Although he goes to a different synagogue, junior Josh Honig said the hate crime on Congregation Shaarey Tefilla (CST) was a wake-up call.

On July 28, burn marks and anti-Semitic graffiti, comprised of Nazi flags and iron crosses, were discovered at CST, engendering a wave of support for Jews in the area.

“People think of (Carmel) as a fairly safe place, but it brought to attention that there are definitely people who wish to do harm,” he said.

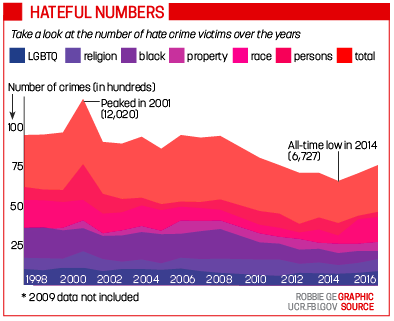

With crimes like these, as well as the shooting at Tree of Life Congregation Synagogue in Pittsburgh on Oct. 27, many Hoosiers are reevaluating the need for stricter hate crime legislation. According to the FBI, a hate crime is a traditional offense, like arson or vandalism, with the added motivation of a bias against race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, ethnicity, gender or gender identity.

Indiana is one of five states without a law specifically addressing hate crimes. The existing law, passed in 2000, states that it is Indiana’s policy to prosecute crimes equally, regardless of the motivation behind the crime. CST rabbi Benjamin Sendrow said he has mixed feelings regarding the idea of a hate crime law.

“(If a crime is) committed against a Caucasian man, and the exact same crime is committed against an African American man, the punishment should be the same, so there’s a part of me that says make all the punishments stiffer,” Sendrow said. “On the other hand, the guy who defaced our synagogue, if it weren’t for his violating federal civil rights laws, the crime would have been misdemeanor vandalism.”

According to Indiana Code Title 35, the vandalism, which would have otherwise been a Class B misdemeanor, was classified as a Class A misdemeanor because it was damage to the synagogue, a structure for religious worship. This translates to up to a year in prison with a maximum fine of $5,000. However, in a state like New York that does have a hate crime law, that same Class A misdemeanor would be deemed a Class E felony, which could mean two to five years in jail, potentially five times longer than in Indiana, according to NY Criminal Defense.

“I feel like (a law addressing hate crimes) would be a deterrent of sorts, maybe a deterrent to people who wish to do hate crimes,” Honig said.

Disregarding the opposing views about the legislation, Sendrow said it was the waves of attention following these hate crimes that made an impact.

“They tried to frighten us, but all they did was create an outpouring of love and respect, so they absolutely failed at what they wanted to do,” Sendrow said.

World history teacher Katie Kelly said these waves of support began with the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s, in which civil rights leaders worked to show people how they were being treated.

“There were movements throughout the country of people saying, ‘This isn’t right,’” Kelly said. “That did lead to an outpouring of support, and I think that has continued on.”

To illustrate, two days after the synagogue was defaced, it hosted a solidarity rally. According to Sendrow, over 1,000 people squeezed into the synagogue, with hundreds more outside to the point where police had to turn cars away.

“Our parking lot, University High School’s parking lot, West Park’s parking lot, and all of the neighborhoods around us. The streets were full,” he said. “And the people came from every facet of the community you could imagine: Jewish and Christian and Muslim and Buddhist, black, white, Asian, straight, gay. I cannot think of a group of people who was not represented there. It was the most powerful thing I’ve seen in a very, very long time.”

Sendrow said the Pittsburgh attack has evoked a similar response, as 400 miles away from the Tree of Life Congregation, a synagogue in Indianapolis hosted an event in honor of the 11 worshipers who lost their lives. Around 2,000 people attended that ceremony, namely members of Congress, senators and the mayors of Carmel and Indianapolis.

According to Kelly, depending on the motivation, committing a hate crime often does not evoke the intended response.

“More people are going to support the Jewish community because they realize that this is a group that’s being persecuted,” Kelly said.

But Honig said people still need to take action.

“(The vandalism) was probably somebody just screwing around, but this is still an issue. This hasn’t gone away yet, and it won’t,” he said.

In the end, Honig said the incident did not affect him much personally even though he is involved with the Jewish community because an individual committed the crime.

Sendrow conveyed a similar idea.

“The acts of a few people do not define our area, our state, our country,” he said. “Our country is full of wonderful, warm, loving (people). They’re respectful of other cultures; they’re respectful of other religions. That’s Indiana. That’s America. We can’t let these few bad actors define our society. They are the aberration. They are not the norm.”

![What happened to theater etiquette? [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Entertainment-Perspective-Cover-1200x471.jpg)

![Review: “The Immortal Soul Salvage Yard:” A criminally underrated poetry collection [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/71cju6TvqmL._AC_UF10001000_QL80_.jpg)

![Review: "Dog Man" is Unapologetically Chaotic [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dogman-1200x700.jpg)

![Review: "Ne Zha 2": The WeChat family reunion I didn’t know I needed [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/unnamed-4.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)