As the school day progresses, senior Terry Zhou is reminded of the differences in education between China and the United States. These differences go unnoticed by most CHS students, who have never experienced an international education. However, according to Zhou, there is much that CHS and other American schools can learn from schools abroad.

Zhou went to school in China from first through eighth grade before moving to the United States for his high school education.

“Chinese and American education have different benefits and harms to students,” Zhou said.

Despite the benefits of American education, the United States continues to lag behind education abroad due to what Zhou calls the “harms.” The Pew Research Center, an organization dedicated to providing facts and statistics about current issues, published an article in February 2015 concerning the United States’ education compared to foreign education. The article stated in the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) test, U.S. students placed 35th out of 65 countries and economies in math and 27th in science. By comparison, Japan placed sixth in math and third in science. Shanghai, China, despite just being a city, placed first in math and first in science. Even in reading, Japan and Shanghai placed above the United States. The report implies that American students generally have decreased academic literacy compared to several other countries.

French teacher Andrea Yocum, who formerly taught in Senegal through the Fulbright Teacher Exchange Program, noticed several differences between French and American education that may be contributing to the difference. Due to Senegal being a former French colony, its schools are all taught in accordance with the traditional French system.

This French system also performed significantly better than the United States on the PISA exam, placing 24th in mathematics and 25th in science.

One potential reason for the gap between French and American scores may be a more relaxed testing policy in France. This is apparent in the French education system’s quantity of testing.

“(In the French system) you basically have three graded assignments, maximum of four, (per) semester in order to get your credit,” Yocum said. “You have that, and a final exam at the end of the semester.”

Yocum said she found due to having to spend less time on testing, teachers were able to spend more time teaching and ensuring that students understand the material.

