Just over fifteen years ago, the young adult (YA) dystopian genre hit what many consider to be its “golden age” with the publication of the first novel of Suzanne Collins’ “The Hunger Games” (2008). The critically-acclaimed book series tells the tale of Katniss Everdeen, a teenage girl forced by the government to compete in a killing game. It was praised for its critique of the media and wealth disparity, and went on to be adapted into several movies that also shone in popularity.

The late 2000s and early 2010s saw a flood of similar stories, with series such as “The Maze Runner” (2009) and “Divergent” (2011) all following plot paths of defiant, strong-minded teens fighting against oppressive norms in a post-apocalyptic world. Perhaps what made them so appealing among young adults was the idea of people their age being able to bring real change to the world. Not only that, they addressed societal problems that, while obviously exaggerated in the stories, were perfectly relevant issues.

Still, it was clear that there would be an eventual falloff. The popular saying “too much of a good thing” might be the best way to describe YA dystopia’s decline. While “The Hunger Games,” being one of the first and most notable of its genre, brought fresh ideas and plots, the media that followed it could only be described as repetitive. Book after book followed the same predictable tropes, leading many forms of YA dystopian media to feel the same. Tom Isbell’s The Prey (2015) fell victim to that pattern, its plot following a group of teenagers escaping a cruel system imposed upon them by an oppressive government. Sound familiar? The public deemed the novel a lukewarm crossover between The Maze Runner and The Hunger Games and not worth the read.

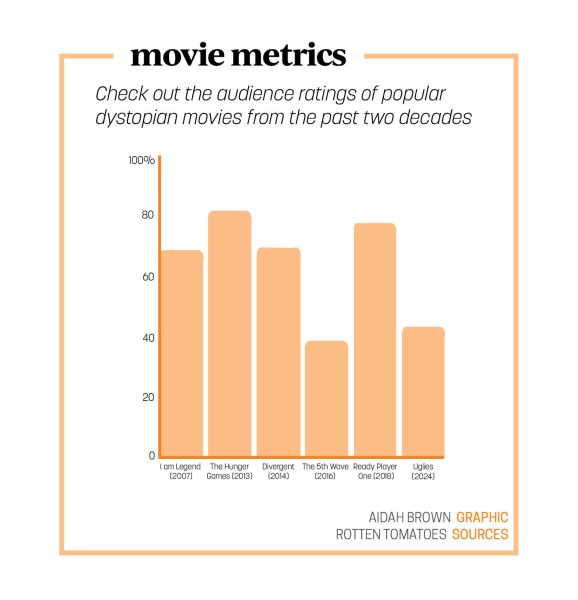

Movie remakes of beloved novels would theoretically have brought about a breath of fresh air, but a large portion of them were far from meeting viewers’ expectations. Subpar adaptations led to many of them being viewed as unfaithful to their original books. The 2005 novel Uglies by Scott Westerfield, an early piece of media of the YA dystopian genre, was generally well-met in its time, though it never rose to any notable popularity. On the other hand, its 2024 movie remake was met with strong backlash and negative responses due to questionable casting choices. It was also criticized for its deviation from the original novels, with the movie taking several creative liberties.

The movie adaptation of “Allegiant” (2016), the third book in the Divergent trilogy, was a box office flop, grossing only about $179.2 million worldwide. An especially disliked pattern of these movie remakes was the final installment being split into two parts, garnering accusations of being cheap cash grabs. Inevitably, movie remakes didn’t hold nearly enough potential to revive YA dystopia to its former glory.

Today, the genre is still nowhere near as loved or as hot of a topic of discussion as it was in the early 2010s. But this doesn’t mean that it has or should fade into obscurity. It seems like people today are still hoping and rooting for the future of YA dystopian media, because despite “Uglies’” less-than-exemplary reviews, the movie still managed Netflix’s Top 1 spot. While it is hardly possible to bring it back to exactly as it was in the past, perhaps what the genre really needs to revive is a factory reset and changing with the times might be the key to this.

First of all, reshaping old ideas to appeal to the world of today would allow for fresh and interesting new stories to be told rather than the same variations. Additionally, pushing for original YA dystopian content in the form of movies and online shows rather than traditional novels and remakes could be a huge viewing success, especially since we live in a world where television and streaming services dominate the entertainment industry. Though another “golden age” for the genre might be a far reach, it is still too early to be putting this genre in its grave with the potential it has.

The views in this column do not necessarily reflect the views of the HiLite staff. Reach Catherine Guo at cguo@hilite.org.

![AI in films like "The Brutalist" is convenient, but shouldn’t take priority [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/catherine-cover-1200x471.jpg)

![Review: “The Immortal Soul Salvage Yard:” A criminally underrated poetry collection [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/71cju6TvqmL._AC_UF10001000_QL80_.jpg)

![Review: "Dog Man" is Unapologetically Chaotic [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dogman-1200x700.jpg)

![Review: "Ne Zha 2": The WeChat family reunion I didn’t know I needed [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/unnamed-4.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)

![“Uglies” is a call for change in the YA dystopian genre [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Perspectives-Cover-1200x471.jpg)