It’s lunchtime. Hundreds of students go through cafeteria lines, picking up entrées such as spaghetti and meatballs, chicken parmesan or pizza. Still others unpack their own lunches. Junior Marisa Arakawa takes a sandwich out of her lunch box. Some students get white skim milk to be healthy while others choose to hold off on dessert. As far as healthiness is concerned, does anyone keep sodium in mind?

Arakawa is among the many students who are aware of their diet. She said she considers herself knowledgeable about the food she eats, yet admitted to only “kind of” knowing about the problems of high sodium consumption. An American Heart Association article published Oct. 21, 2013 recommended people to “aim to eat less than 1,500 mg of sodium per day.” However, the article cited that Americans, on average, consume 3,436 mg of sodium per day —an amount well over twice as much as is recommended.

students who are aware of their diet. She said she considers herself knowledgeable about the food she eats, yet admitted to only “kind of” knowing about the problems of high sodium consumption. An American Heart Association article published Oct. 21, 2013 recommended people to “aim to eat less than 1,500 mg of sodium per day.” However, the article cited that Americans, on average, consume 3,436 mg of sodium per day —an amount well over twice as much as is recommended.

As a vegetarian, Arakawa said she considers herself aware of the food she eats.

“I think (I am aware) maybe more so than other people because my mom is conscious of it,” Arakawa said. “It reflects our family diet.”

Arakawa and her entire family are all vegetarians. She said she has been a vegetarian since she was three or four years old, when her parents decided to make the switch to a vegetarian diet. She said this has led her to eat healthier.

According to Brooke Pearson, independent consultant at Butler University and registered dietitian, a vegetarian diet usually contains less sodium as opposed to a diet including meat. Pearson said that processed foods such as lunch meats contain high amounts of sodium. Because vegetarians do not have the typical “ham and cheese” sandwich in their diet and tend to have more fresh vegetables and fruits, foods that are naturally very low in sodium, vegetarians generally intake less sodium per day.

Pearson said most sodium is consumed from processed foods, ranging from pizza and breads to soups and sauces. Yeast breads contribute high amounts of sodium to diets not because of their high sodium per serving, but because people eat so many servings of bread a day.

Additionally, Pearson said that because Americans tend to consume too many calories per day, this naturally increases their daily intake of sodium.

Richard Mattes, professor of foods and nutrition at Purdue, said via email, “The primary source of sodium in the diet is processed foods, dairy products and baked goods. The former are high in sodium. The latter two are not necessarily high, but we consume this in high quantity, so they contribute a good deal of sodium. The salt shaker is actually a small contributor, as are salty snacks.”

Pearson’s first suggestion to keeping sodium consumption under control is reading food labels.

Upon reading, she said people should choose the food lower in sodium or choose the sodium-free option. She said people need to find out where the sodium comes from in their diets and reduce their consumption of those foods.

In the same way, Arakawa said people should read food labels to get knowledge about what the food contains.

Additionally, in order to control amounts of sodium, Pearson stressed the importance of eating a diet with more fresh fruits and vegetables, which contain very low amounts of sodium.

Additionally, in order to control amounts of sodium, Pearson stressed the importance of eating a diet with more fresh fruits and vegetables, which contain very low amounts of sodium.

Mattes said that long-term effects from overconsumption of sodium depend on the individual.

“Some individuals can consume high amounts with no apparent adverse effect. For some people, their blood pressure is responsive to sodium intake,” he said. “There is a genetic basis for reactivity to dietary sodium. Unfortunately, we don’t know how to test for this now.”

