Over a year ago, the U.S. Supreme Court made a decision that transformed the face of college admissions: the banning of affirmative action. Melinda Stephan, College and Career Resource Center (CCRC) coordinator, said it’s important to recognize how affirmative action was used in a broader sense.

“Essentially, affirmative action aims to increase and improve diversity, not just on college campuses and with race, but that’s how people know it to be used in particular,” Stephan said. “That definition also expands to gender and socioeconomic status; any underrepresented status could be considered as part of the admissions process.”

But with that status no longer being considered, it changes how some students view the admission process. For example, although the program was controversial, senior Justin Macharia said affirmative action allowed minorities to have opportunities they otherwise wouldn’t have.

“In the context of college applications, affirmative action was a way for minorities who weren’t provided the same amount of opportunities as other groups to have a level playing field,” Macharia said. “A lot of minorities might not go to a good school that offers AP classes or have the best teachers that can teach them calculus. Their applications should be considered based on the opportunities that they’re given.”

Senior Amna Ahmad said bias in admissions has historically been an issue, specifically one targeting minority groups.

“From my understanding of affirmative action, it was a program that helped minorities get into college, rather than institutions forcing bias upon those groups,” Ahmad said.

Similarly, Macharia said affirmative action worked to eliminate bias and was beneficial when in practice.

“Every college says otherwise, but realistically, there’s some inherent bias in the admissions process,” Macharia said. “When someone reads your (application) and essays, they can get a picture of who a person is and what they look like. I think affirmative action was a good thing, especially considering some colleges practice legacy admissions, which doesn’t translate into actual academic ability.”

Without the program, Stephan said some were concerned regarding diversity and accessibility of admissions.

“After the Supreme Court decision that struck the ability to officially use race or other underrepresented status, there was talk on both sides,” Stephan said. “Admission people seemed worried that it would make it harder to build that diverse class. It also caused some fear and trepidation on the part of the students who felt their whole story wasn’t going to be considered. I’ve seen some data, which may be unofficial, that fewer underrepresented students applied to certain schools and fewer were admitted.”

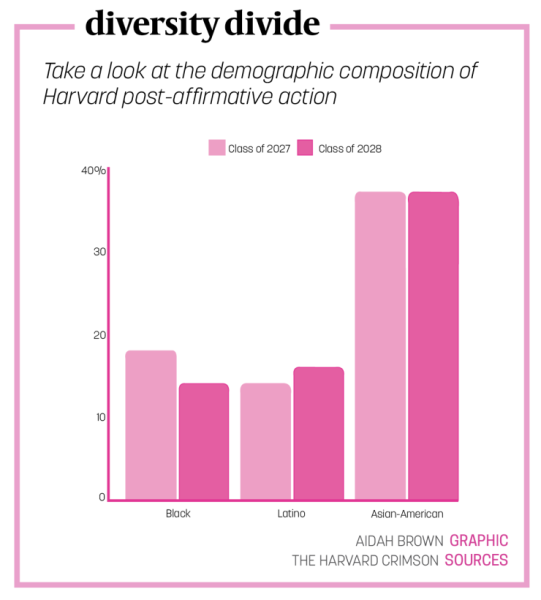

As Stephan said, data shows these fears were not without bias. According to a 2024 tracker of 50 selective schools by Education Reform Now, Black enrollment is down at three-quarters of the schools included. Differences in diversity of schools post-affirmative action varied greatly from school to school.

Regardless, senior Iniyaal “Ren” Sethupathi said the banning has negatively impacted the college landscape.

“I think the banning (of affirmative action) was a step in the wrong direction,” Sethupathi said. “Our education system is already disadvantageous to minorities from the start, especially socioeconomically. We can’t look at socioeconomic disadvantages without factoring in race. By disadvantaging people from the very beginning, affirmative action was trying to remedy that in the education practice. Now there are less Black and Latino students on campuses and it puts this paywall to higher education.”

Ahmad said it’s important to acknowledge other groups who may be disadvantaged in the admissions process.

“The divide here goes into socioeconomic status too,” Ahmad said. “Black and Latino people are systematically disadvantaged, which contributes to this. If you look at Black and Latino students from wealthy backgrounds, they probably will not be affected by affirmative action as much because they have access to those resources. On the other hand, poor Asian and White people probably still have lesser chances of admission due to the lack of resources.”

Like Ahmad, Stephan said the admissions process may be difficult to navigate for many, and other factors besides affirmative action could help.

“To improve diversity on campuses, we could consider taking away the barriers of the application process,” Stephan said. “This is more tied to finances than to underrepresented status, but sometimes those go hand-in-hand. It’s expensive to apply to college, even making that application free could help. Also, there are studies that show standardized testing is somewhat biased toward a particular demographic. The whole test optional movement could help with that bias”

The National Education Administration recognizes potential bias in standardized testing, also claiming bias due to societal realities. To combat bias, Macharia said it is essential to continue promoting diversity.

“Diversity is so important,” Macharia said. “At Carmel High School, our student population is mostly white because of the area. A lot of people have a jaded view of reality because they’ve been here so long and haven’t seen any other cultures. Universities and colleges should try to have a diverse student body, and not just through racial diversity.”

Although many are concerned about diversity, Stephan said the reaction from students here has been unexpected.

“I haven’t had many students come to me and directly say they’re concerned about the affirmative action decision,” Stephan said. “I was bracing for it, but it didn’t seem to happen. Most students come to me for essay help, which allows me to see changes in the essay prompts, which now ask students to share their unique stories.”

Similarly, Ahmad said the essays pose an opportunity for students to embrace their culture and identity.

“Minority students should talk about their culture if it impacts who they are,” Ahmad said. “Overall, staying true to yourself is the most important thing throughout the process.”

Likewise, Macharia said minority students should not shy from telling their unique stories.

“I think students will lean more into their ethnic backgrounds,” Macharia said. “There’s no ban for talking about your race, where you came from or how you grew up. That’s a very important part of who you are, especially when you’re trying to tell a random person on the other side of a screen who you are.”

On both the admissions and student side, Stephan said a deeper understanding of the process, including the flaws and helpfulness, must be strived for.

“It’s not just about checking a box on an application about what your race or gender or status is,” Stephan said. “Ultimately, we need to think of the (application and admissions) process and how we can make it easier for underrepresented groups to get through it.”

![AI in films like "The Brutalist" is convenient, but shouldn’t take priority [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/catherine-cover-1200x471.jpg)

![Review: “The Immortal Soul Salvage Yard:” A criminally underrated poetry collection [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/71cju6TvqmL._AC_UF10001000_QL80_.jpg)

![Review: "Dog Man" is Unapologetically Chaotic [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dogman-1200x700.jpg)

![Review: "Ne Zha 2": The WeChat family reunion I didn’t know I needed [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/unnamed-4.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)