CLC provides project-based path to graduation

After spending around two weeks at CHS, junior Ella York transferred to the Carmel Learning Center (CLC), an alternative education service across the street from the high school. As a new student at CCS, York said she heard rumors about the smaller school and didn’t think much of it.

“When I was going over there, when I was walking in,” she said, “my mindset was, ‘This is going to suck.’”

York said she quickly realized she was wrong.

“When I (first) walked in, this one girl was just so nice to me,” she said. “Everyone was just the opposite (of what I thought).”

Drew Grimes, director of the CLC, said he knew about the CLC’s reputation and disagreed with the rumors. Rather than a problematic place for problematic kids, Grimes said the CLC is catered to students who need a different environment for learning.

“I think there’s a misperception…about who we are (at the CLC) and who our kids are,”

Grimes said, “We have 20-something kids and they’re all there for 20-something different reasons. Some kids needed a different pathway, a different learning environment. For some kids it has to do with their need to work; there’s home-life situations where they need to work more. (And for) others, I mean, 5,000 kids in a building for some is too much. It’s too overwhelming. No two experiences are the same; we’re there to provide a different pathway.”

To create a more helpful environment, Grimes said the CLC lets students work and take classes at their own pace.

“We try to put the kids in the driver’s seat as much as possible…We have two sessions, a morning session and an afternoon. Our students only have to come for three hours a day with the expectation that the other part of the day is (productive),” Grimes said. “(And) instead of giving a kid all seven to eight classes at once, sometimes we’ll just go, ‘Hey, let’s just work on two or three’, that usually helps kids move along pretty quickly. ”

Another contrast from the traditional high school class, is the CLC implements project-based learning.

“We ask (all the kids) to do some projects. It’s more high-interest,” Grimes said. “Whatever (students’) interests or passions are, we really try to bring that out in what they do. That’s what we design the projects around. We try to clear the path.”

York said she believed the projects were helpful and allowed her to connect with her learning more.

“For me, I really enjoy writing,” she said. “With certain kids, they’ll do more question-based (projects), (but) for me they gave me more essay-like things to complete for English. They’ll lay out different options, and (I’m) still getting the learning process of it all, (I’m) just getting to choose (my) own path to make sure it doesn’t feel forced. It takes some of the busy work out of it and being able to write something (I’m) proud of or interested in makes a huge difference.”

Grimes said his goal was to make sure his students were proud of the work they completed. He said the project-based learning lets students use their passion and creativity to connect with their education.

“In the afternoon (session), I had a young lady who thinks someday she might want to be a tattoo artist,” Grimes said. “We read some things for U.S. history—some first-person accounts of a war—and she designed an arm sleeve. (She) drew out on paper what it would like and what (symbols) represents what, and that was her final project for that class, (doing) something she’s interested in.”

York said the staff and environment of the CLC made learning easier, but not meaningless.

“It’s not just lazy work,” she said. “You’re learning and it’s not like you’re just on a (smooth) path. (The teachers) make it smoother, but you’re still (learning). I know when I went over there people were like, ‘Oh, you’re just going to get easy credits,’ but it’s not easy credits; it’s making me connect with the work.”

Grimes said his goal was to get rid of the busy work and let students use their time efficiently to develop the skills they need for the future.

“That Mark Twain quote, ‘Never let schooling interfere with your education,’ that’s kind of my motto over there. Let’s get rid of the school and make sure we’re focusing on education,” Grimes said. “If you’re a college-bound kid, let’s make sure you have those reading and writing, those math skills. If you want to go right into the workforce, your experience might look a little bit different, your expectations might be a little bit different in what we’re gonna ask you to do and what we expect from your projects. We do have 20-something kids, they’re there for 20-something different reasons, and they’re doing 20-something different things. We just try to (make sure) every kid has the experience that they need.”

Math teachers receive grant to expand “Thinking Classrooms”

Over the summer, math teacher Dawn Laumeyer participated in a book study with others from the math department.

