An international test reveals the weakness of American education in mathematics and science. The country now aims to strengthen its focus on ‘STEM’ subjects.

By Kendall Harshberger

<kharshberger@hilite.org>

At 3:05 p.m., when most students at this school flood the halls and prepare to head home, junior Ryan Wilmes usually remains behind with his fellow TechHOUNDS members to build a robot.

“Monday, Wednesday and Friday, we stay from 5:30 to 9 p.m. On Tuesdays and Thursdays, we stay after school until 6:30. And then on Saturdays, we usually have meetings,” Wilmes said.

Along with being a team leader in TechHOUNDS, Wilmes is enrolled in several math and science classes including AP Physics B, AP Chemistry and AP Calculus AB, and he said he intends to take AP Calculus BC and AP Physics C next year. He doesn’t plan to stop there.

In college, Wilmes said he would like to study to become a mechanical engineer. Wilmes said his work in TechHOUNDS will be beneficial in his pursuit.

“You learn a lot (in TechHOUNDS). It’s more of like a hands-on class work,” he said. “Where in math and physics you just do the science behind it, here you can actually see how it works.”

However, recent studies imply that Wilmes may be among the minority of students in the country who are pursuing achievements in math and science, according to the test results from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), an internationally standardized test administered to 15 year-old students, released in December 2010.

American students who were tested ranked 23rd in science and 31st in math, far lower than 2006 levels.

Because of these dropping statistics, current politicians have begun to push for more success in these areas, dubbed “STEM” subjects, which stand for science, technology, engineering and math.

Math teacher Janice Mitchener, who recently traveled to Washington D.C. and met President Barack Obama for receiving the Presidential Award for Excellence in Mathematics and Science Teaching (PAEMST), said she saw several presentations on American education and its need to change, especially in regard to STEM subjects.

“I saw a chart that said, in over the last 10 or 20 years, the largest difference between the highest a country has ever ranked and the lowest a country has ever ranked belongs to the United States. We hold the record for the largest gap. That’s not a good thing at all,” she said. “I think maybe it’s time just to step it up a little bit in the United States.”

Mitchener said there may be a number of reasons for the sharp decline.

“Maybe other countries that were down lower in previous years started making some changes and improved,” she said. “As far as what happened in the United States, it’s hard to say. Maybe we just looked at our scores and thought, you know, the status quo was good and we didn’t need to make any changes, so we fell behind.”

Federal Programs to Help

Obama looks to change that disparity with a national program called Change the Equation. According to Change the Equation’s website, only 56 percent of 2010 high school graduates are ready for college math and 36 percent are prepared for college science. And those are some of the higher percentages. Mississippi, for example, has only 20 percent of its high school graduates ready for college math and 14 percent for college science.

To mend this, Change the Equation looks to create a widespread literacy in the STEM subjects. This, according to the site, will begin with improving STEM teachers, inspiring student appreciation of STEM subjects and getting the nation involved through the help of over 110 CEOs of several large companies across the board.

A similar program was adopted last year called Race To the Top. This program, according to Mitchener, would give qualifying states grant money to work on their schools.

“Indiana chose as a state to adopt common course standards and apply for (Race To the Top), but we did not qualify for it. But we still are using those common course standards,” Mitchener said.

The difference between Race To the Top and Change the Equation is mainly in STEM education.

Mitchener said, “I think the main thing to look at is that STEM education is the main focus. The big move is, how can we improve our STEM education? How can we help to get more qualified and prepared teachers in the classroom? We just need to improve those fields,”

The CEOs of several companies, some of which include Intel, Time Warner Cable, Xerox, Kodak and Sally Ride Science, joined forces with Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to form Change the Equation.

“Companies have invested interest in this because it’s the mathematicians and the scientists that come out of colleges and go into some of these companies, so of course the corporations have invested interest and funds into this project,” Mitchener said. “It’s the students that benefit from (Change the Equation) because it will help them in the future.”

As far as what schools this will affect, Mitchener says she thinks it will affect all schools, including this school.

