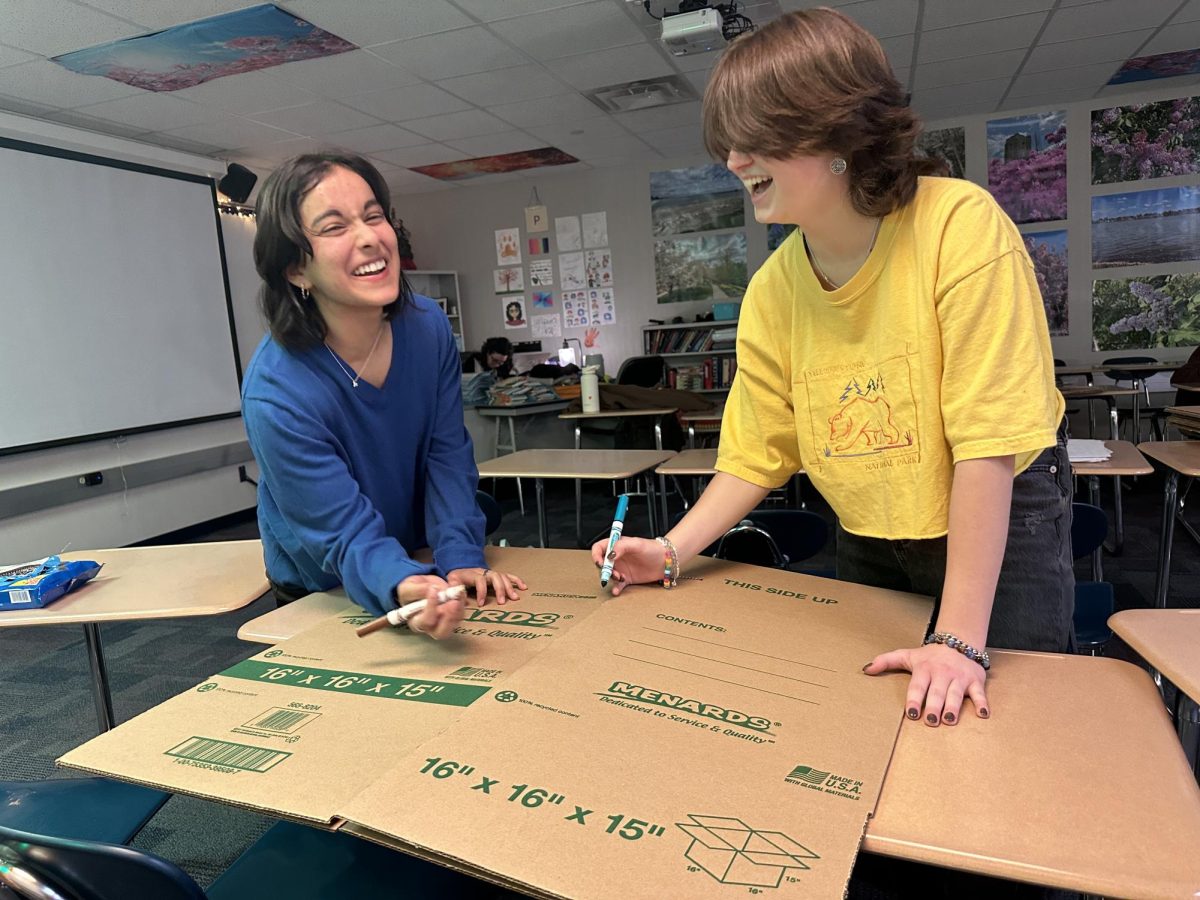

You know how some books, after you finish them, just make you feel this urge to discuss? Like willingly write a literary analysis on it, for fun, because there is so much to unpack? Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card definitely had that effect on me, so here I present unto you: a book review. (Also, I can conveniently fulfill the “rant-filled review” promise we’ve made in our MUSE blurb, which has yet to be delivered.)

