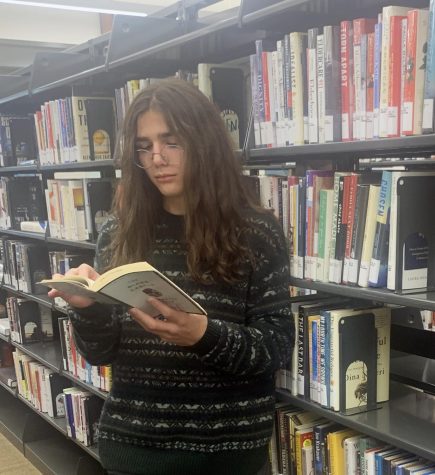

Senior Shannon Larkey said she was reading a book for her English class when the teacher asked students to pass the book to the front of the classroom.

Larkey said, “We were reading Homegoing last year in English. It follows the stories of these two African-American girls. One of them becomes a slave; one of them doesn’t. It follows their ancestry going into 19th century America, so (it showed) kind of the effects of slavery on families. I think (it’s) a topic that isn’t really talked about so I was really excited to kind of read a book about it.

“I remember we read the first chapter. We were going back (to) class and going to do an assignment about it (when) the teacher said, ‘Pass your books up to the front of the class,’” Larkey added. “We all started asking them questions, like, ‘Why are you taking this book away from us? What are we going to read instead?’”

Larkey’s experience represents the growing movement to censor books. On Feb. 15, the Indiana Senate Judiciary Committee passed a bill, which would allow prosecutors to criminalize K-12 school librarians for exposing harmful material to minors. The bill also prevents teachers and librarians from using “educational purpose” as a criminal defense. The full Senate reconvened on Feb. 27 to discuss the bill; amendments to the bill are ongoing.

Moreover, the movement to censor books is not limited to Indiana. According to the American Library Association, there were 781 attempts to ban books across the nation in 2022, the highest number of attempted bans since the organization began compiling these numbers.

Our School’s Policy

Terri Ramos, department chairperson for media and communications, said attempts to ban books have occurred at this school as well. No book; however, has been banned.

According to Ramos, parents can fill out a form to challenge a book. The form will then go to Ramos, the principal, the director of curriculum, instruction and assessment at the school district, and the superintendent. Then, they will make a decision as to whether the book should be removed from the media center.

What happens more often, Ramos said, is a student will check out a different book if their parent has a concern.

“I’ve been a librarian since 2003 and in all those years I’ve had maybe one discussion,” Ramos said. “A book went home. (The parent) saw a particular word she didn’t like, so she said, ‘I don’t want my son to read this,’ and I was like, ‘Ok,’ and that’s all she wanted. The book came back and he picked a different one.”

Content Concerns

Ramos said many books that are banned or challenged contain racial, sexual and/or LGBTQ+ content.

“A lot of it centers around race, LGBTQ+, and some people will even say farting, you know, or there’s a curse word, like ‘damn’ or ‘butt,’” Ramos said. “So, for example, Walter the Farting Dog…was challenged but retained on the library shelves of the West Salem Wisconsin Elementary School despite the book’s use of the words ‘fart’ and ‘farting’ 24 times. In more serious manners, it may have something to do with what people consider to be sexually explicit passages.”

Larkey said our school replaced Homegoing with a different book due to the description of a rape scene.

She said, “It was kind of disheartening because all of us were excited to read it and they (replaced) it because there was a detailed rape scene. We could’ve skipped over that scene in class and not just done anything on it and just read the rest of the book.”

Assistant Principal Valerie Piehl and English teacher Jacleen Joiner declined to comment on reasons for Homegoing’s removal. However, Piehl said Homegoing has not been banned.

For junior Amanda Pan’s part, she said these books should stay in schools.

“A lot of more conservative schools will remove books that have a trans main character or if they promote (critical race theory),” she said. “Obviously, I don’t think you should ban any of those because it gives an insight on communities that you (may) not be a part of and it’s more inclusive.”

Age and Maturity

Still, despite those arguments, Michael Fortuna, sophomore and volunteer at our school’s media center, said people must also consider the extremity of content portrayed since most high school students are minors.

