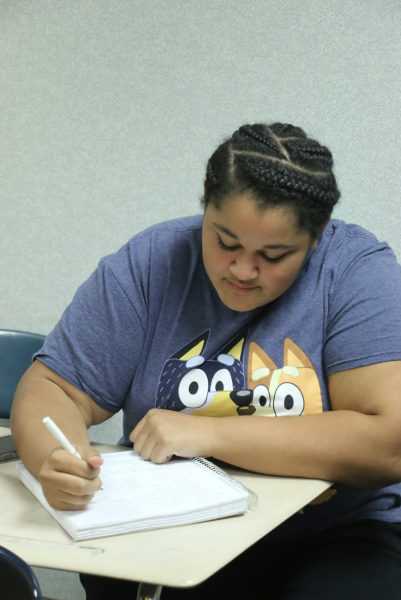

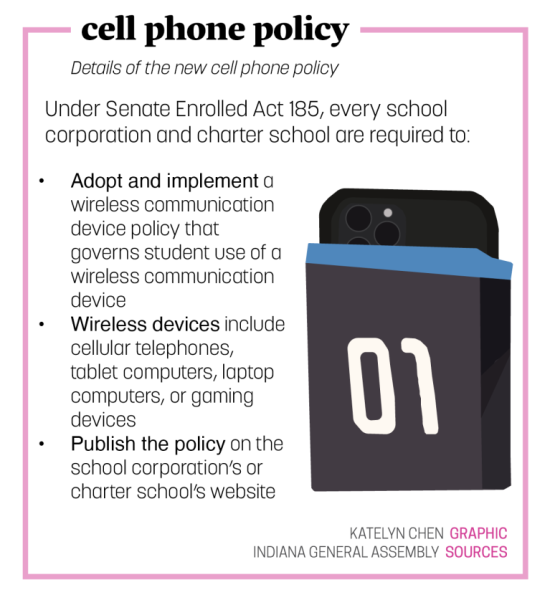

On average, students pick up their cell phones 51 times during the school day, according to Common Sense Media. After noticing reduced academic engagement due to screen time, this year Indiana legislators signed a law that required a policy to restrict student phone usage during instructional time. After two months of implementation, junior Gaia Shields said she has grown to appreciate the change.

“At first, the cell phone policy was really inconvenient for me,” Shields said. “It seemed annoying because I’d always have to put it away and I wasn’t able to check my messages. When I take my phone out at the end of the day, it’s fully charged, which is new. I’ve noticed I’m much more productive.”

Like Shields, sophomore Sid Sinha said he originally disliked the cell phone policy, but that it has helped him with his academic performance.

“The cell phone policy positively impacted my day-to-day life at school,” Sinha said. “During school, I’ve been more efficient with my work since I’ve not been distracted by my phone. As a result, my grades have improved and I am more aware about what’s been happening in my classes.”

Increased engagement

Shields said the policy has made productivity simpler, with fewer people being inclined to use their cell phones during class.

“I think academic performance is going to improve, especially because SSRT is included in the phone policy,” Shields said. “Before, a lot of people were constantly on their phones in SSRT. Personally, I’ve already seen improvement in my productivity. I think a lot more people are putting more attention to their schoolwork during this time.”

Similarly, math teacher Laura Diamente said her students are responding well to the new policy.

“I have to occasionally remind people to put their phones away, but it’s 95% better,” Diamente said. “As for the benefits, people are more focused and paying attention.”

Like Diamente, English teacher Chad Andrews said the policy has gradually improved students’ attention.

“The first few weeks, the change that resulted from the policy was hard to notice,” Andrews said. “Now, it’s clear students are more engaged and present in class. Students now have no option but to be engaged, it’s out of necessity.”

Sinha said the policy increased the level of engagement between peers as well.

“Because of the policy, I talk more with people I don’t know very well,” Sinha said. “In subjects where I don’t know many of my classmates, like Spanish, I talk with the people around me for assignments, which is something I did not do often before the policy.”

Like Sinha, Diamente said she’s noticed improved social interactions due to less phone and social media usage.

“The amount of engagement that my students have with one another now is tenfold compared to what it used to be,” Diamente said. “I mean, you know, if I gave a five minute break, it was silent, and everybody was just on their phones. Now, everybody’s talking with one another. They’re learning about the people around them more, and there’s definitely more interaction. And I think that’s what humans, on average, need, is interaction with one another.”

Along with stronger engagement, Shields said her attention span and focus have also sharpened.

“I never noticed how I’d subconsciously pick up my phone when I got bored or didn’t want to do something,” Shields said. “Keeping your attention on one thing is a good habit to form. It’s great for high schoolers to prepare and practice for the workplace.”

Although phones and technology are prevalent in society, Andrews said he urges caution as they often pose as distractions.

“Technology is a significant part of the world, therefore distractions will also arise,” Andrews said. “There’s something to be said for brain and social development, all of which are happening at these younger ages. There’s a reason, for example, why there are privileges that adults have that young kids don’t. Teenagers’ brains aren’t fully developed and will react much stronger and differently to phones than an adult.”

Impact on the classroom

While some said they are weary of phone usage in the classroom, Shields said it’s important to consider students who are effective digital learners.

“This policy has definitely impacted students who are more inclined to use technology to learn,” Shields said. “However, this may not have a negative impact.”

Without freedom of devices, Sinha said there has been a small shift in the overall environment of classes.

“The atmosphere of most of my classes didn’t change much,” Sinha said. “However, in a few of my classmates, the teachers started paying more attention to more rules in general, making the entire class stricter. I think this policy could pave the way for more restrictions on the students. In the future, we might start having less freedom in extra time like SSRT, lunch or passing periods.”

But while some see restrictions, Andrews said the policy transforms students’ learning environment for the better.

“With the cell phone policy, there is room for debate about the negatives and where we can have those exceptions,” Andrews said. “Overall, school isn’t just about what we learn, but how we learn. Students should learn in the process of school how to regulate themselves, how to pay attention and socialize. All of those things can be compromised when focusing on technology.”

Similarly, Shields said the benefits of the policy are widespread.

“The positives outweigh the negatives with the phone policy,” Shields said. “It helps people branch out, creates longer attention spans and improves productivity.”

As technology in society continues to evolve, Andrews said the policy should evolve alongside.

“The policy should continue adapting as limits or weaknesses arise,” Andrews said. “It will become apparent to us where we need to improve and where we can make exceptions. The policy should aspire to be better, while acknowledging the realities.”

![AI in films like "The Brutalist" is convenient, but shouldn’t take priority [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/catherine-cover-1200x471.jpg)

![Review: “The Immortal Soul Salvage Yard:” A criminally underrated poetry collection [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/71cju6TvqmL._AC_UF10001000_QL80_.jpg)

![Review: "Dog Man" is Unapologetically Chaotic [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dogman-1200x700.jpg)

![Review: "Ne Zha 2": The WeChat family reunion I didn’t know I needed [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/unnamed-4.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)