In a research lab at Purdue University, Sepehr Asgari, a student researcher and sophomore, tests the effectiveness of his combination treatment on neonatal meningitis. Just last June, Asgari began working with this rare strain of meningitis that mainly affects newborns as a result of personal interest and enjoyment.

“I personally enjoy it because I learn a lot from it, and it’s an application of what I would learn from textbooks,” Asgari said. “I don’t  enjoy just learning about what other people have done, and I like to innovate and find new things.”

enjoy just learning about what other people have done, and I like to innovate and find new things.”

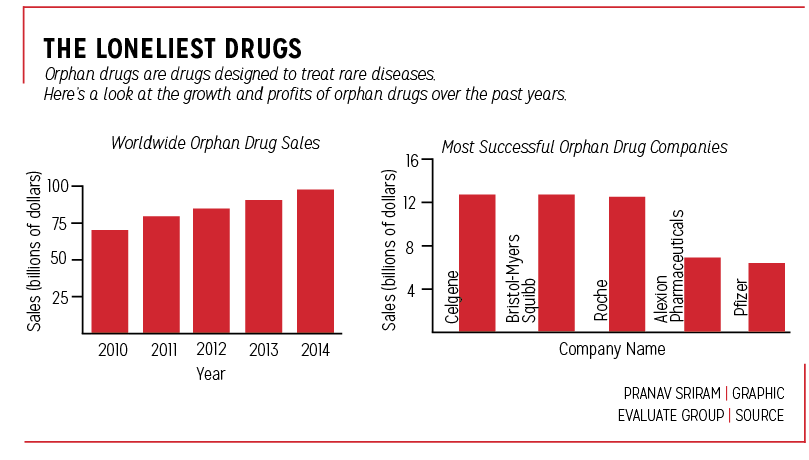

Asgari said his goal is to develop a drug that will cure this disease. The drug he is attempting to develop is classified as an “orphan” drug, a drug manufactured primarily for the treatment of a rare disease.

“The bacteria is E. coli K1, which is a specific strain (of E. coli), and it has a capsule on the outside of it, and that capsule is associated with the pathogenesis of the bacteria,” Asgari said. “My treatment is that I’m taking two proteins; one will strip the outer capsule away and that’s fused to another protein that has anti-inflammatory properties.”

Today, more and more students are beginning to work on innovations that may help patients with rare diseases. According to Satvik Kumar, injection lead of InvenTeam and sophomore, CHS InvenTeam is working to develop a device that can inject medicine into an epileptic patient, specifically children.

While epilepsy is not ordinarily classified as a rare disease, many forms of long-term epilepsy in children are classified as a rare brain disorder.

“We were looking at problems that the world faces; (we found) epilepsy to be stated as one of the main problems,” Kumar said. “The main problem is, if (patients with epilepsy) get treatment within five minutes, it helps them. But the average ambulance response time, even in the United States, is 9.4 minutes. It’s even longer in underdeveloped countries.”

According to Wendy Tian, senior director of regulatory affairs at Lundbeck, a pharmaceutical company that specializes in psychiatry, neurology and brain disorders, the United States classifies a rare disease as a disease that affects fewer than 200,000 people; one such way to treat these diseases is with orphan drugs.

Tian said, “The prevalence of patients defines whether (a drug) is an orphan or not. If the drug is an orphan drug, the government wants to encourage the developer, pharmaceutical company to study it.”

Moreover, Tian said she believes it is important that everyone, including students like those in InvenTeam, be educated on th e importance of orphan drugs and help patients with rare diseases.

e importance of orphan drugs and help patients with rare diseases.

“I think it is good for students to participate (and) to develop technology and contribute ideas in drug or medication device discovery for rare disease treatment,” Tian said. “In many ways, young people have great innovative ideas and can think out of the box, which could be converted to novel approaches to address the medical needs of patients.”

DUAL DESIGNATION

According to NPR, there have been cases where companies create orphan drugs for profit and for economic advantages on the market rather than focusing on helping patients.

In 1983, the Orphan Drug Act was signed by President Ronald Reagan, creating and ensuring a few benefits for companies developing an orphan drug such as tax deductions and market exclusivity.

Eleanor Dixon-Terry, Regulatory Health Project Manager at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), said via email, “Orphan designation qualifies the sponsor of the drug for various development incentives of the (official development assistance) ODA, including tax credits for qualified clinical testing.”

Tian said, “You will also get seven years exclusivity. After you market the drug, no one else can market the (same) drug until after you have finished seven years of marketing.”

According to a separate NPR article published this year, some pharmaceutical companies are beginning to take advantage of these benefits. Furthermore, it highlighted that some drugs were given orphan designation and regulatory status.

The FDA’s CDER Rare Disease and Orphan Drug Designated Approvals spreadsheets and NPR indicate Abbvie Inc’s HUMIRA© as one such drug. First approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in 2002, HUMIRA© later received multiple orphan designations; in 2014, it was approved for two different rare diseases, and in 2015, it was approved yet again for another rare disease.

