Senior Rachel King is well aware of her limitations. Where other students may not think too much about sitting down and typing on a computer, she has to consider what her body will and will not let her do.

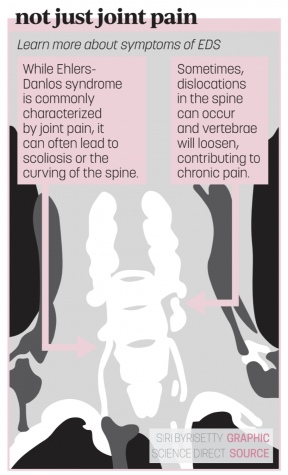

“I can’t do certain things or my fingers will dislocate, that’s something that happens a lot,” King said. “I can’t type super fast because then my pinkies will dislocate. I can’t run or jump or do anything like that either.”

King has Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), a disorder that commonly affects the joints, skin and blood vessels. EDS is one of many illnesses classified as an “invisible disability.”

The Invisible Disabilities Association defines an invisible disability as a physical or neurological condition that is not visible from the outside yet still limits a person’s movements, senses or activities. King said she agreed with this definition.

“I can’t stand up for long periods of time, and I also have to move around a lot or else my joints will get locked up and it’ll be really hard to move them,” King said.

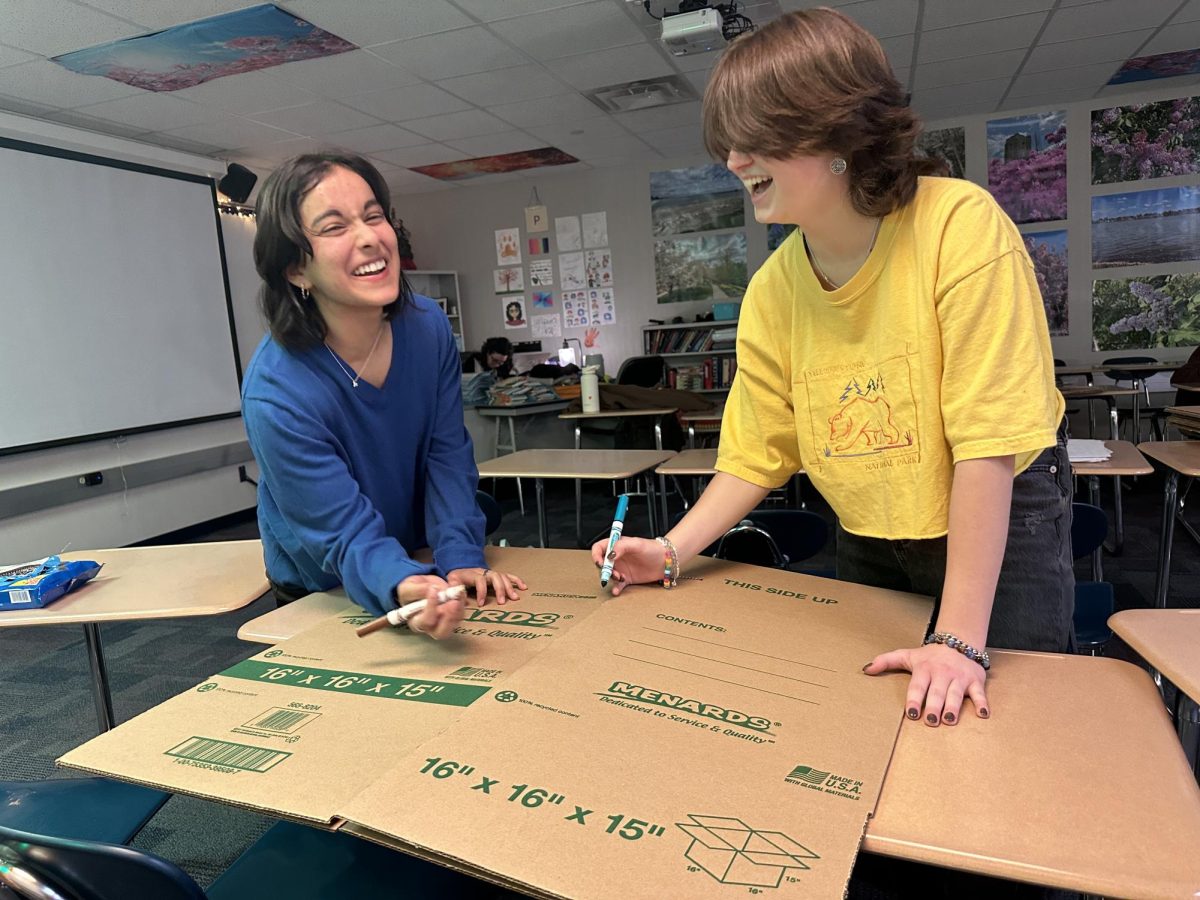

Junior Francesca Gobbi-Belcredi, who was also diagnosed with EDS, agreed that it greatly affects her life. Like King, Gobbi-Belcredi said she has to constantly think about what she’s capable of doing.

“With EDS, you can’t do everything that most people can do,” Gobbi-Belcredi said. “I can’t go for a run because I worry that my knee will dislocate…You just have to think about things like all the medicine I take; I can’t miss any of that. I have to stay extra hydrated because I could pass out. You just have to think about things that most people don’t have to.”

In school, Gobbi-Belcredi and King said they have accommodations that allow them to get to where they need to be.

“At school, I use elevators because it’s harder for me to use stairs,” King said. “I get to leave 10 minutes before (the bell rings) if my class is across the school, so that gives me some extra time because I can’t walk super fast.”

Gobbi-Belcredi said her needs change day-to-day. “I have an elevator pass, I keep a textbook in each of my classes and bring one home…I have a parking pass so I don’t have to walk from stadium parking,” she said.

