By: Grace Baranowski <[email protected]>

By: Grace Baranowski <[email protected]>

A boy sits in his front-row desk, three from the left in his first-semester class. He yawns, as does another sitting in the back.

The teacher continues to lecture about trusts in turn-of-the-century America. The boy, meanwhile, flips through his textbook and blurts out “Taft” in response to a rapid question.

He’s right.

But something sets this boy apart from the other students. For one, unlike his classmates, he wears his student identification card on a blue lanyard around his neck. And two, senior Caleb deBoer, this boy sitting in William Ellery’s U.S. History class, is a Life Skills student.

The Program

It’s an identification that belongs to 33 other students here. According to Karen Gallagher, special services department chairperson, each student from this group has an individual education program. Rewritten annually, it involves a yearly meeting with the student, his or her parents, the student’s special services teacher, the student’s general education teacher and an administrator. These meetings center on educating each Life Skills student in the “Least Restrictive Environment,” or LRE. According to the Indiana State Board of Education, this means that, “to the maximum extent appropriate, students with disabilities are educated with nondisabled students.” Caleb’s individual program, then, includes his participation in Ellery’s history class.

This goal, “inclusion,” is a little over 30 years old, and it has come a long way since its inception. Congress passed the Education for All Handicapped Children Act in 1975, which started the movement toward inclusion. It then stated that all states had to provide a “free, appropriate, public education” to children with physical, mental or emotional disabilities. In 1997, Congress renamed it the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). It required school officials to justify why a “disabled child” would not participate with his general education peers in any activity, according to CQ Researcher.

Continual change

But the push to include students with disabilities has taken some time. The road to including all disabled children was a “slow process,” according to Tracie Smoot, a special education teacher who works with Life Skills students. At first, administrators only moved “low-risk students” out of “segregated” buildings. “Then,” she said, “when they saw that that was successful, they moved students with more significant disabilities.” Earlier, students were either in the general or special education building. Now, the success rate is higher. “There are a lot more options,” Smoot said. “We’ve come a long way since I started (16 years ago). When I started, I worked with maybe seven general education teachers. Now, we’ve expanded into all of the departments.”

And even 10 years after the overhaul, changes are still being made.

