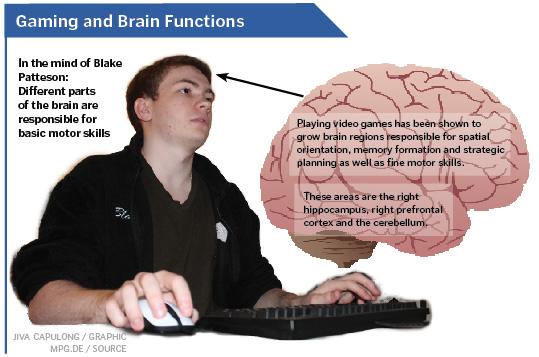

The activity that occupies most of senior Blake Patteson’s time — aside from eating and sleeping — is the video game StarCraft II. It is little wonder that over the years, Patteson has managed to accumulate over 1,000 hours of gaming. This figure, however, doesn’t even include watching online tutorials or matches: Patteson said he has watched at least two or three times as much as he has played. The result of such dedication? He holds the coveted title of “grandmaster,” which indicates his position among the top 200 StarCraft players in the Midwest.

The activity that occupies most of senior Blake Patteson’s time — aside from eating and sleeping — is the video game StarCraft II. It is little wonder that over the years, Patteson has managed to accumulate over 1,000 hours of gaming. This figure, however, doesn’t even include watching online tutorials or matches: Patteson said he has watched at least two or three times as much as he has played. The result of such dedication? He holds the coveted title of “grandmaster,” which indicates his position among the top 200 StarCraft players in the Midwest.

StarCraft II is a real-time strategy game in which players maneuver and command massive armies in order to destroy their opponent’s armies. But the game is about neither violence nor destruction. It’s not even about weapons or shooting, which one would normally encounter in a warlike game. Rather, StarCraft’s essence lies in constant planning and thinking, according to Patteson.

“You have to know what your opponent (is) doing and figure that out and control your own units to best react to it,” he said.

Simply reacting to an opponent’s advance is challenging enough, but a combination of action and reaction creates what Patteson refers to as “chess on steroids.” Because of the intense mental work that is required in StarCraft, the game yields effects that carry beyond the computer screen.

“Before StarCraft, as far as school problems go, I’d always follow exactly what the teacher says, and if that didn’t work, I would get confused and give up. But what StarCraft teaches you is there is no right answer, really,” Patteson said.

His observations are in accordance with recent studies on cognition. According to a 2013 article published in the journal PLOS ONE, playing strategy-based games such as StarCraft is related to enhanced cognitive flexibility, the ability to rapidly adapt and switch between contexts as well as simultaneously think about multiple ideas. As a core component of thinking, cognitive flexibility plays a massive role in solving problems fluidly in the manner that Patteson described. This study could explain Patteson’s newfound speed in perceptual processing.

One of the three authors of the article was Bradley Love, professor of cognitive, perceptual and brain sciences at University College London. According to Love, the decision to use StarCraft in the study hinged upon its emphasis on “monitoring and adapting to changing situations fluidly.” StarCraft was unique in this manner, according to Love, since other games such as The Sims lacked this element. In fact, The Sims served as the control for his experiment.

As a result of StarCraft’s apparent focus on adapting to foreign and rapidly fluctuating circumstances, Patteson said he has adapted a similar manner of fluidly solving problems. He said he considers the end result the most important. “As long as you win, as long as you get the result, it doesn’t matter how you get there. You’ll have people doing crazy stuff that’s like, ‘Why is this working?’ when it works. And maybe that becomes the new standard,” he said.

Luke Obrique, former StarCraft grandmaster and sophomore, put it more succinctly: “When you keep playing strategy games, your mind develops to the point where you’re more reactive to what’s going on in the environment,” he said. In Obrique’s case, he said he had progressed to a point in which he could anticipate an opponent’s strategy rather than simply react to it. “From the beginning of the game, I immediately try to read what the enemy tries to do beforehand, and I react accordingly to it,” he said.

Luke Obrique, former StarCraft grandmaster and sophomore, put it more succinctly: “When you keep playing strategy games, your mind develops to the point where you’re more reactive to what’s going on in the environment,” he said. In Obrique’s case, he said he had progressed to a point in which he could anticipate an opponent’s strategy rather than simply react to it. “From the beginning of the game, I immediately try to read what the enemy tries to do beforehand, and I react accordingly to it,” he said.

Cognitive flexibility also involves the notion of manipulating multiple ideas at the same time. According to Patteson, StarCraft also exhibits this component.

“For StarCraft, multitasking is a huge part of the game, and you’ve got to be able to make units. You start off in one base and six workers. Then you’ll add more and more workers, more and more bases. Once you have workers and bases, you’ll have an army. You’ll have to split the army into multiple places for optimum damage. And so you’ll have three or four army hotkeys, and these allow you to jump to each portion of the army. So you’ll go like, ‘3-3,’” he said, referring to the numbers on the computer’s keyboard. “This is my drop. So you’ll drop. And ‘4-4,’ this’ll be your main army attack. And you’ll be like ‘5,’ send the overlord to go scout and ‘6-6,’ where is my opponent? Is he dropping? I have to figure that out. And ‘1-1,’ I have to keep making units. ‘2-2,’ I have to inject my hatches. So you just have to keep doing all these different things at once.”

What inevitably results from this multitasking is highly convoluted game play, according to Patteson.

As if this was not complex enough, players must also worry about a concept called macro- and micro-management. “Macro is being able to make everything and getting your timing right and getting your build order right on the nail,” he said, explaining that build order was a series of steps that one takes to achieve a specific strategy. “Micro is getting the best out of every unit. If you just macro and have no micro, you’ll never win any game. But if you only micro and no macro, you’ll never win any game. It’s this balance where it has to be very precise.”

Despite Love’s study about the cognitive training StarCraft seems to implement, he said he cautions against jumping to conclusions, due to the relative nascence of research on gaming. “Science is great at figuring out how things work, but it takes time, and it’s never a good idea to make decisions based on one or two studies. Thus, at this point, I don’t think people should play games just because they think they will benefit cognitively,” he said, via email. “If they already like gaming, it’s nice to know that recent studies find benefits. Hopefully, subsequent research converges on the same interpretation, and this study stands the test of time.”

Already though, StarCraft shows great promise as the new chess, clothed in modern colors and looks, according to Patteson. To him, playing StarCraft is satisfying and enjoyable enough. The thrill of overcoming challenging circumstances is even better. But the cognitive flexibility that comes with playing StarCraft is the cherry on top.

![AI in films like "The Brutalist" is convenient, but shouldn’t take priority [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/catherine-cover-1200x471.jpg)

![Review: “The Immortal Soul Salvage Yard:” A criminally underrated poetry collection [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/71cju6TvqmL._AC_UF10001000_QL80_.jpg)

![Review: "Dog Man" is Unapologetically Chaotic [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dogman-1200x700.jpg)

![Review: "Ne Zha 2": The WeChat family reunion I didn’t know I needed [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/unnamed-4.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)