Both students said they felt supported at school but did note areas where the school could improve. One accommodation Gobbi-Belcredi and King use are the school elevators, and they both said the elevators are not reliable.

“Some of (the elevators) are honestly scary,” Gobbi-Belcredi said. “There was one last year where there was a literal hole in the elevator door…they’re not trustworthy. My freshman year I got stuck in the freshman elevator five times.”

King said she agreed the elevators were unreliable and slow.

King also said there were some individual circumstances that made it harder for her to get around.

“Not everybody knows about (my disability), so…trying to find a way for me to get picked up without having to walk down the trail, that was a big deal,” King said. “My mom was getting yelled at by all the bus drivers and that was a whole thing. She had to hold up a sign saying, please, my daughter’s disabled.”

To develop the specific accommodations they need, Gobbi-Belcredi and King have 504 plans. 504 plans are formal plans schools create to support students with disabilities. Assistant Principal Maureen Borto explained how the administrators here works with students with disabilities.

“Our approach for any kid is no different, whether (their disability) is visible or invisible,” Borto said. “We follow whatever the recommendations are based on someone’s doctor. So if it’s a physical illness, then we (consider)…the doctor’s recommendations, and then we work based on those to provide accommodations.”

King said she believed the school does a good job of accommodating her needs.

“I haven’t had any issues (with the administration) and I’ve been able to get (the accommodations) I need to get around and do what I need to do.”

Gobbi-Belcredi said the school was understanding that she didn’t always need to use her accommodations.

“Some days I’ll need (the accommodations) and other days I won’t,” Gobbi-Belcredi said. “They’re understanding with that, they don’t expect me to have to use them every single day.”

King said her varying abilities often caused people to doubt her disability.

“It’s kind of difficult because people will question, ‘Why is she in a wheelchair if she can walk? Why is she using the elevator if she can technically go up stairs?’ It’s difficult because I feel like people don’t really believe you or (think) that anything’s wrong with you, and they believe that you’re faking it,” she said.

Gobbi-Belcredi said she agreed. She said on days when she’s feeling capable, people will think she’s faking because she’ll seem able-bodied.

“Those are the days when people automatically think, ‘Oh, she’s faking’ because one day I’ll be on crutches because I can’t walk and the (next) day I’ll be fine,” Gobbi-Belcredi said. “But also, teachers, they automatically are like, ‘Oh, you’re not allowed to carry your backpack’ or, ‘Oh, you shouldn’t be standing up to do a lab,’ and on the days when I’m capable of doing those things I’m not going to have other people help me. If I’m capable of it, I’m going to do it myself, but people don’t tend to understand that.”

King said she wasn’t diagnosed with EDS until she was 16, and she said she used to experience internalized ableism before she understood her disability.

“I used to think I was faking it, like, ‘Oh, you’re just doing this to get attention’ even though my knee would be out of place,” she said. “I went undiagnosed for a really long time so my family did think I was faking all the pain that I was in, all the dislocations I was having.”

undiagnosed for a really long time so my family did think I was faking all the pain that I was in, all the dislocations I was having.”

Gobbi-Belcredi said she also went undiagnosed for a long time, and she said she believed that was because invisible disabilities weren’t treated seriously enough in the medical field.

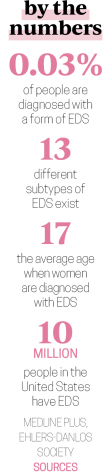

“I was searching for an answer for five years before I was diagnosed; I was diagnosed when I was 14,” she said, “but I was looking for answers since I was 8 or 9 because that’s when my knees and shoulders started to hurt. People told me it was growing pains—it’s not growing pains. (EDS) is actually not that rare but doctors completely forget about it so it’s rare to be diagnosed with (EDS) but it’s really not that rare to have.”

According to MedlinePlus, 1 in 5,000 people have some form of EDS. Jameela Jamil, British actor and activist, spoke out about her EDS diagnosis in an attempt to raise awareness and encourage more research about the disorder.

“It’s terrifying how many doctors still haven’t heard of it,” Jamil said in an interview with the Ehlers-Danlos Society. “So many people have (EDS), and so many more people than we realize (have it) as they don’t know the symptoms, because the symptoms aren’t being discussed on mass.”

King said she agreed there were many people who didn’t realize they had a disability.

“Especially with invisible disabilities, diagnoses are difficult to come across,” King said. “It took me 16 years to get a diagnosis for something that isn’t super hard to diagnose.”

Gobbi-Belcredi said she wanted more people to know about EDS.

“I’ve started to get better so people don’t necessarily realize I have (EDS) anymore. It’s a true invisible disability now,” she said. “But if you know me, you know I have EDS. I think more people need to become aware of it because people don’t realize how many people are affected by it.”

Despite the difficulties, Gobbi-Belcredi said her disability was a part of her, and she wasn’t ashamed.

“Obviously (EDS) affects me, but I try not to let it mentally affect me,” Gobbi-Belcredi said. “I just think about it like I’m unique…I don’t think about it as an issue I have, I think about it like it’s part of who I am and I can’t change that, so I shouldn’t try to.”

![AI in films like "The Brutalist" is convenient, but shouldn’t take priority [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/catherine-cover-1200x471.jpg)

![Review: “The Immortal Soul Salvage Yard:” A criminally underrated poetry collection [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/71cju6TvqmL._AC_UF10001000_QL80_.jpg)

![Review: "Dog Man" is Unapologetically Chaotic [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dogman-1200x700.jpg)

![Review: "Ne Zha 2": The WeChat family reunion I didn’t know I needed [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/unnamed-4.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)