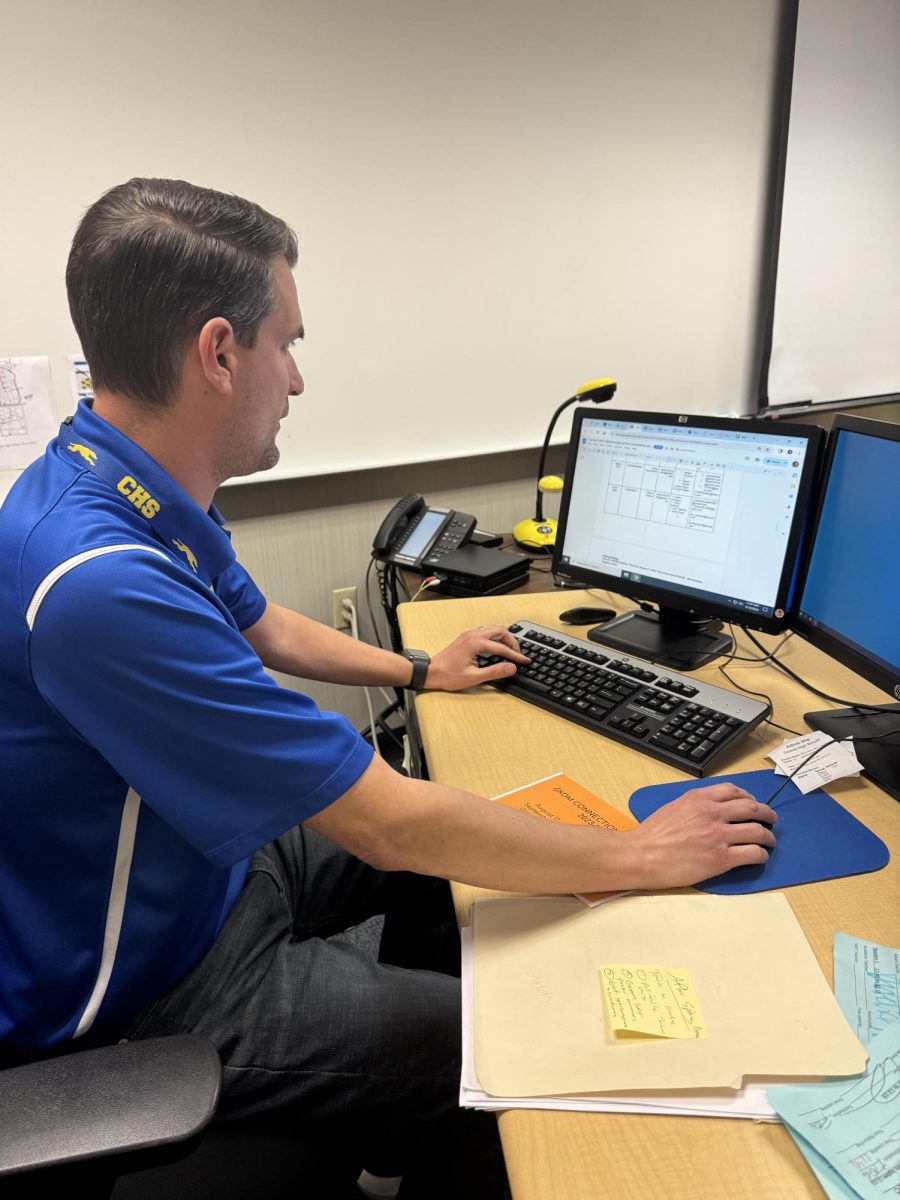

According to Gallagher, “We are constantly striving to improve our program for students. Each year we identify needs and set new goals to continue to seek the best educational programming for students. This year, we are focusing on curriculum development. Last year, Carmel Clay Schools conducted a program review of our Life Skills program.” An increase in technology usage is also a goal for the future, she said, as life becomes increasingly modern.

But while Gallagher’s outlook on the Life Skills program focuses on the positive, Lisa Pufpaff, PhD, assistant professor of the department of special education at Ball State University, said that she doesn’t foresee much change in the next few decades. “Public education has far more pressing hurdles (e.g., standardized test scores) than inclusion, and until there is a public outcry for change, little will be done,” she said via e-mail. Pufpaff also pointed to the difficulty of inclusion, as “much of the academic curriculum is beyond the capabilities of those with moderate-severe cognitive impairment. On the other hand, the social interaction and intellectual stimulation of the general education curriculum is very appropriate for some students.”

Delicate Balance

Consequently, a very fine line exists within this goal of inclusion—and necessarily so, because the degree of inclusion is calibrated to each student’s optimal success.