Let me start off by saying that Ender’s Game is underhyped, and that is a statement I never thought I’d make. After all, Ender’s Game has been floating around as a classic sci-fi probably ever since it’s been published, so I naturally assumed it was some overrated, possibly slow, novel about white middle-aged men and aliens. Don’t get me wrong, it does have white middle-aged men and aliens, but the main character is actually a six-year-old genius, Ender Wiggin. (A genius kid character is infinitely more interesting than some middle-aged man. No offense to Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy—another one of my favorite sci-fis.) Furthermore, Card’s blunt prose makes the book go by incredibly fast, and the story beats never take a break—there’s always something new, whether it’s a new aspect of the world being introduced, a new character, a new plot development, a new inner dilemma, and so forth. Card even manages to finesse such large amounts of development in a natural manner, despite being so fast-paced. (James Patterson, please take notes as Maximum Ride and Daniel X have given me permanent whiplash.)

The most powerful aspect of Ender’s Game is likely Card’s characterizations, especially of all the kids in the book. Rarely have I read natural or compelling child characters; most times, the younger the character is, the more they can read like simplified cliches. Yet while I wouldn’t call Card’s young characters natural, they are undoubtedly compelling. He perfectly balances the naivete and complexity of a child’s mind while creating such a uniquely devastating character—actually, multiple uniquely devastating characters. I teared up so many times reading this novel (okay, maybe it was mostly because I’m a sucker for blunt prose; it just reads more emotionally, alright?) due to the amount of pain Card puts all the children through. Ender, in particular, is deliberately written as an extremely lonely and isolated character, and not even through his own actions. The lack of choice is perhaps what made me feel a bittersweet, hopeless triumph about Ender’s journey: He is able to push past one obstacle after another, and yet never has full awareness nor autonomy throughout the entire book, instead living his life constantly as others have shaped it.

Furthermore, Card essentially provides his own character analyses, as the book is an extremely psychological read and fraught with internal dilemmas. Consequently, when reading Ender’s Game, I found it important for me, at least, to recognize that, similar to how “book science” is often dramatized rather than accurate, psychology is much the same. Card is certainly skillful at writing psychological tension and sweeping aphorisms; just after finishing the novel, I was firmly convinced that Ender’s Game should replace Art of War as recommended reading for military personnel. After a few days, though, I realized that Card doesn’t have a psychology or military degree, nor does he have any specialized experience with such topics. Rather, he was writing a fictional novel. That put the book into a clearer perspective for me as a reader, although I definitely still enjoyed the highly psychological aspects.

However, that’s not to say I don’t have any criticisms of the book itself. As I’ve just touched on, Card’s immersive writing paints a (seemingly) realistic picture of human psychology—but he does so with a grim, Machiavellian brush. Hence, it’s pretty easy to be left in a weird headspace while and after reading the book; I certainly felt pessimistic for a few days. (That’s, admittedly, also the mark of a good book, but I just wouldn’t recommend Ender’s Game if you’re looking for some cozy, feel-good escapism.)

A more crucial criticism I have rests with Card’s ideological viewpoints and how they peek through, albeit very rarely, in the novel. He was known for being homophobic; Ender’s Game also hints at sexist undertones. While I don’t think an author’s ideology detracts from their writing itself (as Walt Whitman put it, people contain multitudes), it is something to bear in mind. At the same time, it’s relevant to note that this book was published decades ago, so there’s certainly some author-reader disconnect (for instance, there’s significant emphasis on America vs. Russia, a solid indication the book was written during the Cold War era).

Overall, I think Ender’s Game is an excellent novel for contemplation while you read, and an even better novel for scrutiny after you finish.

On this blog, Shruthi Ravichandran and Grace Xu provide monthly curations of all types of arts and media, from TV shows to music to novels to even YouTubers. On top of mood-oriented playlists, there’s also the occasional rant-filled review. They hope readers will always leave with a new piece of media to muse over. Click here to read more from MUSE.

![AI in films like "The Brutalist" is convenient, but shouldn’t take priority [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/catherine-cover-1200x471.jpg)

![Review: “The Immortal Soul Salvage Yard:” A criminally underrated poetry collection [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/71cju6TvqmL._AC_UF10001000_QL80_.jpg)

![Review: "Dog Man" is Unapologetically Chaotic [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dogman-1200x700.jpg)

![Review: "Ne Zha 2": The WeChat family reunion I didn’t know I needed [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/unnamed-4.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)

![Book Review: Ender's Game (Spoiler Free) [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/413CF4DD-9B7C-4D64-97ED-70A297DD4E1D-900x528.png)