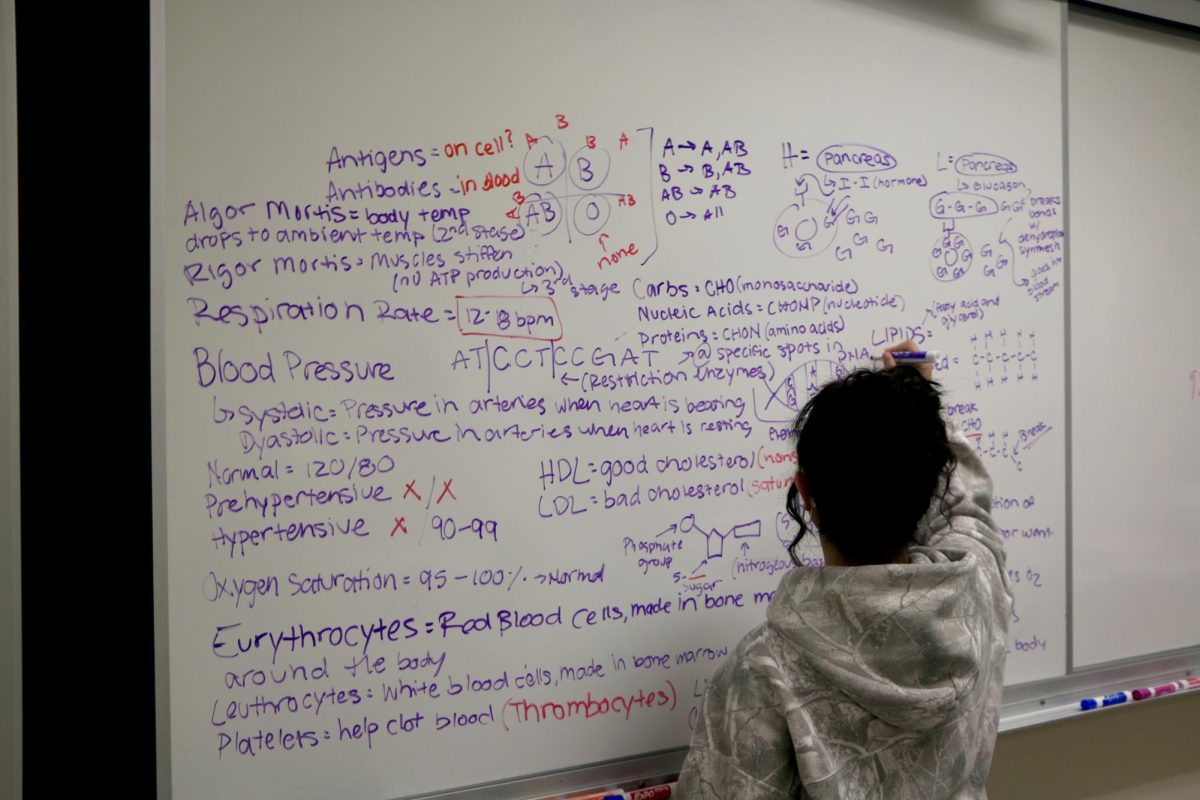

Similarly, Pearson said the biggest adverse effect from too much sodium is hypertension. She said increased blood pressure is hard on the kidneys and heart, which makes people more susceptible to heart disease, including heart attacks.

Holly Huepenbecker-Hull, assistant cafeteria manager for the main cafeteria, said, “I don’t think students are aware of sodium (intake).”

Yet, the food service staff has taken measures to control amounts of sodium.

She gave an example of a can of green beans. She said the cafeteria gets the green beans with no salt added, but just to make sure, they rinse them as well. She said they are not allowed to add salt, but instead they add seasoning, another suggestion given by Pearson to reduce sodium consumption.

Huepenbecker-Hull said the Competitive Foods Act, which will be officially enacted for the 2014-15 school year, affects the amount of sodium in foods. While the first target does not begin until July 1, 2014, she said that the staff is trying to get ahead of the ball game by having foods that already meet this act’s standards this year. Standards include having school lunches average 1,420 mg of sodium or less. By July 1, 2017, this number drops to 1,080 mg.

Of these changes, Huepenbecker-Hull said, “Manufacturers have to come up with products to meet the guidelines.”

Because of this, she said that decreasing amounts of sodium offered in school meals is something that will happen gradually.

Mattes and Huepenbecker-Hull said they both think awareness of high amounts of sodium is increasing.

Mattes said, “I think most people have heard this, but not knowing what a high level of consumption is or where most of the sodium comes from in the diet, does little to reduce intake. Concern about decreasing the palatability of food also mitigates against reduction of salt in the diet.”

For her part, Huepenbecker-Hull said she has had kids ask for salt at lunch, but there are no salt shakers in an effort to reduce sodium. This, she said, may open their eyes.

Arakawa said further education about food would help.

“People need to be more educated in schools and really just need to learn problems (ingredients in) food can cause,” Arakawa said. “There is a need to teach people that.”

![AI in films like "The Brutalist" is convenient, but shouldn’t take priority [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/catherine-cover-1200x471.jpg)

![Review: “The Immortal Soul Salvage Yard:” A criminally underrated poetry collection [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/71cju6TvqmL._AC_UF10001000_QL80_.jpg)

![Review: "Dog Man" is Unapologetically Chaotic [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dogman-1200x700.jpg)

![Review: "Ne Zha 2": The WeChat family reunion I didn’t know I needed [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/unnamed-4.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)