In an ever-changing landscape, advanced statistics are the next big breakthrough in athletics

In an ever-changing landscape, advanced statistics are the next big breakthrough in athletics

Advanced analytical statistics are perhaps the greatest revolution the sports world has seen in the 21st century. With numerous job openings on professional and college athletic teams for statisticians, as well as various new websites like fivethirtyeight.com and kenpom.com, statistics have come out of the shadows and into the athletic limelight.

“At Carmel, some years we have a Ryan Cline ‘15, and other years, we don’t have that. We play a top two or three schedule every year, so every single night we are going against the best in central Indiana and surrounding area, so we are looking for every advantage that we can get,” Tim Estes, CHS men’s basketball team statistician, said. “And we are fortunate to have smart coaches and smart players. We want the stats to tell us how we are doing, to measure ourselves against our team goals. If you’re not managing your performance, you’re not managing.”

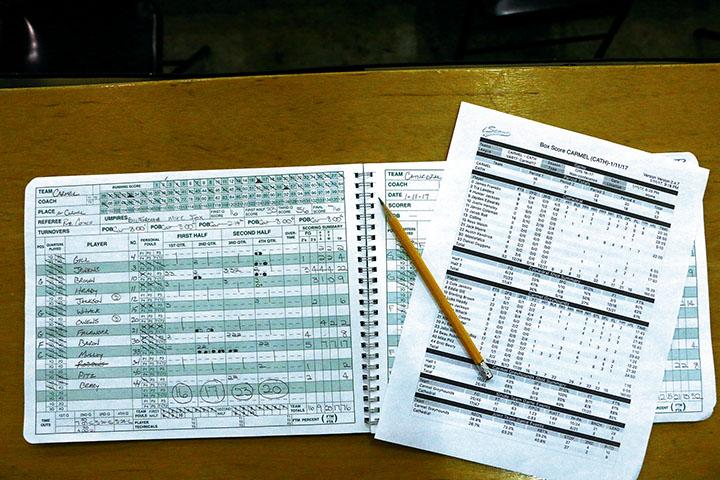

The CHS men’s basketball team is one of many teams—both professional and amateur—who have turned to statistical analysis in order to keep a leg up on the competition. Estes has worked with Head Coach Scott Heady over the course of 18 years at different schools to provide him with statistical analysis. Recent technological improvements, like the iScout app and Hudl app, have allowed for better, more advanced and more consistent statistics – something that the coaching staff has fully embraced.

Estes said, “Where my input comes in is, I do talk with the coaches at halftime and at the end of each quarter, and my input tends to center around, ‘How are we shooting? How are they shooting? Are there any particular players who are on fire? Where are the players getting their shots from? I’ve worked with Heady for 18 years, and he’s given me the freedom to speak up at halftime and say, ‘You’re looking at A, B and C, but look at D and what this stat says and we should be focusing more on that.’”

Although in-game analysis is part of Estes’ job, he said his most important impact arguably comes before the ball is tipped. After rewatching every game on Hudl to make sure the stats are correct, Estes inputs the numbers into a spreadsheet. The numbers are then plugged into a formula created and perfected over the course of many years by Estes himself. While the basic stats like points, rebounds and assists are there, so are other stats that reflect what Estes calls Heady’s “key metrics.” They include statistics such as assist/turnover ratio, dividing rebounds into offensive and defensive, and pass deflections on defense. Each number is weighed and assigned a positive or negative value. Once added together, the formula spits out the “productivity” of a particular player. Estes compiles the productivity rating for each player every six games for the staff.

“I think that the coaches use my reports to really analyze who should get more or less playing time, and of course it’s not the only factor, but it is a significant one, especially as we have statistics per minute, which means that a player could be very efficient, but not getting a lot of time on the court, and maybe they should get more playing time,” Estes said.

The players have full access to these charts as well, with the 20 to 25 “key metrics” being put up on a wall within the locker room and individual leaders’ names being highlighted.

“It’s almost a competition to see who has the highest productivity,” sophomore basketball player John-Michael Mulloy said. “Even though you’re not scoring the most points, having the highest productivity rating means you’re playing the best, so it’s definitely a competitive aspect of the locker room.”

However, with the increasing use of statistics to make decisions in the athletic world, statistics teacher Matt Wernke said he urges caution. Often times, he said, we have a lot of numbers that are good to have, but the way we compare them can be inappropriate, and with a poor comparison of numbers, comes a poor decision. And while he said statistics can be incredibly helpful, especially when trying to predict a future play, we have to be mindful of all the other variables that comprise athletics.

“Of all the things that can affect athletic performance, we can only measure a tiny fraction of it,” Wernke said. “Chemistry, heart, trash talk, all are things that you can’t account for.”

While statistics have become a huge part of the game, many discredit the belief that statisticians are now a necessary part of the game, a classic “new school vs. old school” divide. Both Estes and Mulloy agreed that Heady is an “old school guy,” yet he still approaches the game from a statistical angle because they said he believes it gives him an advantage. For his part, Wernke said he believes a mix of the two is the best approach to the game, regardless of sport.

“We second guess a lot, but the coach is the one talking to the players every day,” Wernke said. “What if his kicker has a tweaked ankle? Maybe that’s why they didn’t kick the field goal. Maybe his defense is gassed and that’s why he went for it on fourth down. No one will ever really know and you can’t ever truly replicate that specific situation again.”

Mulloy said, when he was younger, statistics didn’t matter at all – he got a double-double by accident. But now, Mulloy says he is consciously aware of all the things he can do, whether it’s deflecting passes or grabbing rebounds, to achieve the highest productivity rating possible. While he said he does believe in the cliché, “stats don’t lie,” he also said he understands that no one statistic ever defines you as a player.

“Statistics have always helped me gauge how well I’m playing. I know I play my hardest every game, but sometimes the ball doesn’t go in,” Mulloy said. “Just because you had a statistically bad game doesn’t mean you’re a bad player, and that’s why Coach Heady does it every six games, so he has an average that he can use.”

Wernke echoed the same thought for coaches: They can always make a statistically correct decision, but they will be viewed on the success of the decision. If it works, they are a genius. If it doesn’t, they will go down as an idiot, Wernke said. But statistics are only going to grow in importance as athletic competition becomes more nuanced, more analytical and more multi-dimensional as coaches, players and general managers all seek to gain any extra advantage they can find, something that Estes takes in stride.

“I think (statistics) is a huge part of sports,” Estes said. “I’ll be honest, we lost a regional game last year where we had a three-point lead late in the game where we had to make a decision: should we foul to force two free throws or make them take a tough three-point shot? Well, we decided to play a good defense and he hit (the shot) and we ended up losing in overtime. Was it the wrong decision? I don’t think so, the kid took a shot he misses probably 75 percent of the time. But if he shoots free throws and you multiply the probability of him hitting the first free throw, times missing the second free throw, times the team getting an offensive rebound, times them making the basket and it ends up being only like 11 percent. So if we get into this situation again thisyear, maybe we foul because the statistics show that fouling gives us a better chance to win. That’s the beauty of statistics.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Carmel High School - IN. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

![AI in films like "The Brutalist" is convenient, but shouldn’t take priority [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/catherine-cover-1200x471.jpg)

![Review: “The Immortal Soul Salvage Yard:” A criminally underrated poetry collection [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/71cju6TvqmL._AC_UF10001000_QL80_.jpg)

![Review: "Dog Man" is Unapologetically Chaotic [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dogman-1200x700.jpg)

![Review: "Ne Zha 2": The WeChat family reunion I didn’t know I needed [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/unnamed-4.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)