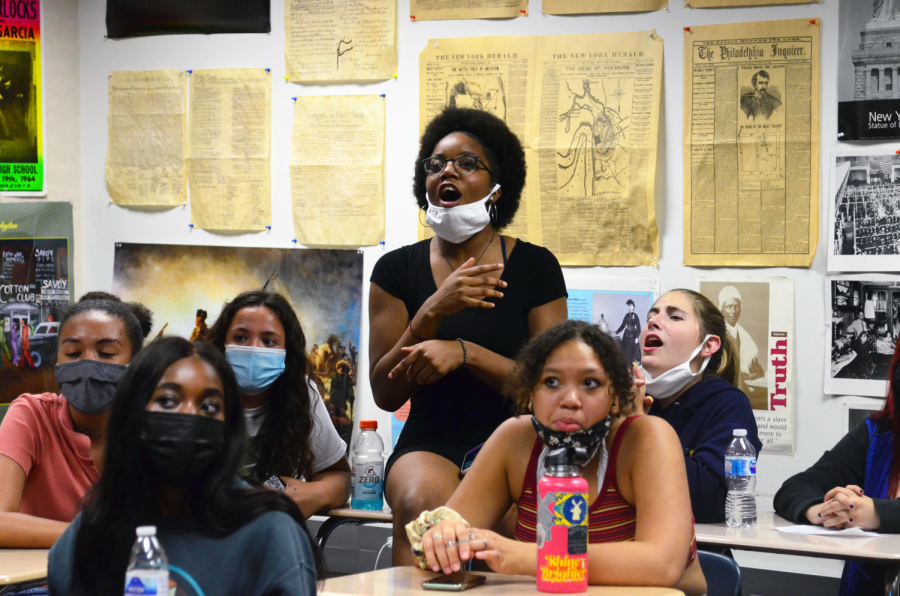

Vanessa Rasaki, co-President of the Black Student Alliance (BSA) and junior, has spent the past couple of months planning for Black History Month.

“(The BSA) met with the school administrators so that we could tell them how they can better amplify the school for Black History Month,” Rasaki said. “Usually (during) Black History Month, people talk about the bad things that happen, but we want this month to just show Black success and excellence.”

One important aspect of Black culture, Rasaki said, is African-American Vernacular

English, also known as AAVE.

“I think (AAVE) is a way for Black people to really connect with each other because it is

our own way of talking,” she said. “And I think it is something special to us culturally…Togetherness is what it means to me.”

Although AAVE has no exact definition, it is commonly considered to be the dialect of English that African-Americans speak. Stuart Davis, professor of linguistics at Indiana University, taught a class on AAVE, commonly known as Ebonics.

complexity

“From a linguistic perspective, Ebonics would be considered a dialect of English,” Davis said. “It would be called a social dialect as opposed to a geographical dialect…As a dialect of English, of course, it shares many of the same characteristics that other varieties of English and mainstream English (use), but like any dialect, it has its own sort of characteristics.”

CCS Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) Officer Terri Roberts-Leonard said AAVE is an integral part of African-American culture.

“I think it’s important to talk about in-group (and) out-group language,” Roberts-Leonard said. “There are certain words, phrases, ways of speaking that originated within groups (and) they kind of hold ownership of (it).”

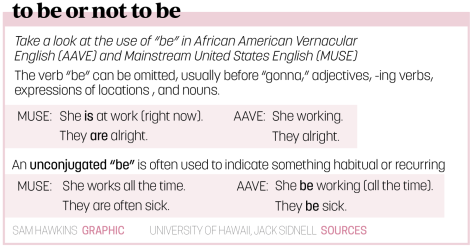

Davis said AAVE has linguistic complexity that sets it apart from other dialects of English. One example, he said, is the use of the word “be.”