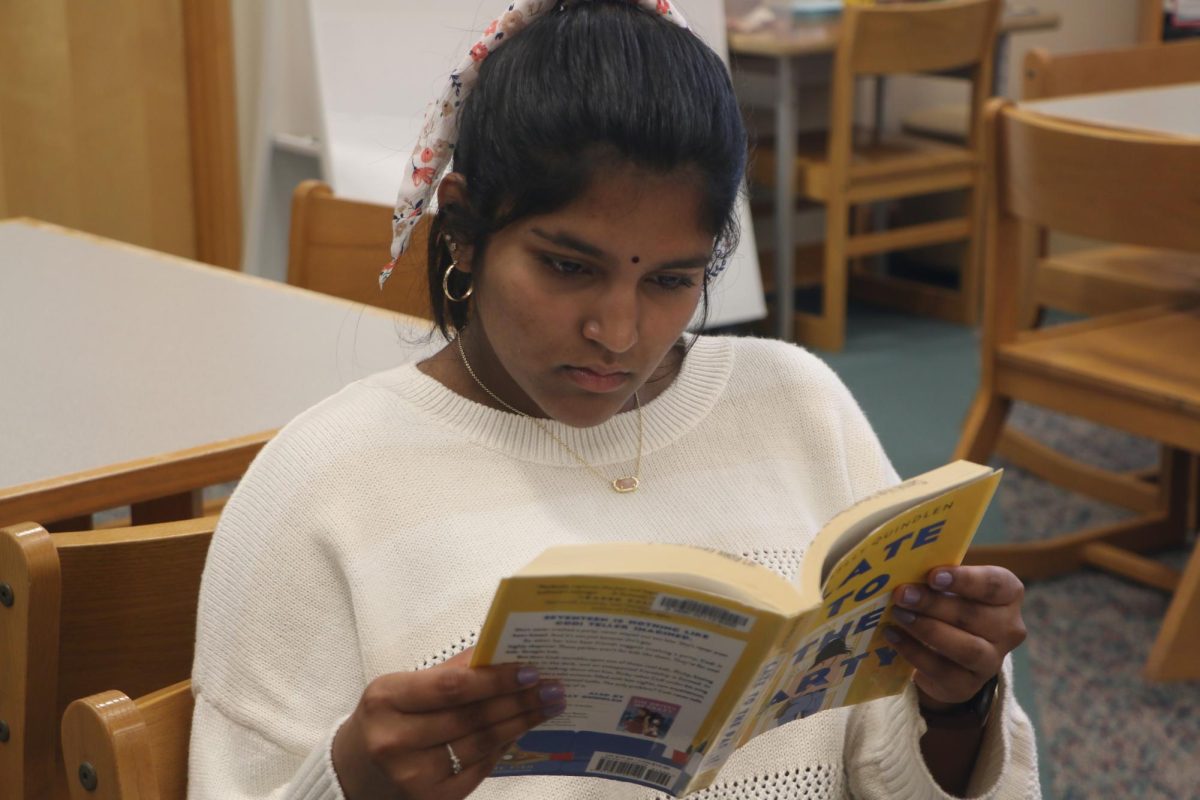

According to Smoot, the Life Skills students aren’t included in the educational sense at least, in “every aspect.” Even though they can join any club they wish and have the freedom to choose some electives, like choir, most core classes are taught “here at their level,” she said.

“Here” refers to a two-classroom block behind the cafeteria, complete with a row of lockers and decorated locker signs. One room houses the older students, while the other is home to the younger set. The classroom that caters to the older students is a colorful place, full of bright posters detailing the alphabet or number system.

However, based on Caleb’s ability, he takes a core class outside of the Life Skills rooms. He still spends SRT and four other periods in the Life Skills area, but in Ellery’s class, he completes tests and assignments at the same time as his general education peers. The content is modified to fit his ability, but “they’re easy,” Caleb said.

According to Ellery, “From day one, he has just been another student in the class. Behaviorally and interactively, he’s just like another student. They look at him to be a presidential authority, and he is.”

Educationally, then, Life Skills students are included to the best of their abilities. But even if the lawmakers and teachers work together to educate these students in the most inclusatory manner possible, not all aspects of the high school experience can be controlled—especially the social aspect.

Inclusion’s Effects

For Caleb’s mother, Karen deBoer, inclusion at the high school is “a mix” of the positive and negative aspects of both dimensions. “Is high school better?” she said. “It’s not worse. It’s definitely better (than junior high). But if more people were friendlier, I think that would help. I think the kids still possibly get ignored… being sort of invisible is sad for them.” Even so, Mrs. deBoer said that she is “thankful” for the volunteers who help in the Life Skills area and praised the Best Buddies program, an organization that works to fully include Life Skills students.

She said that she’s also glad that Caleb, now 18, will stay until the day before his 22nd birthday. “(Here) he’s learning what applies to him. He’s not able to go to college, so they let him stay at the high school. It gives him the opportunity to have more social interaction for a few more years to work on some things he might need help with. I’ve been very happy that Caleb has had to take a large variety of classes. I think it’s terrific that he can be in (Ellery’s) history class.”

The Life Skills program here even extends beyond the classroom, as the school bus takes Caleb to the Regal 17 Movie Theater at 2 p.m., where he works until 8, sweeping up popcorn and adjusting arm seats. “(The job) is a real blessing,” Mrs. deBoer said.

