When sophomore Adama Barry had a conversation with her friends, she was surprised to find they also occasionally felt stuck between two worlds and didn’t feel understood in either.

“I’m Guinean, I’m from West Africa. We have a really deep culture and it’s way different from American culture here,” she said. “I feel like when I was younger there was a disconnect (between these cultures). It can really affect how you see yourself. Like, once your self-perception is warped, you don’t really know who you are, or (you) are trying to be something else you’re not.”

Barry is not alone. Freshman Paulina Arana Cervoni echoes these same sentiments.

“I feel like my two worlds are kinda mixed together as one,” she said, “but it can be really hard sometimes. Like, I can speak Spanish (but) I’ll forget words, I can feel kinda guilty about that. I feel really lucky though because I have a lot of Puerto Rican friends here but sometimes I still feel like there’s a disconnect between my friends and me, as well as my family and I.”

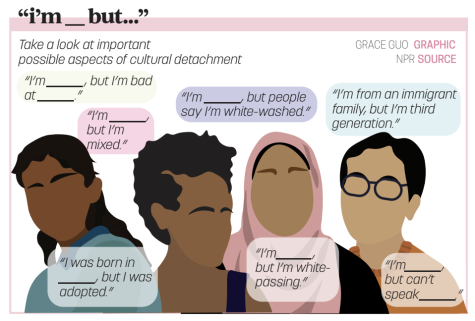

Arana Cervoni and Barry both experience something called cultural detachment. CCS Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) Officer Terri Roberts-Leonard defined cultural identity via email.

“Cultural identity refers to identification with, or sense of belonging to, a particular group based on various cultural categories, including nationality, ethnicity, race, gender and religion,” Roberts-Leonard said. “Cultural identity is constructed and maintained through the process of sharing collective knowledge such as traditions, heritage, language, aesthetics, norms, and customs.”

The phenomenon of cultural detachment is often referred to as racial imposter syndrome. According to the BBC, racial imposter syndrome is defined as when one’s internal sense of self doesn’t match with others’ perception of their racial identity, which gives rise to a feeling of self-doubt. The Interaction Institute for Social Change (IISC) clarifies that racial imposter syndrome is deeply intertwined with assimilation and racism. This cultural disconnect most commonly occurs in first-generation Americans and multiracial people.

“I’ve seen a lot of people kind of assimilate or whitewash themselves and I get it,” Barry said. “People made them feel less than they were or people made them feel ashamed of who they were, so they felt like they needed to change themselves to be better or to be liked. I think I like who I am even when it’s not as digestible because of my culture.”

Arana Cervoni said she agreed. She said she sometimes acts differently depending on who she is around.

“I don’t do it that much anymore,” she said, “but I still act differently around my Puerto Rican friends versus my other friends. I think sometimes it’s just easier to act differently. I was still me, just kind of (a) different version.”

This behavior is known as code-switching, a behavioral practice people from marginalized groups engage in to assimilate to the at-large culture. However, according to an article from the Harvard Business Review titled, “The Cost of Code-switching,” code-switching can be detrimental to a person’s mental health and self-perception. The IISC also stated racial imposter syndrome involved “losing a sense of self,” which can lead to feelings of guilt or being misunderstood.

Arana Cervoni said she has been criticized for doing normal Puerto Rican practices.

“There have been times where I have gone out and been too loud or too Hispanic and have gotten bad looks from others,” she said. “I have been judged for being too Puerto Rican or (for) doing certain cultural norms. It has affected me a little bit because sometimes it makes me feel very out of place.”

Barry said, often, culture is not stigmatized but fetishized. She said she has seen teachers talk about racism as a thing of the past, while ignoring modern microaggressions.

“Sometimes they see other people as exotic,” she said. “It’s almost trendy, and if it’s being overly fetishized it’s almost like you don’t want to be a part of that (culture) anymore.”

Barry said she also hopes to see more discussion about cultural identity and race.

“I think the majority of people feel uncomfortable talking about (racial identity) because it does bring up a lot of other topics that people just don’t want to talk about,” she said. “But it’s something we do need to talk about because these problems are affecting us in a really negative way, and we need to get past them so we can create a better community in our school.”

Roberts-Leonard said CCS hasn’t addressed racial identity as much as she would like to, but progress is underway.

“I can speak for Carmel Clay Schools in saying that CCS recognizes the need to do more work in this area, hence the creation of my position as well as committees at various levels throughout the district,” Roberts-Leonard said. “I work with individuals and groups on looking at ways they can make their school buildings more inclusive and welcoming to all. For example, examining current policies, practices, and traditions to ensure they are inclusive and equitable. It is a big job and we are building a plan to be strategic in our approach. We have a strong focus right now on learning about the importance of inclusive environments and educating ourselves on the various cultures that we have throughout the district.”

Both Barry and Arana Cervoni said they agree their culture and identity have not always been accepted by others. However, they said they refuse to let that stigma affect their behavior.

“(People have) sometimes made me feel ashamed for being Puerto Rican, but it has truly shown me that people are going to stare no matter what,” she said. “You are going to be judged by people for everything you do, so you may as well do whatever you want and be whoever you want to be. It has shown me that I should never be ashamed for being the ‘loud Latina.’”

![What happened to theater etiquette? [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Entertainment-Perspective-Cover-1200x471.jpg)

![Review: “The Immortal Soul Salvage Yard:” A criminally underrated poetry collection [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/71cju6TvqmL._AC_UF10001000_QL80_.jpg)

![Review: "Dog Man" is Unapologetically Chaotic [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dogman-1200x700.jpg)

![Review: "Ne Zha 2": The WeChat family reunion I didn’t know I needed [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/unnamed-4.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)