In October of 2013, Forbes chose Russian president Vladimir Putin as the world’s most powerful man.

In October of 2013, Forbes chose Russian president Vladimir Putin as the world’s most powerful man.

About two seconds after writing that sentence, I shifted my weight, knocking my hand into a pencil and sending it flying downward.

What do these two events have in common? Not that much, admittedly. Putin is known for strong-arm control of Russia’s domestic and foreign policy and strong arms in outdoor photo opportunities. My pencil is known for poor handwriting during timed essays and poor flexibility when it snaps like a twig. However, in the moment it was hurtling towards the ground, it had at least one thing in common with Putin. Something Putin knows how to harness.

Kinetic energy.

The trade-off between kinetic and potential energy is an interplay that governs infinite facets of our lives. A stationary object—in this case Russia—has potential energy—in this case its relation to a peace-desiring world that’s dependent on its energy exports. If this object is set in motion it loses potential energy but gains kinetic energy, enabling the moving object to impart force on other objects.

Russia theoretically may not be the most stable pencil in the pencil case. Looking at Russia’s economic tanking after years of energy export over dependence, or its high levels of corruption or its internal ethnic unrest, it shouldn’t be able to twist the arm of the international community like it’s doing now. That is, unless Putin knows how to maximize whatever diplomatic leverage he can generate without putting himself at a disadvantage.

When he annexed Crimea, sure, the international community vilified him, but what else could it do? Tariffs are out of the question. As Germany conveniently pointed out, over 36 percent of its energy imports are from Russia, a situation paralleled throughout Europe. Dependence on Russian energy exports proved too great to simply cut off at the tap, leaving European countries no choice but to adopt a more conciliatory stance. With this option stifled, where does the United States have to turn?

Other forms of intervention the United States can take are discouraged by continuing isolationist tradition and memories of the Cold War. For example, in December of last year the Pew Research Center found that American support for isolationism has reached a 50-year high. If our own people recoil from international involvement, this means most forms of American intervention are out of the question. With this near stupid level of diplomatic entanglement (the “potential energy”) Putin has found himself free to impart his “kinetic energy,” go into Crimea and do virtually whatever he pleases, knowing that everyone will be hapless to stop him. His ability to take advantage of this situation earns him the title of “the world’s most powerful man.”

Some may say that this alone does not grant him the status as the world’s most powerful man. Some may say that Crimea is an isolated affair and holds little economic or political importance and that the leader of a more stable, more economically viable country deserves this title. The President of the United States, perhaps? However, while Barack Obama may wield the power of one of the most powerful countries in the world, it is what he chooses to do with that power on a world stage that determines its status. If Obama balks, it is Putin who ultimately comes out the winner. Here, Putin is able to get the acquisitions that Russia wants while ensuring that relative peace is kept. If he decides to apply this brinksmanship to future international affairs, what’s to stop him?

Crimea may be an isolated affair, but if Putin decides that this style of foreign policy is his sort of gig, he could easily use it elsewhere, knowing that, in nearly every scenario short of razing Switzerland to the ground, diplomatic entanglement will enable him to get at least some concessions. It is important to see that it is not the power of Russia that justifies Putin as the world’s most powerful man, but his foreign policy and the conciliatory stances of other nations.

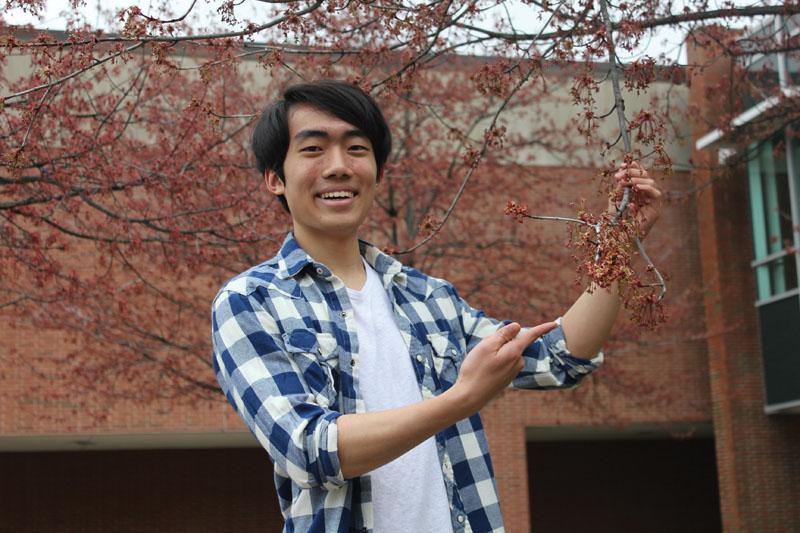

The views in this column do not necessarily reflect the views of the HiLite staff. Reach John Chen at jchen@hilite.org.

![What happened to theater etiquette? [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Entertainment-Perspective-Cover-1200x471.jpg)

![Review: “The Immortal Soul Salvage Yard:” A criminally underrated poetry collection [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/71cju6TvqmL._AC_UF10001000_QL80_.jpg)

![Review: "Dog Man" is Unapologetically Chaotic [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dogman-1200x700.jpg)

![Review: "Ne Zha 2": The WeChat family reunion I didn’t know I needed [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/unnamed-4.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)