Fortuna said, “It’s hard to draw a very definitive line (about what should be censored) because of the subjective nature of literature, but I think if there is extreme sexual content—whether it be heterosexual or homosexual—(then the book should be banned). I know I’ve read quite a few books in this library that have that extreme either sexual or racial content, and I’ve certainly come across a few that I think probably aren’t for the high school audience.”

On the other hand, Pan said the idea of censorship should apply more to younger students rather than high school students.

“For some books, like To Kill a Mockingbird because of the language used in the book, I don’t think it should be in elementary schools because elementary schoolers are so impressionable that they might go around and be using those kinds of languages and those kinds of ideals,” she said. “But I think at a certain point, like in high school, people are old enough to realize that these books were written in different time settings and you shouldn’t be pursuing the ideals of those books.”

Moreover, Ramos said the media center is a library for everyone, including 18-year-old students and staff members.

Ramos said, “I have a lot of 18-year-olds out here (in the media center). I think when I looked mid-year last year, there were about 600 kids that were 18 years old. They can read whatever they want. I also have adults in the building that I buy for who are teachers—teachers, staff members, etc. who read books from this library.”

Classroom Curriculum vs. Media Center

In addition to the difference in banning books between ages, Ramos said there is also a difference between censoring books for the classroom curriculum and media center.

“The thing about a school library is this is choice. There’s nobody here requiring you to read anything we have here—any ideas,” she said. “In a classroom, when the teacher says, ‘We’re all going to read this,’ then yes, now (students) have to read it…Any parent at any point can say, ‘I don’t want my child to read that’, and we can assign a (similar) book to that child and still do the same activities.”

Larkey said the line for censorship in assigned books should depend on how teachers use the books in class.

“I’m a GKOM, so I saw my freshman reading (The Glass Castle) so I decided to read it. I don’t know what their teachers are doing with the books, but I think you could definitely get some really, really good lessons out of those types of books,” she said. “If the lessons are good and the book teaches a good lesson that can be applied outside of school, then we should keep the book.”

For that reason, Fortuna said the criteria for choosing books for the classroom curriculum can be more flexible.

Fortuna said, “The interpretations (of books) can often be guided, and having an open platform to discuss potentially more adult topics allows for the book’s meaning to not be lost or misunderstood, which could be the case if the student had read the book on their own.

“In AP (English) Literature and Composition, a book (we) read is called The Nickel Boys,” Fortuna added. “There are strong depictions of racism and inequality, as well as scenes where child rape is implied. However, the book has incredible themes of hope, friendship and endurance as well. If those scenes weren’t discussed and dissected, then (students) would be left (with) a frightening apparition. Instead—while still frightening—(those scenes) add meaning and enhance the novel’s central themes.”

Impact on Students

In any case, Ramos said it is important to recognize that banning books prevents students from accessing information.

Ramos said, “I would say first and foremost that the banning of books prevents the acquisition of knowledge. It is 100% what I am against because every human being has the right to access information of all sorts.

“When you’re looking at a high school library where you have all these different grades and parents who feel different ways on different topics and all of those things, like, how do you distinguish (between what books should and shouldn’t be banned), you know?” she added. “If you start cutting one (book), then you have to cut this one, and then this one, and then this one, and then what’s left? Like, nothing.”

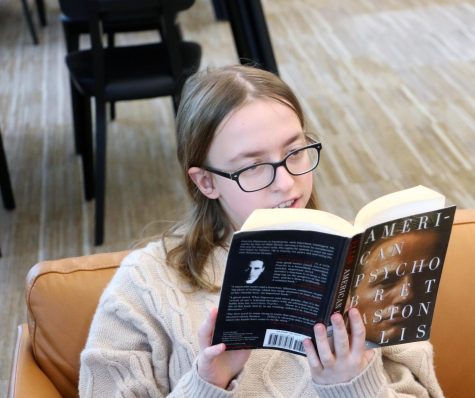

Along those lines, Pan said banning books restricts students from reading about important social issues.

“I read American Psycho and that book was so insane,” she said. “There were certain moments where I genuinely had to stop and take a lap around the house. The guy would be talking about stabbing some homeless person on the street or he’d be talking about feeding a cat to the ATM. Obviously, that’s the main point of the book (to read those scenes) and I think you need to read those types of books to get the message.”

But finding that line, Fortuna said, can be difficult.

Fortuna said, “It’s hard because in some books, it’s just pure sex for sex, but other times it serves to underscore literary topics or for allegories and in those cases, it is necessary for the text as a whole.

