfound superpower to raise money for tickets to their favorite boy band. This soon begins to drive a rift between Meilin’s actual personality and the persona that she lives out to appease her mother’s expectations of her. The primary conflict of the story stems from Meilin’s choice between embracing her true self or abiding by the traditional values that her family has set in place for her.

The aspect of this movie that I enjoyed the most was overwhelmingly the animation. “Turning Red” breaks free of the ongoing trend of hyperrealism and truly embraces its medium of cartoon animation. The characters’ movements and expressions are dynamic and often reminiscent of the style of emojis, which work especially well in the teenage setting of the movie. Chase scenes between Meilin and her mother are dramatized by the gravity-defying movement that fits in well with the supernatural elements of the plotline. In addition, the colors are vivid and imaginative, creating a more vibrant landscape and conveying the more mystical aspects of the movie.

However, whereas the movie succeeds in style, it fails to do the same in terms of the story itself. Immediately, the first issue I noticed about “Turning Red” was the dialogue. The interactions between Meilin and her family often feel incredibly forced. The characters often say things that are downright unrealistic or unnecessary for the sole purpose of providing more context on Meilin’s culture. Buzzwords like “ancestors” somehow worm their way into every conversation between Meilin and her family, however, despite being dropped so frequently, they are never expanded upon, which feels like a cheap attempt to pretend to educate audiences about culture without providing any information at all.

Furthermore, even when the characters do talk about their culture, they do so in a way that makes them sound more like a middle school presentation on a foreign country than an active participant in their culture. Ironically, in a movie that seeks to embrace cultural tradition, “Turning Red” manages to alienate Chinese culture even further. The movie focuses on traditional Chinese family values over other aspects of Chinese culture and portrays them as outlandish and inhumane, without ever providing insight into the benefits of these traditions. “Turning Red” villanizes familial responsibility, showcasing it as a threat to Meilin’s individualism. Her mother is portrayed first as a monster for her strict parenting style, and then upon Meilin’s discovery of her relationship with her mother, as a victim of generational trauma–the movie treats it as an utter impossibility that establishing these principles could have any possible merit. Although it is crucial to acknowledge the toxicity that can come about from traditional family values, “Turning Red” does so in a way that pays no respect to its cultural ties.

In addition, “Turning Red” does a poor job of crafting memorable and unique characters. Each one of Meilin’s friends is defined by one or two traits–Miriam is a stereotypical tomboy, Priya is dark and edgy and Abby is the affectionate and loud comedic relief. They love Meilin and boy bands, and they support her through her curse. Although I would have liked to see more character development beyond those traits, it’s completely acceptable for minor characters, especially in a kids’ movie, to have basic personalities. However, the film’s true issue with characterization lies within its portrayal of Meilin’s family, the primary antagonists of the movie. The only thing we truly learn about Meilin’s father throughout the entire story is that he can cook. Save for the single conversation that Meilin has with him where he encourages her to follow her heart, the audience never sees much of his personality or his experience with the family curse. When accounting for the influence he has on Meilin’s life, he plays a disproportionately minimal role throughout the film. However, my primary issue with “Turning Red” is the representation of Meilin’s mother. She plays the role of a stereotypical tiger mom–overbearing and overprotective over Meilin and easily becomes a very dislikable character. Despite the justification behind her behavior, her unoriginal characterization confines her to an established stereotype that sweeps the depth behind her character under the rug. Her sudden redemption, when Meilin finds out about her own feelings of inadequacy, feels underdeveloped and out of context with the rest of the film and fails to provide a satisfying conclusion to the conflict at the end of the movie.

Although I applaud “Turning Red” for its creative pursuits in style, its take on the themes of family and culture relies too heavily on established stereotypes and fails to provide a fresh outlook on these issues.

On this blog, members of the Carmel High School chapter of the Quill and Scroll International Honorary Society for High School Journalists (and the occasional guest writer) produce curations of all facets of popular culture, from TV shows to music to novels to technology. We hope our readers always leave with something new to muse over. Click here to read more from MUSE.

![Keep the New Gloves: Fighter Safety Is Non-Negotiable [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/ufcglovescolumncover-1200x471.png)

![Review: “We Live in Time” leaves you wanting more [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_6358.jpg)

![Review: The premise of "Culinary Class Wars" is refreshingly unique and deserving of more attention [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/MUSE-class-wars-cover-2.png)

![Introducing: "The Muses Who Stole Christmas," a collection of reviews for you to follow through winter [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/winter-muse-4.gif)

![Review: "Meet Me Next Christmas" is a cheesy and predictable watch, but it was worth every minute [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/AAAAQVfRG2gwEuLhXTGm3856HuX2MTNs31Ok7fGgIVCoZbyeugVs1F4DZs-DgP0XadTDrnXHlbQo4DerjRXand9H1JKPM06cENmLl2RsINud2DMqIHzpXFS2n4zOkL3dr5m5i0nIVb3Cu3ataT_W2zGeDAJNd_E-1200x884.jpg)

![Review: "Gilmore Girls", the perfect fall show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/gilmore-girls.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)

![Review: “Turning Red” is a run-of-the-mill take on an overdone trope [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Screenshot-2024-01-24-2314441-1200x675.png)