“One of the patterns that you find in (AAVE) that you tend not to find in other varieties of English is the use of the word ‘be’ to mean something that’s regular or habitual,” Davis said. “So in AAVE, you can say something like, ‘They be going to the store.’ That does not mean, “They are going to the store,” it means, “They go to the store regularly.” So you can’t say something like, ‘They be going to the store just this one time;’ it doesn’t make sense… The use of what is called the habitual ‘be’ is a characteristic that’s pretty unique to African-American English.”

He also said some words differ in meaning, compared to standard English.

“People are aware that there’s a lot of slang, but there’s also a lot of words in African-American English, of course a lot of it’s just English, but usages that are not slang,” he said. “One interesting example is the use of the word ‘kitchen’ to mean the nape of the neck…And it’s not recognized by most speakers who are not African-American. But it’s a common term among African-Americans. It’s not slang; it’s never crossed over. (This) just shows the complexity of the language.”

stigma

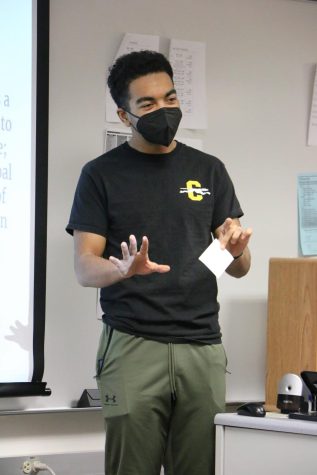

Despite the linguistic intricacies of AAVE, there is stigma against the dialect. Brandon Anderson, co-President of the African History and Culture Club (AHCC) and junior, said many people view AAVE as unprofessional or uneducated.

“It seems like those phrases (in AAVE), when they’re said exclusively by Black people, are seen as unintelligent,” Anderson said. “But then, when it becomes appropriated into the rest of English, suddenly that’s normal. It’s how people talk. It’s like, when Black people do it, there’s something wrong about it. But when other people start to do it, that’s when it becomes okay.”

“It seems like those phrases (in AAVE), when they’re said exclusively by Black people, are seen as unintelligent,” Anderson said. “But then, when it becomes appropriated into the rest of English, suddenly that’s normal. It’s how people talk. It’s like, when Black people do it, there’s something wrong about it. But when other people start to do it, that’s when it becomes okay.”

Davis said he agreed with Anderson, and said AAVE should not be scorned.

“African-American English should not be stigmatized,” Davis said. “It is a legitimate dialect and it has grammatical complexity. That’s underappreciated.”

Roberts-Leonard said people often subconsciously judge others based on their way of speaking.

“I think it’s important to remember that people shouldn’t judge people by language, and oftentimes they do,” she said. “That happens a whole lot so we have to really stop and ask ourselves: ‘Where do I get that from? Where along the lines did it come into my head that a person with a certain accent is less intelligent or less educated?’”

code-switching

To combat this stigma, many African-Americans have developed a subconscious way of adjusting their speech around different groups of people, commonly referred to as “code-switching.” Anderson said he has experience with code-switching.

“I sometimes, maybe, (code-switch),” he said, “but it’s lighter than I think other people (do). I think my entire family kind of talks ‘white,’ like my parents used to get made fun of when they were little for talking properly. And I think it’s weird that we say that it is talking ‘properly,’ but that’s my opinion.”

Rasaki said she believes everybody code-switches to a certain extent.

“When my mom is on the phone with one of my friends, she would be like ‘Oh my gosh, hi.’ and I’m like ‘Mom you don’t talk that way,’” she said. “I think (code-switching is) only negative when it starts to affect your personality or your actual self.”

Roberts-Leonard said African-American professionals often code-switch when they’re in the workplace.

“I think you would be hard pressed to find a whole lot of African-American professionals who don’t do some level of code-switching,” Roberts-Leonard said.

Roberts-Leonard said she does not actively code-switch, though she knows many African-American employees who do.

“I have a really good relationship with my supervisor, the Assistant Superintendent Tom Oestreich, so I’m able to bring a level of authenticity to work that some people don’t necessarily feel comfortable doing at other places or in other professions,” she said. “I have plenty of friends who have to majorly code-switch in order to maintain their employment just because, oftentimes, cultural differences are viewed negatively.”