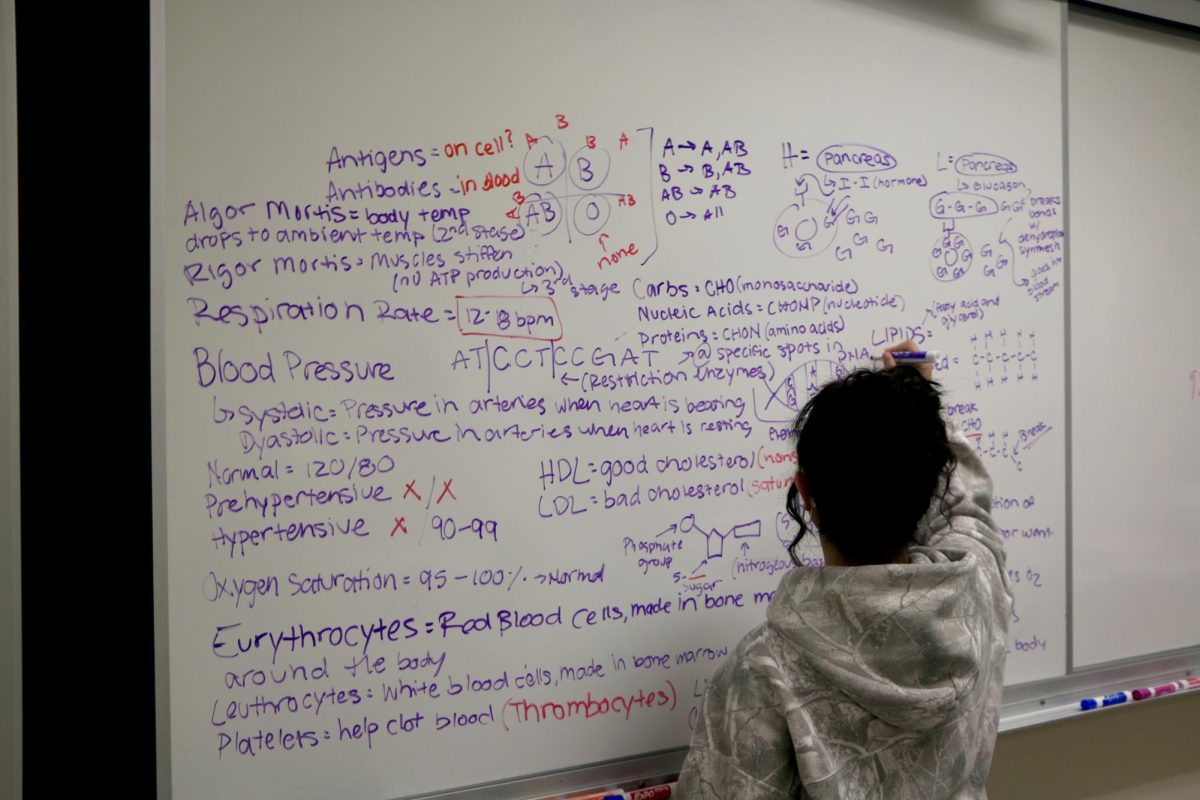

Sophomore Sota Shishikura, who moved to the United States when he was 10 years old, said in Japan, students only had eight tests a semester. He said due to fewer days being spent on testing, students were able to achieve a more rigorous education, especially in math and science. In addition, Shishikura said both math and science classes covered more specific and advanced topics at a younger age.

Sophomore Sota Shishikura, who moved to the United States when he was 10 years old, said in Japan, students only had eight tests a semester. He said due to fewer days being spent on testing, students were able to achieve a more rigorous education, especially in math and science. In addition, Shishikura said both math and science classes covered more specific and advanced topics at a younger age.

Shishikura said, “I learned factoring and the quadratic formula when I was in fifth grade.”

By contrast, in the United States, the quadratic formula is taught in Algebra I, which is taken in ninth grade by the average American student.

Furthermore, Zhou said in China, education focused more on the mastery of basic skills. He said he found this as a sharp contrast to education in the United States.

He said, “Here (in the United States), we focus more on moving on. As soon as you touch base on one skill we move on.”

For example, Zhou said math teachers in China spent a lot of time developing skills such as number sense, while these topics are generally glossed over in the United States.

Zhou said he found this increase in rigor made the Chinese school system more efficient.

Zhou said, “The education in China focuses more on the depth, so you don’t have to go back to a certain topic every single year like we do here.”

This allows students to begin learning new material from the first day of each school year instead of spending months on review. However, rigor in these countries’ education systems is not just limited to subjects such as math and science. This rigor is based on the material being more difficult and in depth. This increased difficulty is reflected in the grading scale.

“(The students under the French system) are graded on a scale between a zero and a 20,” Yocum said, “so a 20 is an A plus, plus, plus, ad infinitum. And what they say in the French system is no one, not even God, receives a 20.”

“(The students under the French system) are graded on a scale between a zero and a 20,” Yocum said, “so a 20 is an A plus, plus, plus, ad infinitum. And what they say in the French system is no one, not even God, receives a 20.”

However, students are not punished grade-wise because they are learning extremely challenging material.

Yocum said, “Here we think, ‘I want to try and get a “C”,’ which is for (French students) a 10 out of 20. For us, this is a 50 percent, but for them, a grade they’re fine with.”

Yocum said, “Here we think, ‘I want to try and get a “C”,’ which is for (French students) a 10 out of 20. For us, this is a 50 percent, but for them, a grade they’re fine with.”

Unique grading scales such as these help ensure that students in these countries are not punished for learning more difficult information.

This different scale is a reflection of the extremely difficult standardized tests students in these countries often take when they are older. While the SAT is a major test for CHS students, standardized tests in top-performing nations hold far greater importance than the SAT.

For example, in China, the Gaokao or National Higher Education Entrance Examination, is taken by high school seniors. Unlike the SAT, students are only allowed one attempt per year on it.

Zhou said, “The result of the Gaokao pretty much determines what college you go to.”

Standardized testing also holds great importance in French educational systems. Students in these countries take the Baccalaureate test. This test takes an entire eight hours and has various forms depending on what the student plans to study in college.