The FDA’s CDER Rare Disease and Orphan Drug Designated Approvals spreadsheets and NPR indicate Abbvie Inc’s HUMIRA© as one such drug. First approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in 2002, HUMIRA© later received multiple orphan designations; in 2014, it was approved for two different rare diseases, and in 2015, it was approved yet again for another rare disease.

All in all, HUMIRA© has made a profit of approximately $11.8 billion worldwide last year.

Moreover, according to the same NPR article, orphan drugs have become a booming business, as orphan drug tax credits paid by the federal government totaled at $1.76 billion last year.

According to Tian, one drug can actually treat multiple diseases no matter what designation.

“Orphan drugs are not designated based on the compound; they’re designated for an indication, a disease,” Tian said.

Tian also said there is no difference in the approval process of regular and orphan drugs.

Dixon-Terry said via email, “The granting of an orphan designation request does not alter the standard regulatory requirements and process for obtaining marketing approval. Safety and effectiveness of a drug must be established through adequate and well-controlled studies.”

MOTIVATION TO INNOVATE

Asgari, however, said he understands some companies feel the need to make more money, but he still believes it is more important to really help people. “It’s in their economic interest to do that. But, sometimes you need the more human aspect,” he said.

As in the case of InvenTeam, their work also began as a result of one of their team member’s close connection to epilepsy. Cameron “Cami” Poulsen, PR lead of InvenTeam and junior, said one of her close friends was affected by epilepsy as a child.

“It’s hard to see someone in that (state) … and I think seeing that really affected me more. Epilepsy has so many triggers; one of the doctors told her she had to live life in a bubble because of how often she could get triggered by heat or any lights,” she said.

Tian said she also believes that in any case, not specifically HUMIRA©, a drug cannot be truly successful if the company is only in it for the profit.

“In my experience, I don’t think the company will be successful or work if their motivation is to only go after the profit,” Tian said. “I think if they can develop a drug and in the meantime make a profit from that development that’s great because they have the money to continue development for other drugs. But if their only motivation is money, it will be short-lived.”

In trying to actually develop a working drug, however, there are other obstacles besides moral ones that are frequently encountered.

Asgari said, “Bringing new drugs to market is a lot harder than it seems, especially medical devices… It’s very expensive to do that. I think it would be beneficial for all of society if somehow the whole process were made a whole lot more easy: shorter, cheaper and more accessible to more people.

“With research, there’s so many new concepts and applications of drugs being discovered, but they’re just not going to market because it’s not feasible for them to do that.”

OVERCOMING OBSTACLES

According to Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development, it now costs about $2.6 billion to not only create a drug but also have it approved.

Tian, however, encounters a different problem when trying to create a new drug.

“For a lot of normal drugs, you may have 1,000 patients in the clinical trial, but for orphan drugs you may have

only a couple 100, which is a big deal,” Tian said. “And some of the drugs are called ultra-orphan and you may have only a couple 100 in the whole world and only a handful of patients in the study.”

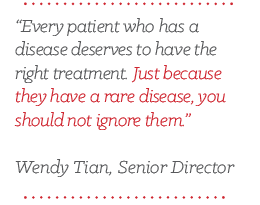

Nonetheless, Tian said she believes everyone deserves to be treated respectfully and get the right treatment for a reasonable cost. “Every patient who has a disease deserves to have the right treatment. Just because they have a rare disease, you should not ignore them,” Tian said.

Asgari said he is still hopeful in face of the many trials he may encounter.

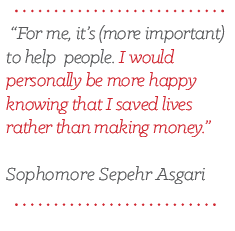

“For me, it’s (more important) to help people,” Asgari said. “I would personally be more happy knowing that I saved lives rather than making money.”

According to Tian, it is not only important to keep developing these drugs but also vital to continue educating the next generation.

“Our company has a story,” Tian said. “One day, a girl was walking on the beach, and there was a starfish on the beach. So this girl picks up the starfish and throws it to the sea. Her mom came over and asked ‘What are you doing?’ and she replied, ‘Oh, I’m putting the starfish back in the sea so the starfish can survive.’ The mom said, ‘There are so many starfish on the seashore; you cannot save them all.’ But, she says, ‘I can save this one.’

Tian continued, “The moral of the story is if you can save one patient and make a difference to their life, it’s meaningful.”

![AI in films like "The Brutalist" is convenient, but shouldn’t take priority [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/catherine-cover-1200x471.jpg)

![Review: “The Immortal Soul Salvage Yard:” A criminally underrated poetry collection [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/71cju6TvqmL._AC_UF10001000_QL80_.jpg)

![Review: "Dog Man" is Unapologetically Chaotic [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dogman-1200x700.jpg)

![Review: "Ne Zha 2": The WeChat family reunion I didn’t know I needed [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/unnamed-4.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)