“They’re going to be looking at all schools. If you look at Carmel High School, we’re not struggling academically as a whole school to meet our Adequate Yearly Progress or to meet our state testing, but there’s always room for improvement,” she said. “If you just sit back and think, ‘Well, we’re a great school, we don’t need to improve scores,’ you’re going to fall behind.”

Who’s Responsible?

Part of the success or failure of U.S. students in STEM subjects may come from parents, but even they don’t necessarily guarantee enrollment in STEM subjects. Senior Irene Gibson, who said that the pressure her parents placed on her in the past led her to be more self-motivated, chose to not take a math class this year. Gibson said her parents were slightly worried about her not taking a math class during her senior year at first, but did not pressure her too much to enroll in a math course.

“My dad wanted me to take math, but my mom was fine with it. When they realized there was no room for (Statistics), they were both okay with it, though,” she said via e-mail. “The only worry was that colleges looking at my classes would think I was using this year as a blow-off year, but really, I’m taking all IB classes. Also, my counselor said when she wrote to them she’d explain the situation.”

Gibson said she thinks it is the parents’ responsibility to stress the importance of academics on children.

“If done correctly, stressing the importance will cause the students to pressure themselves into performing well academically,” she said via e-mail. “In my case, both parental and personal pressure contribute to my academics.”

According to Mitchener, another aspect that could contribute to the drop in success in STEM subjects is teaching quality.

“There are some areas in our country where teacher quality is just not up to standards, and, if you think about it, that’s really not fair to the kids at that school. It’s just not,” she said.

Another issue in the world of STEM is that students just aren’t as interested in math and science anymore. According to The New York Times, participation among students in science fairs is declining rapidly. The Los Angeles science fair, one of the largest in the country, has only 185 participants this year, compared to the 244 who took part a decade ago.

Politicians are worried that with the loss of the science fair comes the loss of exposure of the scientific process to teenagers and, with that, fewer teenagers interested in STEM-related jobs. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, projecting forward from 2002 to 2012, the need for science and technology workers will increase by 26 percent compared to 15 percent for all occupations.

CHS Well Prepared

Mitchener said this school has always encouraged students to get involved in STEM subjects.

“Here we’ve always had our counselors encouraging students to take the highest math and science classes that they’re qualified for,” she said. “We are adopting a new engineering program in the Industrial Tech to encourage engineering professions, but other than that I don’t think we’re doing many other things to encourage STEM, mainly because we already are.”

According to Change the Equation’s website, in its first year it hopes to work with its member companies to begin spreading a small number of programs that work to 100 sites across the country where student performance is low. Also, it hopes to create a scorecard that can assess the condition of STEM education in all 50 states. This first scorecard will provide a baseline from which to measure states’ progress in coming years.

Mitchener said changes need to be made in education.

“Education reform, I think, is something that the Democrats and Republicans can’t really argue too much about. Just by looking at the numbers, you can see something needs to be done, especially in math and science,” she said.

As far as any changes hat this school, Assistant Principal Ronda Eshleman said they would not be remarkable.

“I don’t see dramatic changes for us,” Eshleman said. “We are adopting the new national core standards over the next three years, but I don’t think it’s going to change the way we do things a whole lot. We already have highly qualified teachers in math and science, and we’ll keep stressing the importance of those topics, but I don’t see significant changes.”

Eshleman also said this school is already doing a lot to focus on STEM classes for students.

“As a school, we feel it’s important to take rigorous science and math classes and encourage all students to do so. As colleges also see the need for this, it will become more important for students to show high levels of achievement in these areas,” she said via e-mail. “Our enrollment in our Project Lead the Way Engineering classes keeps growing each year, especially with the dual enrollment college credits student can earn from Invites and Purdue. We continually look for ways to integrate technology into all our courses.”

Wilmes said he thinks math and science are especially important subjects.

“What you learn in math and science, you can use in almost any job and on a daily basis. It’s really important,” he said. “From high school, you see a lot of kids who ask, ‘Well, why does it do that?’ but they don’t have the curiosity to see why it works. They just go through life accepting what it is without knowing why it is, but knowing the reason why can be really important.”

