Sophomore Jose Tadeo Yanez said he feels judged when he uses an English dictionary during the PSAT. Yanez is from Venezuela and primarily speaks Spanish, which makes him one of many English as a First Language (ENL) students here. These students are allowed various accommodations for things like the PSAT, but that can come with its own problems. He and his friends have faced racism from both teachers and classmates.

“Teachers outside of ENL keep accusing me and my friends of skipping class frequently without any proof. My classmates in elective classes often laugh at my accent when I am simply trying to improve it through fluent conversation,” Yanez said. “ENL has helped me gain a lot of confidence in speaking English, but only with my friends.”

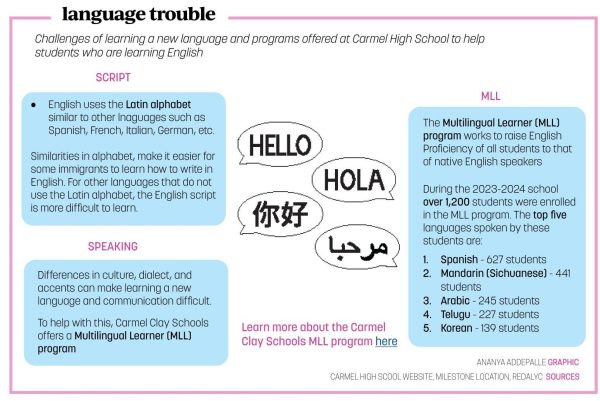

Yanez is not alone in facing these challenges. According to the Indiana Department of Education, over 129,000 students speak a language other than English, including more than 77,000 classified as English Language Learners (ELL). Since 2015, the number of multilingual learners in Carmel Clay Schools has grown by 111%. At CHS, there are over 1,267 multilingual learners, comprising 23% of the student body.

ENL teacher Gabriela Mendoza said her students are working hard to speak in English, but some native-speaking students, she said, can delay that progress.

“I keep receiving complaints from my students about feeling left out due to the attitudes they receive from native students,” Mendoza said. “This makes my job 10 times harder because I not only need to provide this group of kids with the necessary skills to succeed in English, but I also have to address the confidence issues that are making all of my work pointless.”

Mendoza said she is dedicated to her students’ success and wants to help them realize their potential. She believes every student possesses unique skills that deserve recognition. Through hard work, she hopes her students will become more confident and proud of their achievements.

“The way my students solve math problems or tackle science homework is identical to how native students do it, but the main issue is that they struggle to explain how they arrived at their answers in English,” Mendoza said.

Many ENL and ELL students in Indiana face discrimination. According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), about 20% of immigrant students have reported being bullied or treated unfairly because of their background. This can lead to feelings of isolation and stress, impacting their academic performance and overall happiness. Teachers and staff may not recognize these issues, and according to the U.S. Department of Education, it makes it more difficult for immigrant students to seek help.

Yanez said he and his friends dislike attending football games and prefer to remain by themselves due to a past experience that altered his feelings about such events.

“My friends and I were really excited to watch the first football game of our sophomore year, but it turned into a nightmare. A group of about seven kids kept calling my friends and me ‘Mexicans’ and saying we didn’t belong here,” Yanez said. “It was a long night that almost escalated into a fight, but thank God I was able to prevent my friend from retaliating.”

As more non-native speakers arrive at this school, those types of problems may become more common.

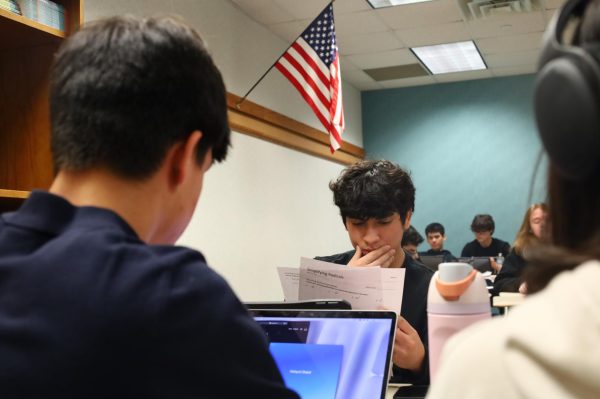

“Teachers keep accusing me and my friends of skipping class without any evidence, and it’s really hard to defend myself since I am still learning English,” freshman Alberto De La Rosa said. “Teachers in my math and biology classes treat me as if I have a special condition when all I want is to learn like everyone else.”

De La Rosa said he finds the scrutiny from teachers and peers “annoying.”

“I understand that I look different and that my pronunciation differs from what people are used to,” De La Rosa said. “But it becomes really frustrating when people just stare at you, your clothes, or the way I act in class as if I were some kind of wild animal.”

