Last year, senior Elise Varhan had a choice to make. As an IB student, she needed to complete a science credit. Instead of going with the traditional branches of science, she decided to take an environmental science class.

“I decided to take IB Environmental Systems and Societies because I feel very protective of the Earth,” Varhan said. “Any kind of environmental science, I knew, was something that I wanted to explore. And in addition to that, the other two options I had were (IB) Physics and Biology, and I feel like environmental systems is a good application of both of those…and it kind of provides context for everything that I do learn. Like, it’s related to my own life and my own world.”

However, though Varhan has been able to take environmental science, historically, many other students have been unable to get an in-depth education about climate and environmental issues in school. But that may change soon. According to the Indiana Department of Education (IDOE), new state standards that require more climate and environmental science requirements in science classes will go into effect during the 2023-24 school year. Brandy Yost, IB Environmental Systems and Societies teacher, said she believes this is a good step.

“Climate education—in my perspective and what I’ve done over the years—is trying to present facts to students based on data that has been collected,” she said. “I feel like once students understand the facts, and it’s not just, ‘He says, she says,’ they are more open-minded to (the facts).”

Yost said the IB Environmental Systems and Societies course focuses on the social impacts of climate change as well as the science causing it.

“With my particular course, we look at (the) effects on people. So, it is a social studies course as well as a science course,” Yost said. “We not only look at the science but how people are affected, the differences between different countries…I think just having that human effect and seeing how humans are affected really hit home to a lot of my students where they feel more responsible to potentially do something more about it.”

Junior Ashlyn Walker, who is in Yost’s class, said she appreciates learning about the human impact and wished more classes talked about climate change and the environment outside of science courses.

“It’s super important,” Walker said, “(to be) implementing climate education within other classes besides science classes. Like my own French class, we were talking about the World Cup recently and how the World Cup impacts the environment with all of the emissions from traveling and expenses like that. I thought (that) was super cool.”

Yost said she agrees with Walker. In line with the broad impact of climate change, Yost said her goal in teaching climate and environmental issues is to empower students with the knowledge to make changes in their own lives.

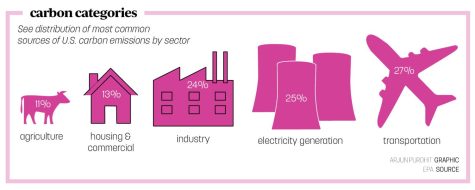

“My hope is that they will get involved in some way, even if it’s just making small changes themselves,” Yost said. “That’s something we talk about (in all of my classes), we look at their own carbon footprint, and talk about simple solutions that they can do. I talk about it more in my IB class, where we talk more (about) policy and how they can get involved to make changes like that.”

Varhan said the class has allowed her to make some of these small changes.

“I feel like the first place to start with change is education,” Varhan said. “(The course) has made me think a lot more about my water usage, mainly, as well as simple ways to do my own part in protecting the environment…(We learned about) daily usage in terms of bathroom use and dishwashing use and clothing use. I’ve kind of learned to put off my own convenience in order for what’s more appropriate to use more water for.”

Though Varhan said climate education has allowed her to live more sustainably, she said she has learned that it is not the sole solution.

“You can care about the environment as much as you want, but (the politicians) are the people that you have to convince to make that change,” Varhan said. “It starts with policy. That’s what I would like to do one day, having a career that focuses on using policy and finding a compromise that benefits the environment and (provides) fiscal benefit as well.”

According to Yost, one of the aspects of climate education she focuses on that is not included in state standards is these solutions to environmental issues.

“I try to make sure that students understand that there can be solutions, so that it is not all gloom and doom, and that they can try to focus on what we can do now,” Yost said. “It wasn’t expected to teach solutions. I would think that teachers that do not have a passion about (this subject) would not be teaching that. And I think a lot of teachers have struggled with teaching about climate change or don’t know what to teach.”

Walker said she appreciates learning about the different techniques and methods to mitigate the effects of climate change. Walker, who is the co-executive director of Confront the Climate Crisis, said the course has allowed her education to her advocacy work.

“Confront the Climate Crisis is a statewide group,” Walker said. “In September of last year, we held a climate policy conference with experts from all over the state and legislators and we even invited a lot of student groups. So, my own (IB) Environmental Systems and Societies class attended as a field trip, which was just the coolest thing to me because I got to connect my outside-of-school work with my own class.”

Varhan, who attended the climate policy conference with the class, said she believes climate education should be more solutions-based.

“I think (climate education) is important because a lot of people have notions that either, ‘Oh, climate change isn’t real,’ or ‘It’s too far gone,’ but it’s really not. There’s a lot of solutions…The hardest thing is educating people on that and changing our minds,” Varhan said. “Education is the right place to start because once you understand that there is a way you can do it, it becomes more pressing that, ‘This is something I should be doing.’”

Yost said she agrees with Varhan. She said she has seen her students go off to volunteer with local tree-planting initiatives or even study environmental science in college.

She said, “That’s what gives me joy, as a teacher, that if I can just affect a handful of students in my lifetime, that’s going to make a difference. That’s the way I can really make a difference, is by educating them because I know they’re going to be the ones to drive this (movement). So, that’s my goal, is to share that (knowledge) with you all.”

No matter what people do with this knowledge, Walker said she believes climate education is crucial.

“I think (education) is the most vital thing in getting people informed about what’s going on in our world with climate change and global warming,” she said. “That (way), they can not only make changes in their own personal life—like, personal changes to be more sustainable—but also be an advocate for bigger change.”

![What happened to theater etiquette? [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Entertainment-Perspective-Cover-1200x471.jpg)

![Review: “The Immortal Soul Salvage Yard:” A criminally underrated poetry collection [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/71cju6TvqmL._AC_UF10001000_QL80_.jpg)

![Review: "Dog Man" is Unapologetically Chaotic [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dogman-1200x700.jpg)

![Review: "Ne Zha 2": The WeChat family reunion I didn’t know I needed [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/unnamed-4.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)