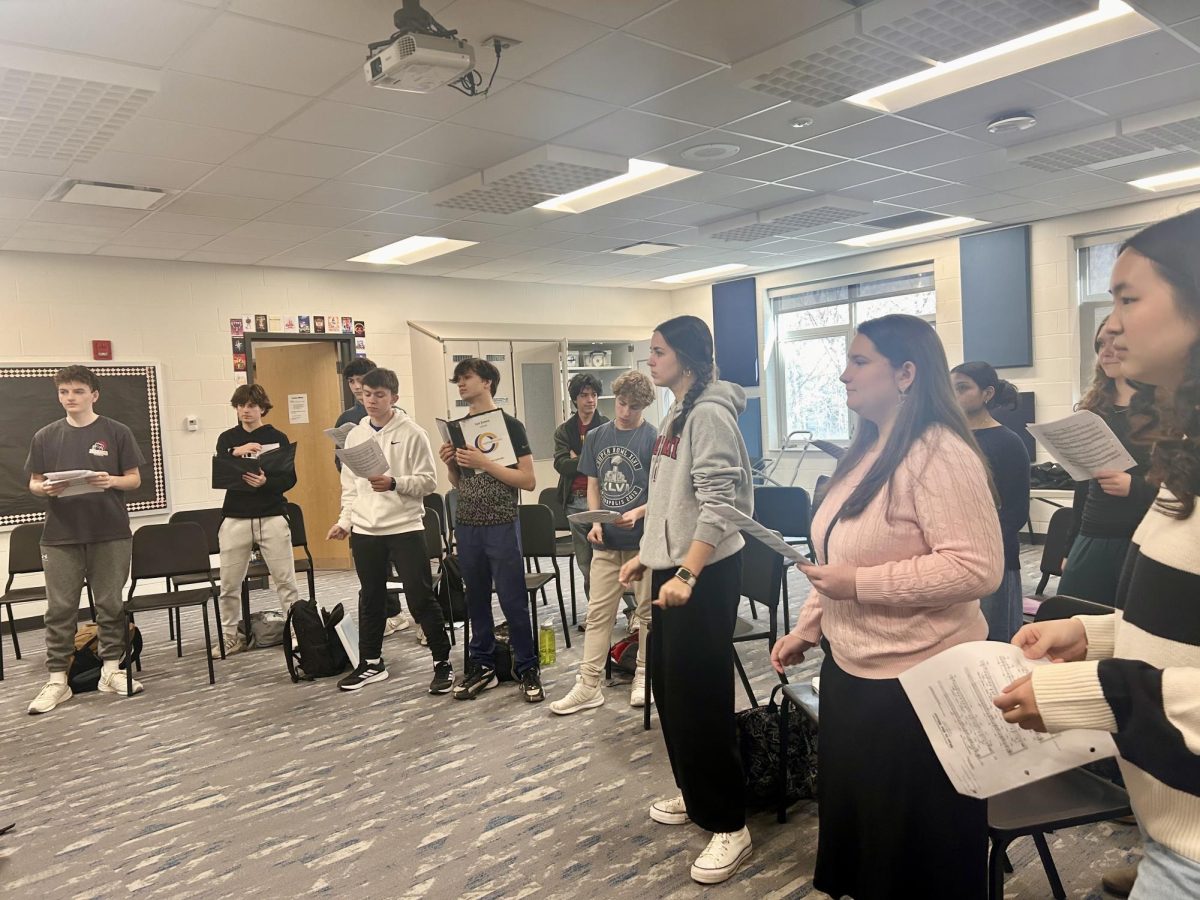

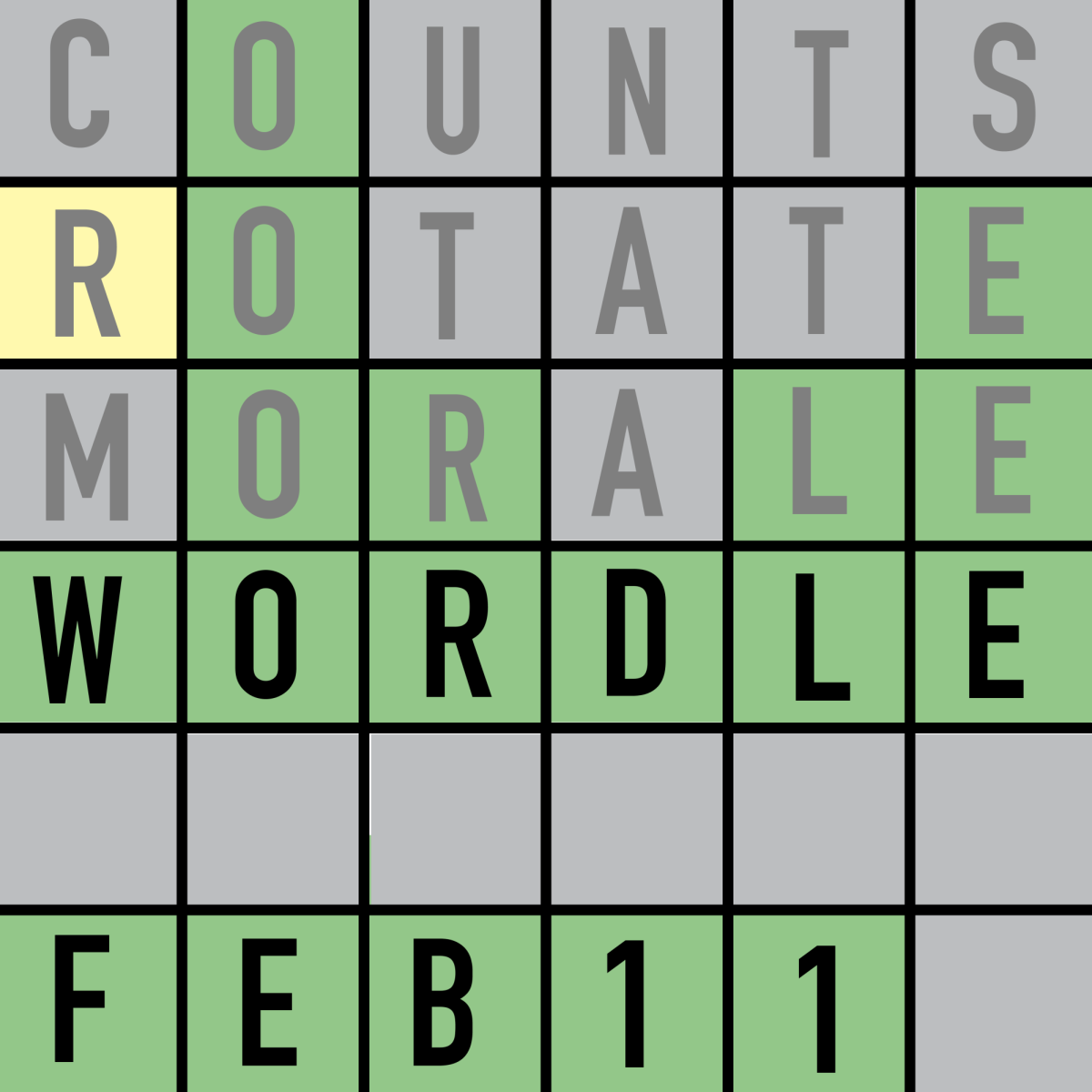

ASSEMBLE THE PIECES: Each member of TechHOUNDS contributes to the building of a robot. The meets every day after school and hopes to earn a $5,000 grant from Ingersoll Rand.

![AI in films like "The Brutalist" is convenient, but shouldn’t take priority [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/catherine-cover-1200x471.jpg)

![Review: “The Immortal Soul Salvage Yard:” A criminally underrated poetry collection [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/71cju6TvqmL._AC_UF10001000_QL80_.jpg)

![Review: "Dog Man" is Unapologetically Chaotic [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dogman-1200x700.jpg)

![Review: "Ne Zha 2": The WeChat family reunion I didn’t know I needed [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/unnamed-4.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)