For almost 14 years, junior Emily Chan’s parents owned and operated a Chinese restaurant in Carmel. The restaurant was always like a second home to Emily; when she was in elementary school, she spent almost every day after school there, playing or finishing homework, and as she got older, she sometimes worked there on weekends.

Recently, however, Chan’s parents made the decision to sell the restaurant due to the physical and mental strain it put on the family.

“The restaurant in general is too much of a physical workload. Many of our dishes (were) handmade and made fresh, from the appetizers to the main courses,” Chan said. “Any argument that happens there…will come back home, and that alone creates a lot of stress. On top of all of that, finding employees also became difficult. Many don’t want to work in such a stressful and physical intensive environment.”

But in addition to the stress, Chan said she had no intention of taking over the restaurant in the future. And that, according to new research, is not unusual. Most locally-owned Chinese restaurants don’t get passed down from parent to child, and Chan said she thinks the reasons why her parents sold theirs may be the same reasons why the businesses aren’t staying in the families.

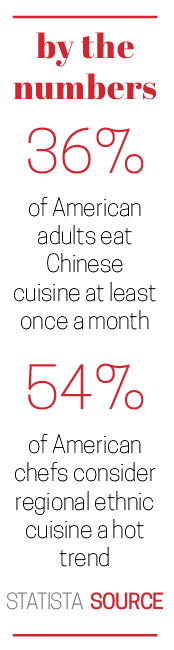

According to the United States Census Bureau, the most common field of work for first-generation Chinese immigrants like Chan’s parents is in the restaurant industry.

“It’s called the ‘cultural enclave,’” social studies teacher Michael O’Toole said. “So you’re looking for people, even though you’re looking in a new country, but if you don’t speak the language, or you have common religion, common interest (with others), it’s much easier…and (Chinese immigrants) had certain skills. They know that Chinese food is extremely popular in American culture, so they can open (a restaurant) up, (and) that way they can serve their community with actual traditional Chinese cuisine.”

Chan said when her mother first moved to New Jersey, she missed her home in China.

“When she was in a restaurant, like a Chinese restaurant, she (remembered) the food from back home,” Chan said. “It almost felt like home in a way.”

The Census Bureau also found that the most common self-employment for the children of immigrants is in computer services, followed by dentistry and the arts. In fact, restaurant work doesn’t even make the top five. Furthermore, data from Yelp shows that the overall number of Chinese restaurants in the United States has consistently declined in the past five years.

O’Toole said, “A couple things are happening there, either (the owners) are retiring, and their children have new educational opportunities and other ideas. (Or) because there were so many Chinese restaurants as well, it’s almost like a flooded market, so some of them will stay open, but some of them…should be shut down.”

Chan said she has seen this decline in Chinese restaurants firsthand.

“Many don’t want to work in such environments,” she said. “Along with that, many Chinese restaurants are family-based and have been passed down from generation to generation. But nowadays, the Chinese children that grew up in restaurants, at least the ones that I know of, pursued different careers.”

Junior Ben Lin’s parents have owned the Japanese restaurant Wild Ginger on 116th since they moved to Carmel in 2015. Lin may exemplify what Chan said she feels is the reason for the decline of Chinese-owned restaurants. He said he doesn’t spend much time at the restaurant and does not plan to take it over when they retire: his interests lie in computer sciences, and he knows that running a restaurant can be physically demanding and time consuming. Sometimes, he said, his mom comes home around 11 p.m.

Lin said the fundamental Chinese values of his parents were taught to him during his childhood.

“What they were taught culturally, when they were younger, they passed down to me and my sister,” Lin said.

However, the opportunities available to Lin and the interests he has developed are different from his parents’, and he will walk a different career path.

Chan said operating restaurants was one of the few opportunities available to Chinese immigrants coming to the United States, but that may not be the case for their children.

“(More) often than not, many (Chinese immigrants) didn’t speak much English and missed home, so the ‘perfect’ place would be a Chinese restaurant,” Chan said, “but now, to many Chinese immigrants or Chinese-Americans, opportunities are endless and so are careers; you just have to work hard for them.”

![What happened to theater etiquette? [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Entertainment-Perspective-Cover-1200x471.jpg)

![Review: “The Immortal Soul Salvage Yard:” A criminally underrated poetry collection [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/71cju6TvqmL._AC_UF10001000_QL80_.jpg)

![Review: "Dog Man" is Unapologetically Chaotic [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dogman-1200x700.jpg)

![Review: "Ne Zha 2": The WeChat family reunion I didn’t know I needed [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/unnamed-4.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)