Sophomore Tejasvi Tadikonda cannot count how many names she has. Her name is pronounced THAY-jahs-vee, but people also call her T.J., TEE-jahs-vee and teh-JAWS-vee. On the first day of school, Tadikonda said she knows when teachers are about to read her name off the roster because they pause before attempting to pronounce it.

Because of the mispronunciations, Tadikonda said she hated her name. She said no one tried hard enough to say it right, and her name became a source of unease.

“When people would be like ‘Oh, what’s your name?’ I always have a sense of insecurity and panic,” Tadikonda said. “I’m like, ‘Oh my god, what do I say?’ because I have so many different names at this point, I don’t have one name true to myself.”

Many students share the same insecurities as Tadikonda. In fact, scientists have determined a phenomenon known as the “name-pronunciation effect;” people prefer names that are easier to pronounce over those difficult to pronounce. To draw attention to this issue, in 1997 American onomatology hobbyist Jerry Hill designated the first week of March as Celebrate Your Name Week, a time for everyone worldwide to embrace and celebrate his or her name. (Onomatology is the study of etymology, history and use of proper names.)

Additionally, to bring awareness to the importance of pronouncing students’ names, the Santa Clara County Office of Education (SCCOE) and the National Association for Bilingual Education launched the “My Name, My Identity” campaign in 2016. Yee Wan, director of the school climate, leadership and instructional services at the SCCOE, said schools should dedicate themselves to learning students’ names. Names, she said, are important.

“Students thrive in a place where they build relationships with each other and feel that they belong,” Wan said via email. “When you take the time to learn the proper enunciation, it lets the student know that you see them, that you respect who they are and that you value them.”

Junior Larine (pronounced LOR-en-ay) Casso said none of her teachers pronounced her name right on the first day of school.

“I’ve never had someone actually say my name right. I get Lor-ING a lot (and) LARE-en,” Casso said. “After the first time (a teacher mispronounces my name), I don’t really correct them. I’m so used to it right now that I just kind of ignore it.”

However, English teacher Linka (LINK-ah) Pace said she hopes students will correct teachers when they mispronounce a name.

However, English teacher Linka (LINK-ah) Pace said she hopes students will correct teachers when they mispronounce a name.

“I hate it (when students don’t correct me),” Pace said. “I mean, I think your name is part of your identity and I want to make sure I know who all my kids are.”

According to a study led by Rita Kohli, associate professor in the education, society and culture department at the University of California, Riverside, when teachers mispronounce a student’s name multiple times, it influences that student’s sense of identity. Along those lines, Tadikonda said the way people mispronounced her name made her feel disconnected from her Indian culture.

“Calling myself not my real name—like my nicknames like T.J., teh-JAWS-vee or whatever—it kind of washed away part of my culture,” Tadikonda said. “I did not want to be Indian at some point because (my name) affected me so much, (and) people made fun of me that much.”

On the other hand, freshman Savneet Dulay (pronounced sav-NEET du-LAY) said she does not let other people influence her identity.

Dulay said, “(Other people) are not me. They don’t know who I am, so I’m not going to take in their judgement (of my name.)

Regardless, Pace said she tries to pronounce her students’ names correctly to show she cares about their identity and culture. But, she said, it’s not always easy.

“I’m always intimidated (when reading the roster). So when I get to a name that I don’t know, instead of mispronouncing it, I create my own pronunciation key,” Pace said. ”For (the name Vaishu, for example), I would’ve written ‘V’, ‘i’ with a long ‘i’ (mark), and I would write the word ‘shoe.’”

But not all teachers do the same. Tadikonda said she has encountered many challenges with teachers mispronouncing her name.

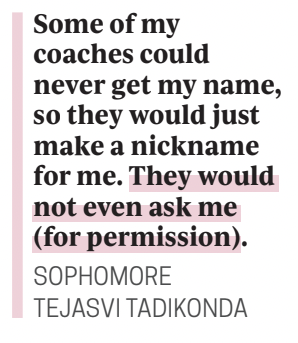

“Some of my coaches could never get my name, so they would just make a nickname for me. They would not even ask me (for permission). They would be like, ‘I’m just going to call you this so it’s easier for me,’” Tadikonda said. “I feel like I’m being given a number, and I am that number. Like, I’m not my name.”

For Dulay, she said she feels curious about how teachers will mispronounce her name on the first day of school.

“I really find it funny to hear how people pronounce my name,” Dulay said. “Like I don’t know how people can mess (my name) up, so I just sometimes get excited to see what (teachers) are going to do with it.”

Casso said problems with mispronunciation occur outside of school as well.

“I was at Starbucks and I said my name three times to the person who was serving me, and they said Lord-AY every single time,” Casso said. “(In the end), I just kind of accepted it. I was like, ‘Ok, it’s close enough.’”

Ultimately, Tadikonda said people should make an effort to learn the correct pronunciation of someone’s name.

“When you say my name wrong multiple times it just looks like you really just don’t care (enough about me), and that’s a big red flag,” she said.

Ultimately, in light of Celebrate Your Name Week which begins on March 6, Wan said schools can be a space for students and teachers to learn and celebrate one another’s names.

“When an entire school community engages in learning about each other’s names and celebrating the diversity reflected in our names,” she said, “it sends a strong message that the school community values and embraces the rich language and cultural diversity that students bring to our schools.”

![What happened to theater etiquette? [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Entertainment-Perspective-Cover-1200x471.jpg)

![Review: “The Immortal Soul Salvage Yard:” A criminally underrated poetry collection [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/71cju6TvqmL._AC_UF10001000_QL80_.jpg)

![Review: "Dog Man" is Unapologetically Chaotic [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dogman-1200x700.jpg)

![Review: "Ne Zha 2": The WeChat family reunion I didn’t know I needed [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/unnamed-4.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)

Celeste T • Nov 2, 2023 at 12:39 am

How do you say “Tadikonda?”