“(The book) was Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics,” Laumeyer said. “This author, (Peter) Liljedahl, did a lot of research on effectively teaching math, and he had a lot of good ideas.”

Math teacher Micki Outcelt originally organized the book study. She said she heard the administration was reading the book and wanted to learn more.

“I actually was motivated by (Assistant Principal Karen) McDaniel to start a book study,” she said. “That’s when I sent out the email to see what kind of interest we would have in the department and there were about 10 or 11 of us that actually met throughout the summer. We met on a weekly basis and it was a team effort…We were able to, as a group, discuss ways we were going to use the information from the book.”

Liljedahl is a professor of mathematics education at Simon Fraser University in Canada. In his book, he identified 14 specific practices for thinking that create “an ideal setting for deep mathematics learning to occur.” Outcelt said she and other math teachers were interested in the book because it was geared for math educators.

“A lot of the books that we read for educational ideas aren’t necessarily only geared (toward) math, it’s more of a general idea. So when this was geared around math, it makes it a lot more interesting for us (math teachers) because we know the research has been done in a math classroom. I don’t want to say it has more credibility, but it just makes things more applicable,” she said.

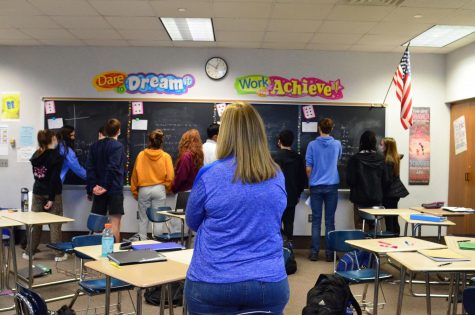

Laumeyer said she agreed. A major practice she incorporates from the research is the use of “vertical, non-permanent surfaces.”

“It’s whiteboards basically,” she said. “(Liljedahl) felt the magic number for groups was three (students). He said (to) get kids up and out of their seats, especially in the very beginning to get their brain activated, and do a five-minute task on the whiteboards.”

Outcelt said she also implemented vertical surfaces and groups of three in her classroom.

She said, “I use cards and I take out the number of cards I need (based) on the students that are missing and then I shuffle the cards and I spread them out on a table. The kids go up and get a card, and that’s the group that they go to. Most kids will take the randomization and welcome it, and meet new people, and they’ll all learn to work well together.”

The math teachers in the book study decided to apply for a grant sponsored by the Carmel Education Foundation (CEF) to buy more whiteboards and markers to apply more vertical spaces in math classrooms.

“It’s a lengthy process,” Laumeyer said. “You have to answer a bunch of questions, you have to justify your reasoning. How are we going to use that money? How does it help the kids? (Outcelt) was the spearhead on that one. She (got) ideas on what teachers needed so we can get enough money to purchase the whiteboards and markers and all the support materials we need to implement Liljedahl’s research.”

Outcelt said she believed the vertical spaces and whiteboards bought with the grant would help teachers and students. She also said she believed more teachers would use these strategies.

“There’s a lot of people that are using them just here in the A (halls). That’s one of the things I have to do (soon), is to order more boards,” she said.

Other than vertical spaces, Outcelt said she and the other math teachers also applied other tactics that were less obvious.

“Defronting the classroom (is one thing)…Although the screen is in the front of the room, when I’m talking to students I try not to stand in the front of the room. We have groups that are not even facing the front; that’s defronting,” she said. “The visual randomization is something the book also recommends because we want kids to know that we’re not placing them in a group on purpose. That it’s a safe group, a group that by chance you were put in. It’s not by ability level or behavior level..There’s a lot more than the major things you initially see, in what we do instructionally. ”

Laumeyer said she believed her students benefited from the thinking classrooms.

“I…like the idea of getting the kids up out of their seats because sitting there is just not conducive,” she said. “That’s one of the things I like about it, I’m not always up at the front of the classroom teaching all the time anymore. I get the kids up doing things, and I think that’s better for them and better for me too.”

Outcelt said she agreed. Overall, she said the thinking classrooms were better for the students and the teachers.