“The Baccalaureate test determines whether or not they’re eligible to go to university,” Yocum said. “If you don’t pass your Baccalaureate, you can’t attend university.”

Students often greatly dislike these tests because of the immense pressure brought with them. Colossal standardized testing is just one way that several people believe these “top”countries go wrong; however, it is also potentially one of the reasons that such countries excel to begin with.

These difficult standardized testing exams often require large amounts of preparation and are very stressful for foreign students.

“Japanese students study a lot,” Shishikura said. “I have a friend in Japan who studies more than seven hours each day.”

Another nuance of foreign education is the strained student-teacher relationship.

“The teachers in a French school system do not have any type of personal connection with the students,” Yocum said. “They basically are like robots that come into the room and present the information.”

“So after about a week of learning their names and, you know, figuring out who they were, they were absolutely shocked. They were like, ‘Oh my goodness,’ and they called me, ‘Miss, Miss Yocum, miss, you know my name!’” Yocum said. “And I was like, ‘Of course I know your name, you’re my student. I’m going to learn everyone’s name.’ And, they would say to me, ‘No other teacher knows my name.’”

“So after about a week of learning their names and, you know, figuring out who they were, they were absolutely shocked. They were like, ‘Oh my goodness,’ and they called me, ‘Miss, Miss Yocum, miss, you know my name!’” Yocum said. “And I was like, ‘Of course I know your name, you’re my student. I’m going to learn everyone’s name.’ And, they would say to me, ‘No other teacher knows my name.’”

In China, better performing students often have a closer relationship with teachers, making high academic performance a desirable goal. Zhou said, “Overall, the student-teacher relationship is significantly affected by the student’s academic performance.”

In addition to the lack of personal connection, there are also strict rules on when questions may be asked in these countries.

Yocum said, “If you were in the middle of a lesson and you’re totally confused, if you raise your hand and ask a question to the teacher, the teacher is just going to be appalled at the impoliteness of that situation.”

Yocum said, “If you were in the middle of a lesson and you’re totally confused, if you raise your hand and ask a question to the teacher, the teacher is just going to be appalled at the impoliteness of that situation.”

The situation is similar in China. Zhou said, “In China the lecture goes on and you ask questions after. Unlike in here where you interrupt them.”

In addition to the varying teacher-student relationships, international views about homework strongly differ from domestic views.

“In the French system, they don’t care if you do your homework,” Yocum said.

She also said homework in France and countries with French schooling systems is not collected and is never taken for a grade. However, she said, oftentimes students do the homework anyways to gain a better understanding of the material.

The amount and difficulty of homework given also differs greatly between countries. Shishikura said, “We have less homework in Japan, but it is more difficult.”

The amount and difficulty of homework given also differs greatly between countries. Shishikura said, “We have less homework in Japan, but it is more difficult.”

Top schooling systems often have more relaxed homework policies than schools in the United States. This increased presence of autonomy may be one reason for these countries’ higher scores.

According to Zhou, international education systems of nations such as China have both benefits and drawbacks. Despite the higher scores on international examinations, he said these scores come at a price.

Zhou said, “(In China) you don’t take electives at all. There are certain subjects you have to take, and everybody takes the same thing. That’s why you don’t take the fun classes like drawing—you don’t take ceramics, you don’t take organic chemistry. You just do the same exact stuff, that’s why they’re ahead.”

![AI in films like "The Brutalist" is convenient, but shouldn’t take priority [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/catherine-cover-1200x471.jpg)

![Review: “The Immortal Soul Salvage Yard:” A criminally underrated poetry collection [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/71cju6TvqmL._AC_UF10001000_QL80_.jpg)

![Review: "Dog Man" is Unapologetically Chaotic [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dogman-1200x700.jpg)

![Review: "Ne Zha 2": The WeChat family reunion I didn’t know I needed [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/unnamed-4.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)