“(For example), in the 2010s, Looking for Alaska was challenged (on a) very broad scale across U.S. libraries because there is a scene in which two teenagers partake in oral sex,” Fortuna added. “The scene in which they do partake in oral sex is written in very medical, very formal language. The following scene is just a kiss between the two characters and that’s written in (a) very informal, very warm language, and it serves to provide contrast and show that connection isn’t solely based on sexual intimacy.”

Impact on School Librarians

Ramos said the controversy around banning books did not change the types of books she bought for students.

“I didn’t shy away from (purchasing) a book that has a character (who is) LGBTQ, or Asian, or Black, or Hispanic or whatever (just because somebody challenged similar books),” Ramos said. “It made us really look at, ‘Oh my gosh, are we really hitting all of these groups and making sure everybody’s represented?’ It’s about getting books in kids’ hands so they can see themselves so that they can face difficult situations, and so they can have information on how to make decisions that are best for them.”

At the same time, however, Ramos said the new legislation has impacted her emotionally.

“(The bill) doesn’t change my job,” she said. “Am I very careful about the types of books? I don’t know that I am any more careful than I ever was, but I know that (the bill is) out there—that somebody could take what I do and construe it as immoral or pornographic. It makes me feel terrible. I’ve spent the majority of my life working with teenagers; they’re at the core of everything that I do. I would not intentionally try to hurt any child. For somebody to tell me that I’m being immoral or providing pornographic material is gut-wrenching.”

The Right to Read

Ultimately, Larkey said she believes all students should have the right to read whatever they want.

“If you want to read the books, read the books. If you don’t want to read the books, then don’t read the books,” she said. “We have freedom of press, freedom of speech, (so) why not freedom over what we read?”

As a parent herself, Ramos said other parents should not get to decide what her children can read.

“Nobody has the right to decide for somebody else what they should read, right? I have two students in this school system. Nobody else gets to say for my kids what my kids read. That’s the problem I have (with banning books),” Ramos said. “(Students are people.) They have their own rights to an extent.”

In light of National Library Lovers Month in February, Ramos said everyone should have the freedom to choose what information they access.

“We had a Bronze Age and we had a Stone Age, and we are now squarely in the middle of the Information Age,” she said. “Information and text and all of these resources we have—it is the crux of our very democracy that everybody gets to choose their own information. If you remove that (freedom), you remove a basic tenet of who we are as Americans…I hope my role here is clear that literacy is crucial and that all students should honor and protect their right to read—all the time, every day.”

![What happened to theater etiquette? [opinion]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Entertainment-Perspective-Cover-1200x471.jpg)

![Review: “The Immortal Soul Salvage Yard:” A criminally underrated poetry collection [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/71cju6TvqmL._AC_UF10001000_QL80_.jpg)

![Review: "Dog Man" is Unapologetically Chaotic [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dogman-1200x700.jpg)

![Review: "Ne Zha 2": The WeChat family reunion I didn’t know I needed [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/unnamed-4.png)

![Review in Print: Maripaz Villar brings a delightfully unique style to the world of WEBTOON [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/maripazcover-1200x960.jpg)

![Review: “The Sword of Kaigen” is a masterpiece [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-201051.png)

![Review: Gateron Oil Kings, great linear switches, okay price [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-200553.png)

![Review: “A Haunting in Venice” is a significant improvement from other Agatha Christie adaptations [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/e7ee2938a6d422669771bce6d8088521.jpg)

![Review: A Thanksgiving story from elementary school, still just as interesting [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-26-195514-987x1200.png)

![Review: "When I Fly Towards You", cute, uplifting youth drama [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/When-I-Fly-Towards-You-Chinese-drama.png)

![Postcards from Muse: Hawaii Travel Diary [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/My-project-1-1200x1200.jpg)

![Review: "Ladybug & Cat Noir: The Movie," departure from original show [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ladybug__Cat_Noir_-_The_Movie_poster.jpg)

![Review in Print: "Hidden Love" is the cute, uplifting drama everyone needs [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/hiddenlovecover-e1693597208225-1030x1200.png)

![Review in Print: "Heartstopper" is the heartwarming queer romance we all need [MUSE]](https://hilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/museheartstoppercover-1200x654.png)