Roberts-Leonard said she has often seen the atmosphere change based on a person’s ethnicity. Her own experience, she said, has shown her Black women are treated differently due to stereotypes in the workplace.

“I’ve been in situations where I’ve worked a lot with white women who are a lot more passionate or amped than I am but they’re never called aggressive, they’re never called sassy, they’re never accused of being upset when they’re not,” she said, referring to the “angry Black woman” stereotype. “All other things being equal with coworkers, they don’t get the same response.”

internet slang

Although African-Americans face stigma due to AAVE, many words and phrases such as “You go, girl” and “Periodt” have crossed over into mainstream English.

Rasaki said she often sees people that aren’t African-American use AAVE.

“As long as (people of other ethnicities) are respectful and know the meaning behind it, (it’s fine),” Rasaki said. “Because sometimes people can say something and mean it in a different way. But if it’s just regular slang, I think it’s okay. Just be respectful about it and don’t be a jerk.”

Davis said he has also seen how the slang components of AAVE move into standard English.

Davis said he has also seen how the slang components of AAVE move into standard English.

“The slang component of (AAVE) often crosses over into the wider society,” Davis said. “Even adults will say something like, ‘What’s up,’ (which is) originally an African-American expression. ‘You go, girl,’ that’s another expression that comes from the African-American community that’s crossed over so even mainstream Americans will say ‘You go, girl.’”

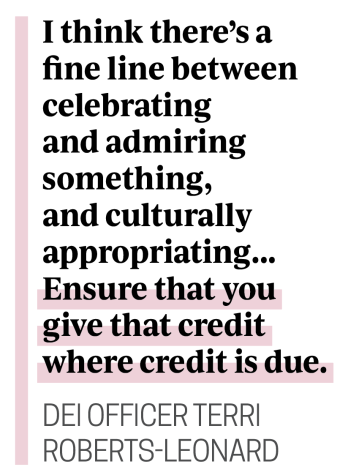

Roberts-Leonard said she believes AAVE faces cultural appropriation, which is the unacknowledged adoption of customs and practices.

“I think there’s a fine line between celebrating and admiring (something), and culturally appropriating,” she said. “A distinction within that is ensuring that you give that credit where credit is due. You’re not claiming something as something that you made up, or you brought to light…There’s nothing new under the sun. Many times what current pop culture thinks is new, is something that originated way, way back (from) people who they didn’t think it originated with.”

Anderson said he has complicated ideas about appropriation. He said although he appreciates a certain level of cultural appreciation, he sometimes feels the uniqueness of AAVE fades away as it becomes more integrated into modern slang.

Anderson said he has complicated ideas about appropriation. He said although he appreciates a certain level of cultural appreciation, he sometimes feels the uniqueness of AAVE fades away as it becomes more integrated into modern slang.

“On the one hand, it definitely is nice to see how a lot of other people will take on your culture…(and) try to use (language) in the way that you use it,” Anderson said. “But I also sometimes feel it almost takes something away, where (the words) are no longer a unique thing, and it’s something that everyone does.”

Rasaki said there are certain words from AAVE she believes should never be adopted by non-Black people.

“Like if a white boy uses the n-word, that’s a big no,” she said. “I’ve been called the n-word by so many people at school. So I believe there’s a line that shouldn’t be crossed.”

Roberts-Leonard said although many words and phrases from AAVE may be unknown or not used in mainstream English, different dialects encourage cultural diversity.

“I think it’s important to remember that groups have in-group language,” she said, “and that’s okay.”

![What happened to theater etiquette? [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Entertainment-Perspective-Cover-1200x471.jpg)

![Review: “The Immortal Soul Salvage Yard:” A criminally underrated poetry collection [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/71cju6TvqmL._AC_UF10001000_QL80_.jpg)

![Review: "Dog Man" is Unapologetically Chaotic [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dogman-1200x700.jpg)

![Review: "Ne Zha 2": The WeChat family reunion I didn’t know I needed [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/unnamed-4.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)