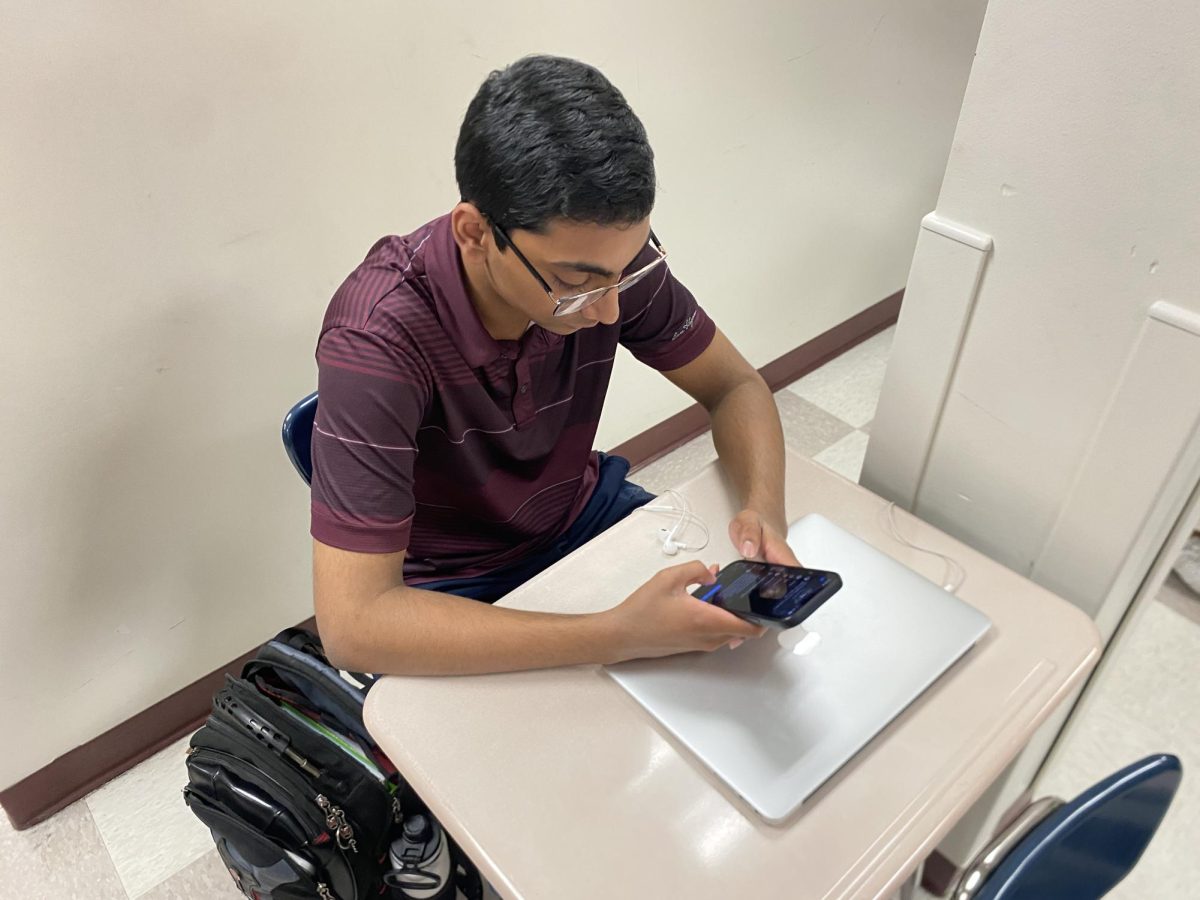

Caleb said all of his friends are also in Life Skills. “They’re fun,” he said. But of his social interactions outside the colorful classrooms, he said, “I don’t feel included. I wish (students outside of Life Skills) would talk to me. They don’t know me perfectly well. I don’t know them all very well. They look at me that I know my presidents.”

Ellery said that he doesn’t think it’s unusual that Caleb feels that way. “(Caleb) may just be a little more honest than others,” he said. “If you ask a student ‘Do you feel completely included in school?’ he’d say no.”

But Taylor Stout, president of the Best Buddies program and senior, said that she wishes all students would be included in every way. “Out of a one to 10 rating, I’d rate the inclusion here at eight. I wish (the Life Skills students) had a locker next to mine. I wish it was a 10. Sometimes people make fun of them. I just want everyone to accept them as friends and equals.”

“People aren’t going to associate with (the Life Skills students), because they don’t have any classes with them,” Mrs. deBoer said. “That’s normal.”

But Smoot said that the school system takes every opportunity to include the Life Skills students, even including them in the Homecoming festivities. For the dance, the students used a stretch limousine from the restaurant to the school. That image of the 20 or so smiling faces in front of the limo is now Smoot’s computer screen saver.

They’re present at convocations; they sit on a row of metal stands above the varsity gymnasium bleachers. In the convocation before the State game, they cheered with the mass of blue-and-yellow-clad students. A group of teachers sat with them. The celebration included the students, but the rest didn’t interact with them as the mass of dismissed peers surged past.

Many ride the bus, but they leave to board them a few minutes before the thousands of others do. They also eat in the same cafeteria as the rest of the students, but “they still sit together,” Stout said.

But even if Caleb’s friends are almost entirely from this crowd, he said, “No, I’m not sad. I’m happy.” Pointing to the colorful classroom, which he calls his school, he said, “My friends are here.” He added, “I wouldn’t change anything perfectly at all. I feel great. I feel comfortable. I’m perfectly protected.”

![British royalty are American celebrities [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Screenshot-2024-03-24-1.44.57-PM.png)

![Review: “Suits” is a perfect blend of legal drama and humor [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/unnamed-1.png)

![Chelsea Meng on her instagram-run bracelet shop [Biz Buzz]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_2446-1200x838.jpg)

![Review: Quiet on Set: The Dark Side of Kids TV is the long awaited exposé of pedophilia within the children’s entertainment industry [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/unnamed.jpg)

![Review: “The Iron Claw” cannot get enough praise [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/unnamed.png)

![Review: “The Bear” sets an unbelievably high bar for future comedy shows [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/unnamed.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: When I Fly Towards You, cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie, departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: Hidden Love is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: Heartstopper is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)

![Review: Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie, departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster-221x300.jpg)

![Review: Next in Fashion season two survives changes, becomes a valuable pop culture artifact [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Screen-Shot-2023-03-09-at-11.05.05-AM-300x214.png)

![Review: Is The Stormlight Archive worth it? [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/unnamed-1-184x300.png)