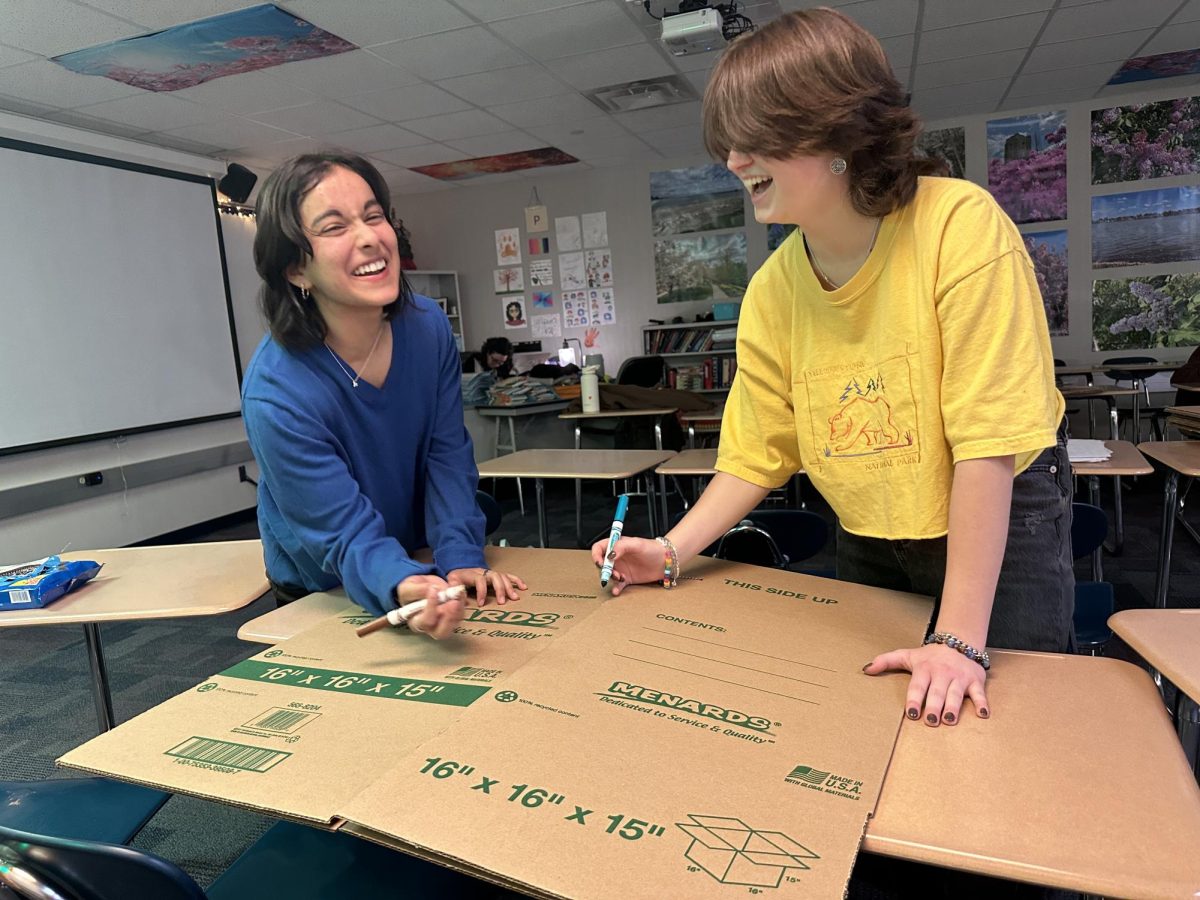

To combat these issues, Mendoza said she began advocating for her students, encouraging staff to foster a more welcoming environment. For example, she has offered workshops to educate staff and students about cultural sensitivity. She has also paired native students to mentor ELL students. She said these initiatives began to cultivate a supportive atmosphere within the school.

“To help my students, I started encouraging everyone to create a friendlier school. I held workshops to teach about different cultures and paired native students with those learning English. This made our school a more supportive place,” Mendoza said.

Yanez said he appreciates their efforts.

“Despite the obstacles I’ve faced, Mrs. Mendoza made me realize that I can transform my experiences into strength,” Yanez said. “If I can gain confidence, I can begin sharing my stories, showing classmates and teachers that being different is a gift, not a flaw.”

![AI in films like "The Brutalist" is convenient, but shouldn’t take priority [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/catherine-cover-1200x471.jpg)

![Review: “The Immortal Soul Salvage Yard:” A criminally underrated poetry collection [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/71cju6TvqmL._AC_UF10001000_QL80_.jpg)

![Review: "Dog Man" is Unapologetically Chaotic [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dogman-1200x700.jpg)

![Review: "Ne Zha 2": The WeChat family reunion I didn’t know I needed [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/unnamed-4.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)