“I wanted something new and fresh, I wanted a fresh start especially coming out of…hybrid. In hybrid we just didn’t have discussions and I really missed it,” she said. “There’s a lot of us (math teachers) that are excited about what (the Thinking Classrooms) are doing for our rooms, and doing for our students. The dynamics of the room and the way that students are using the spaces, it’s encouraging.”

Peer tutors provide benefits for some

After junior Teresa Yu got her AP U.S. History test back, she signed up for a session with a social studies peer tutor to review her answers.

“(This) was (the) first time I ever used (peer tutoring),” she said. “I like (it) because the atmosphere is very comfortable and it helps me understand why I made a mistake and the overall thought process behind it.”

Yu said she believes she benefited from peer tutoring, especially one-on-one tutoring.

“One-on-one tutoring benefits me because it gives me time with a tutor to help me learn,” Yu said. “If I want to ask questions or take more time on a certain part, it’s much more comfortable and easier to do. The pace is very helpful (since) the pace is dependent on me.”

Junior Mindy Sim, the social studies peer tutor who walked Yu through her test, said she also believes peer tutoring can help students.

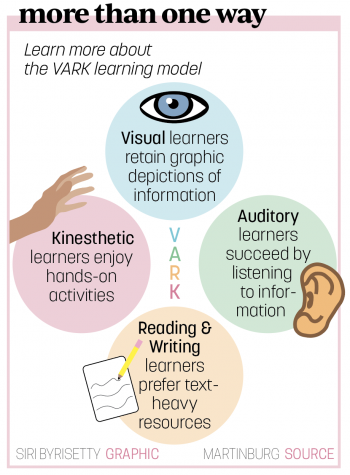

“Although I don’t know how peer tutoring actually impacts the grades of (the) peers that I tutor, I often get instant feedback about how certain content makes more sense after going over it together,” she said. “Everyone has different learning styles, but I think one-on-one peer tutoring can be beneficial to everyone because students can get more personal feedback on not only the content that they need help with but also on studying habits and test-taking skills.”

While peer tutoring is typically assumed to be beneficial for the tutee, research indicates the tutor can also profit. According to ResearchGate, peer tutoring allows the tutor to learn through reformulating their knowledge and allows the learner to receive one-on-one attention, both of which are beneficial. Sim said she agreed with this sentiment.

“Tutoring APUSH (AP U.S. History) while I’m currently taking the class is really helpful because I get the chance to explain the content to fellow classmates,” she said. “People often say that we learn best by teaching others and I think that’s accurate.”

As an APUSH tutor, Sim said she often talks her tutees through answers, which helps her connect more with the material.

“The nature of AP tests often means that I have to explain to someone why one answer is better than another, even though both may be historically accurate,” Sim said. “As I review answers to test questions and come up with explanations, I find myself having to form deeper connections within the history.”

Yu said peer tutoring was helpful as well as enjoyable.

“The peer tutors are really nice and take their time to explain things effectively,” she said. “I also think it is very useful just to talk with someone that understands the test and the class, (and is) open to answering any of your questions.”

On the other side of the table, Sim said she agreed. She said she liked meeting with her peers and learning more from them.

“I really enjoy peer tutoring because I get to interact with so many different peers. As I’ve tutored more, I’ve felt that I’ve also learned a lot beyond the content…which is very valuable to me,” she said. “At the end of each tutoring session, I try to ask my classmates about their study habits and just generally how they learn and review content for tests. Not only does this help me to expand my studying habits, (but) because of my peer tutoring position I can share these ideas with other classmates that I tutor in the future.”

![What happened to theater etiquette? [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Entertainment-Perspective-Cover-1200x471.jpg)

![Review: “The Immortal Soul Salvage Yard:” A criminally underrated poetry collection [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/71cju6TvqmL._AC_UF10001000_QL80_.jpg)

![Review: "Dog Man" is Unapologetically Chaotic [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dogman-1200x700.jpg)

![Review: "Ne Zha 2": The WeChat family reunion I didn’t know I needed [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/unnamed-4.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)